| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

Archaeological excavation of a medieval city and presumed Nestorian Christian graveyard

Starting point

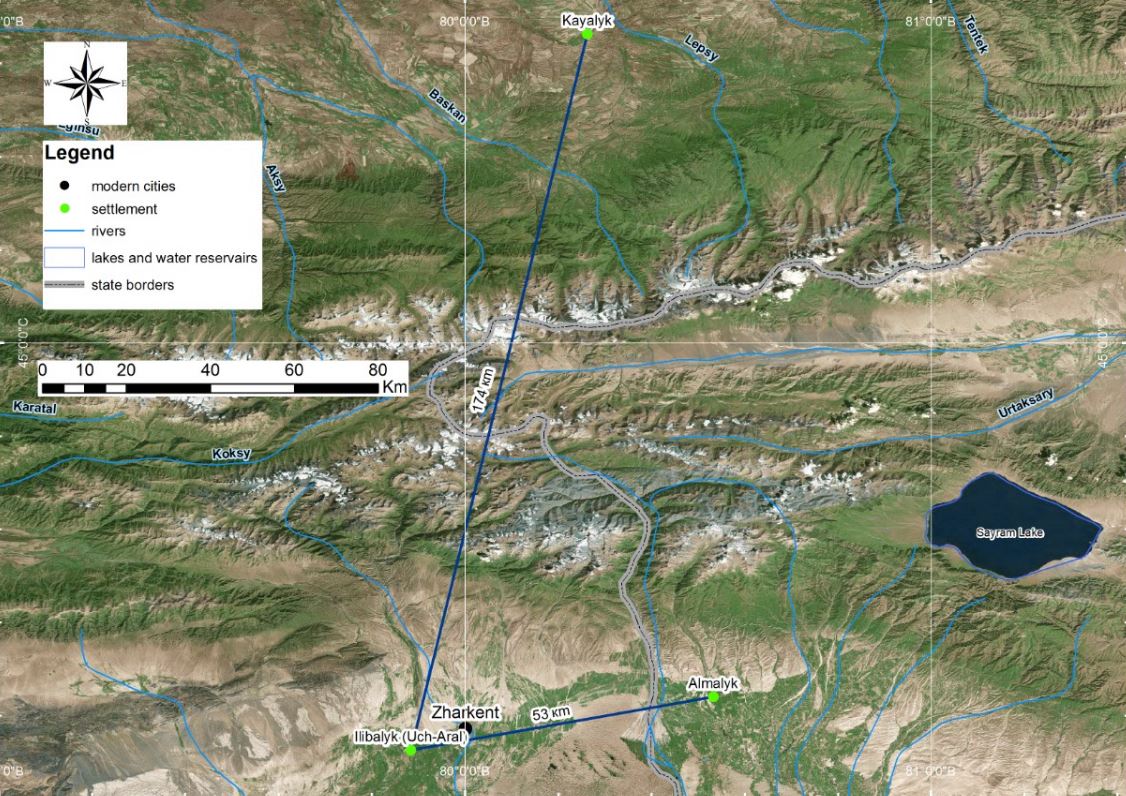

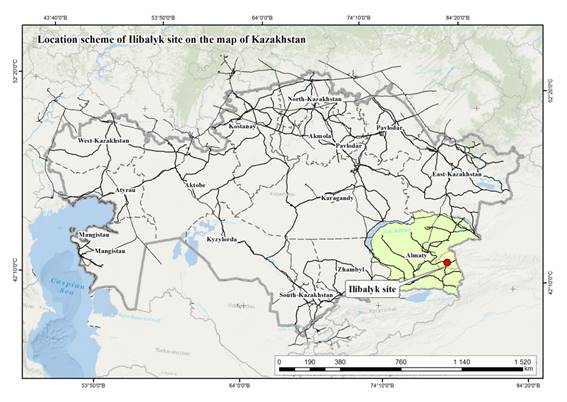

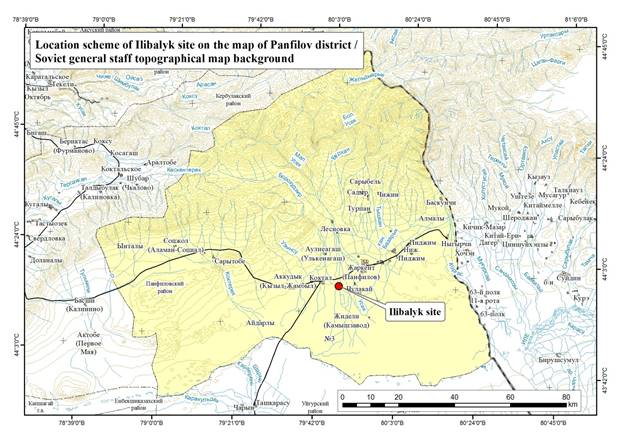

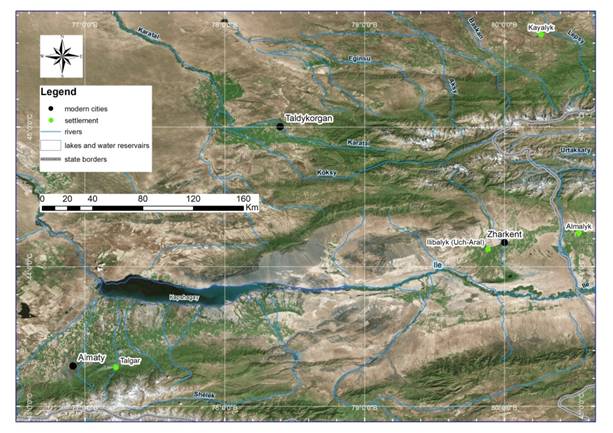

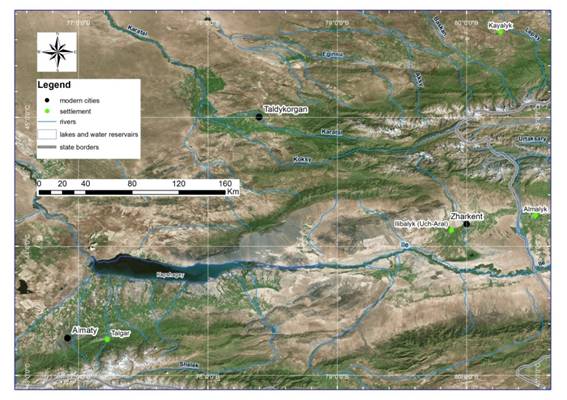

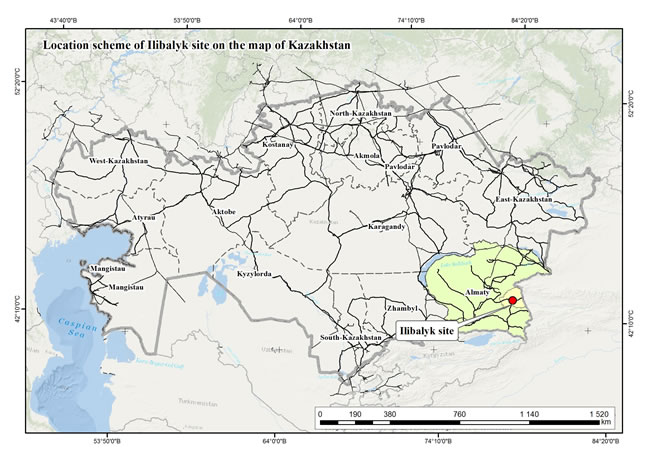

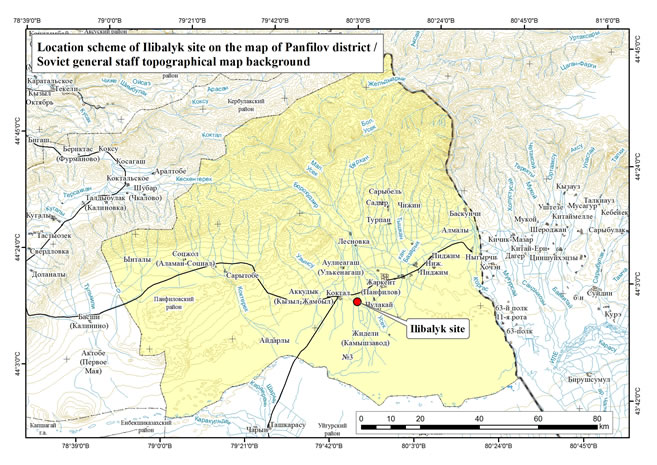

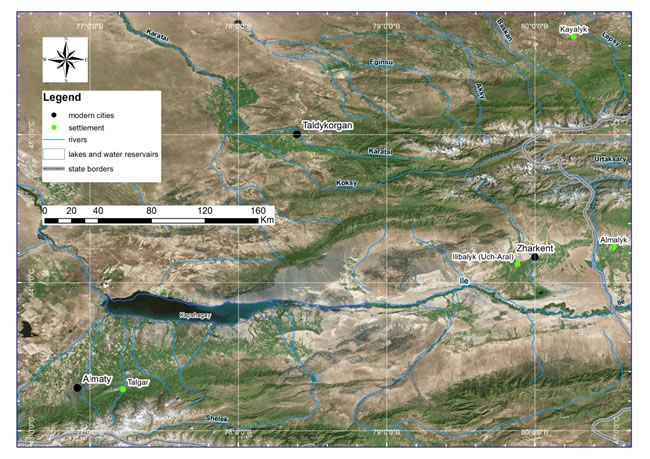

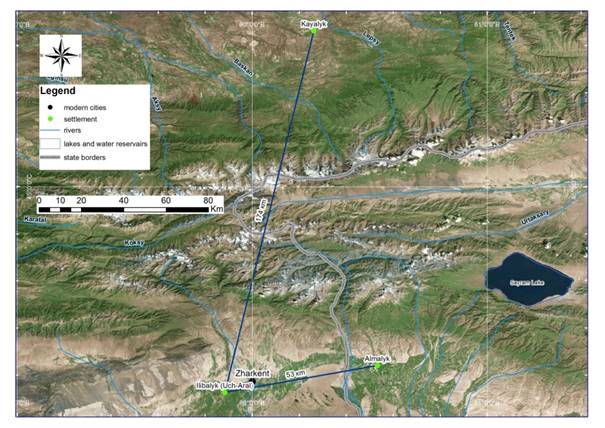

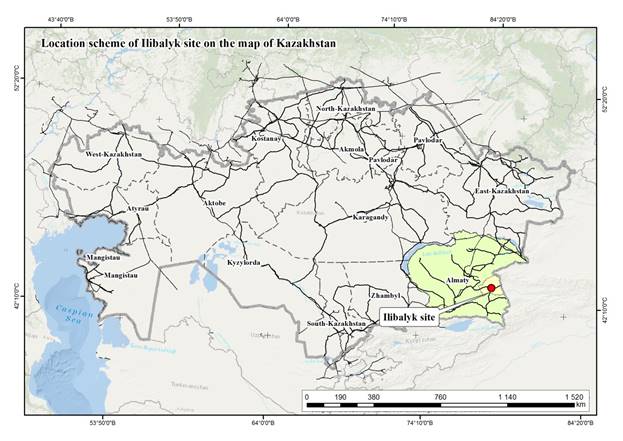

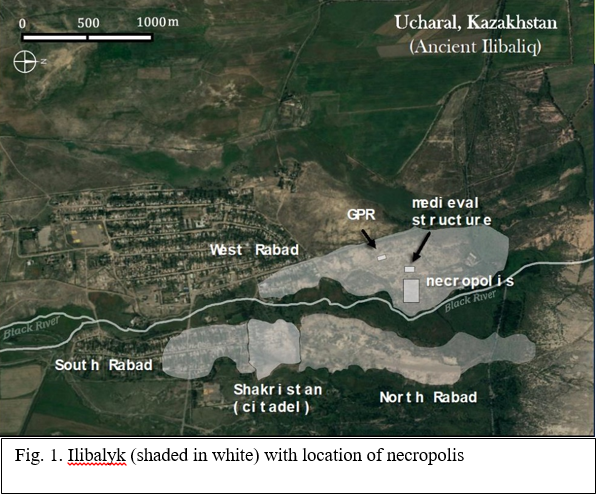

The present project includes topographical and archaeological studies of the large ancient settlement on the territory of the Ili River Valley – Uch-Aral, which is also known in Armenian, Persian and Chinese sources of XII-XIV centuries as Ilanbalyk – Ilibalyk – Ilibaly. The ancient settlement was situated on the left river-bank of the Ili River in a distance of two marches from the city of Almalyk which lies in today’s People’s Republic of China. (See map) A large amount of the coins found on the surface of the ancient settlement, and dating from the XI-XV centuries, reveal an intensive urban and commercial life of the city situated on the territory of the Tien-Shan Corridor of the Great Silk Road.

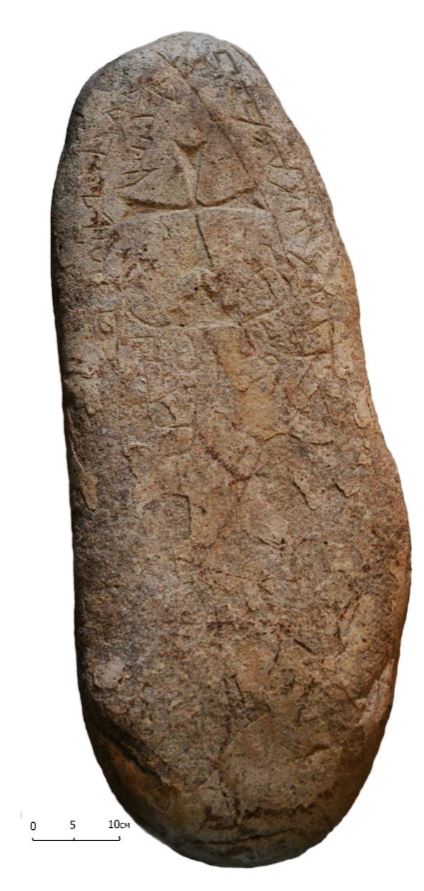

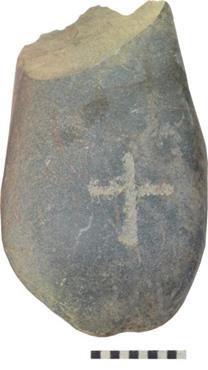

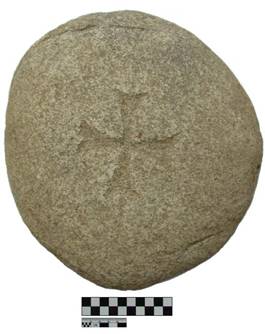

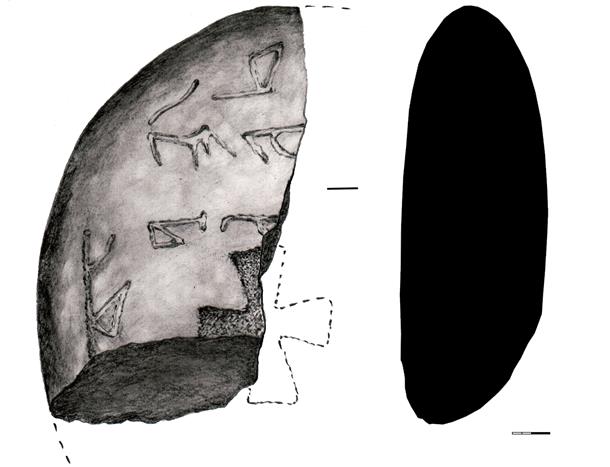

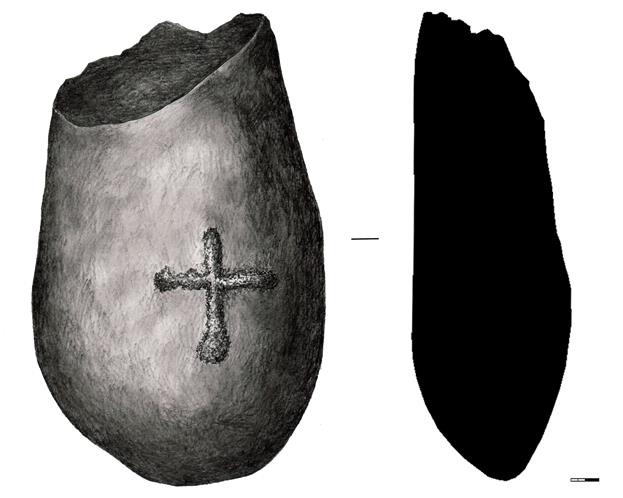

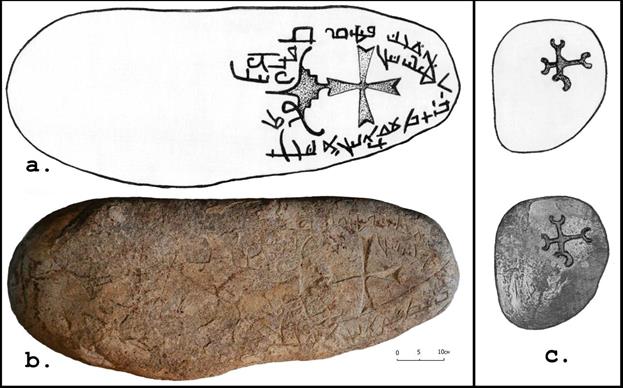

In 2014, a Nestorian gravestone (kayrak) was also found at Uch-Aral. The c. 100 cm long, undated gravestone has an engraved Maltese cross on the main long side and an inscription in Turkic language and Syriac script. The site of Ucharal is identical with ancient Ilan Balik, which was mentioned, next to Almalik and Taraz, by the Armenian Cilician king Hethum I when he returned in 1254 from his tribute-bringing journey to the Mongol Great Khan Möngke.

According to V.V. Bartold, the city was mentioned in Muslim sources shortly before the Mongol expansion. It was the capital of a ruler named Ozar (Buzar). Later the city voluntary surrendered to Genghis Khan. Ozar’s dynasty was ruling the city of Almalyk for two generation at least. It is known, that at that time there were 45 days of travel between Otrar and Almalyk and 2 weeks between Almalyk and Beshbalyk (the former capital of the Uyghur State in toda’s China).The Russian Orientalist from Saint-Petersburg N.N. Paustov visited Almalyk in 1902. In the city of Kuldzha he saw findings from Almalyk – two kayraks with crosses and inscriptions.

The discovery of a Nestorian kayrak on at Uch-Aral allows presuming that the ancient settlement of Uch-Aral are the ruins of the city of Ilanbalyk mentioned by Hethum I as the city near Almalyk.

Goals

1. Archaeological exploration of this medieval city (XI – beginning of XV centuries) on the Great Silk Road

2. Search for the assumed Nestorian graveyard and of further Christian heritage sites.

3. Investigation of ties with the city of Almalik and possibly also with the Catholic community residing there till the 1340s.

Partner in Kazakhstan

The Scientific & Research Organisation „Archaeological Expertise LLC", Almaty.

Leading project team

Prof. Dr. Karl Baipakov, Almaty ![]()

Dr. Dimitry Voyakin, Director Archaeological Expertise LLC, Almaty

_______________________________________________________________________________________

2016

Eurasia Exploration Society, Switzerland

Tandy Institute for Archaeology, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, USA

Archaeological Expertise LLP, Kazakhstan

Archaeological Society of Kazakhstan

Abbreviated Report for Internet

(report download here)

SCIENTIFIC FIELD REPORT

on

COMPLEX ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS

OF THE

USHARAL (ILIBALYK) SITE

Pottery sherd with incised cross in the hands of Steven Gilbert,

immediately after arrival from the excavation to the camp.

Usharal village, Kazakhstan

Almaty, 2016

Under supervision of:

Prof. Christoph Baumer

And

Prof. Karl Baipakov

Summary

The present project report includes topographical and archaeological studies of the large medieval settlement on the territory of the Ili River Valley – today’s Usharal, Kazakhstan, which is also known in Armenian, Persian and Chinese sources of 12th - 14th centuries as Ilibalyk, Ilibalyk, or Ilibaly. The ancient settlement was situated on the left river bank of the Ili River, a two-day march from the city of Almalyk, now located in northwest China. A large number of the coins, which were collected on the surface of the ancient settlement, demonstrate the significant urban and commercial life of the city from the 11th to the 13th centuries situated in the mountains of the Tien Shan corridor of the Great Silk Road.

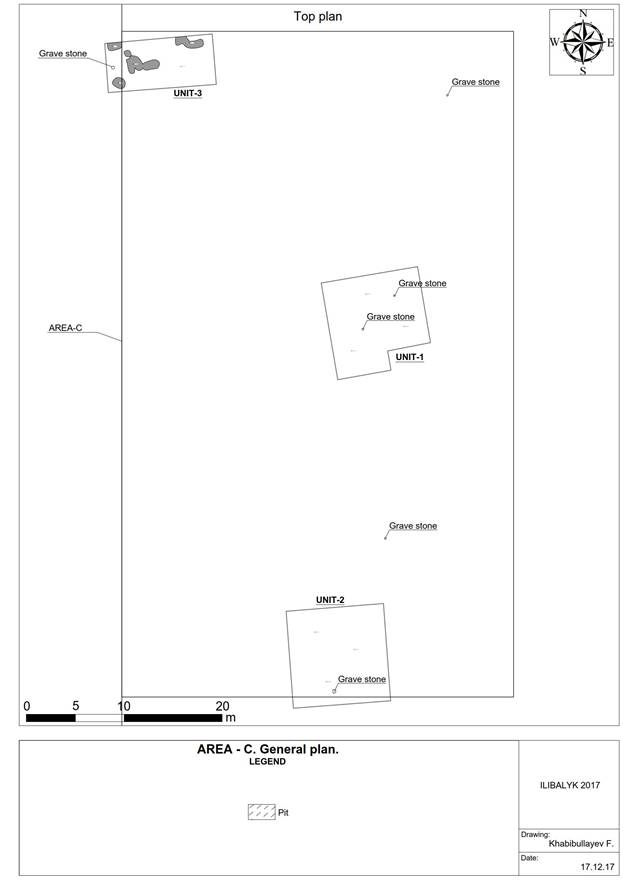

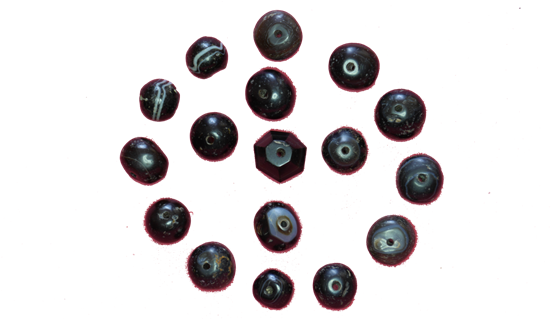

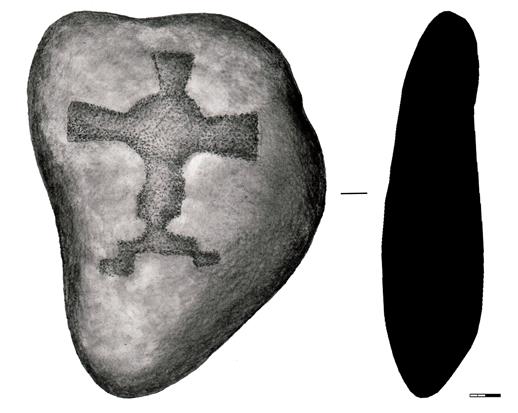

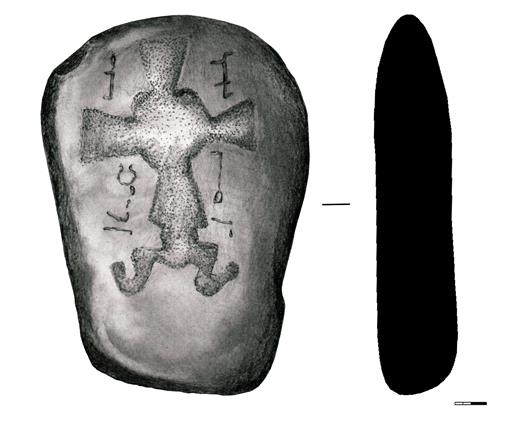

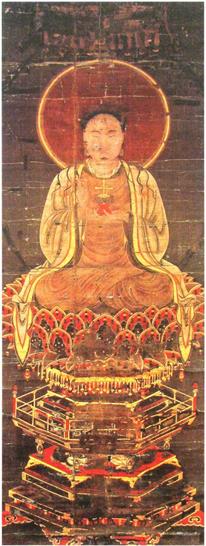

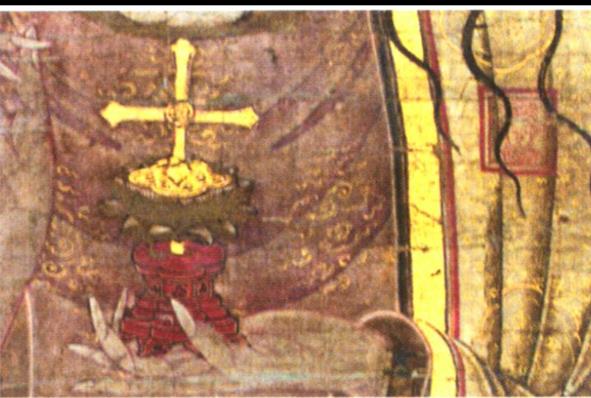

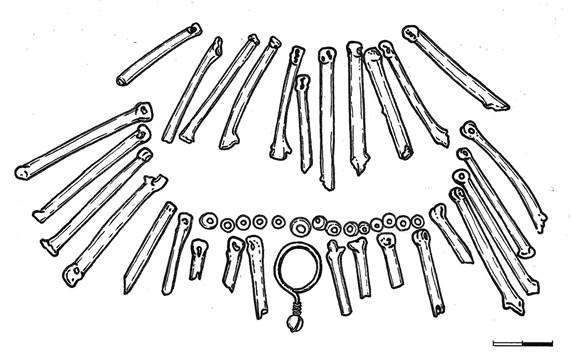

In addition, the discovery of gravestones, or "kayraks" with Nestorian crosses and Syriac or Old Turkic inscriptions demonstrates the presence of Christian communities, most likely Church of the East (commonly known as Nestorian) in the city.

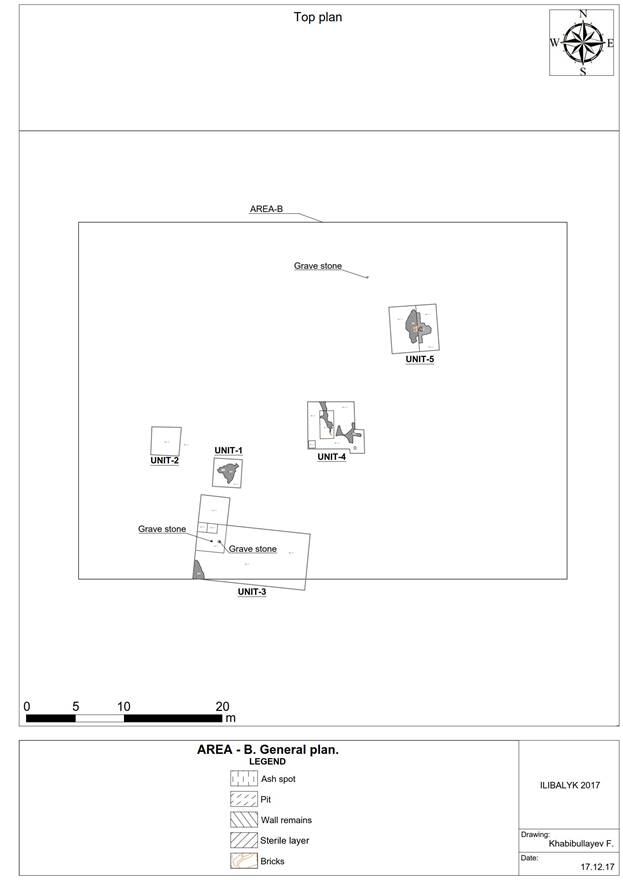

Our project includes a report on the excavation of the urban fortifications of the city; topographical studies of its territory; and an analysis of the house-building system and economy. It also includes the research of a potential Nestorian necropolis and remains of structures which could indicate a church and its ties with the city of Almalyk known for its community of Nestorian Christians and a 14th century Catholic mission.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1

General information about the project

Background

In 13th and 14th centuries numerous ambassadors, adventurers and spies from Western Europe traveled to Mongolia seeking protection and possible alliances as well as to develop various political and commercial contacts with the Mongolian Empire.

Among them there were the famous Venetian traveler Marco Polo, ambassadors of the Pope Innocent IV, the Franciscan monk Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, Frenchman Andrew of Longjumeau, Italian Ascelin of Lombardy, and William of Rubruck – an unofficial ambassador of French king Louis IX, as well as the King of Cilicia, Getum I.

The embassy headed by Getum I travelled to the territory of Möngke Khan in 1253. They were well received by Möngke Khan and obtained an agreement for a reduction of taxes. In 1254, Getum I returned. The description of his return is a well-described and important historical source. Among other things, it provided confirmation of the localities of such medieval cities as Almalyk and Taraz, which correspond to their modern locations.

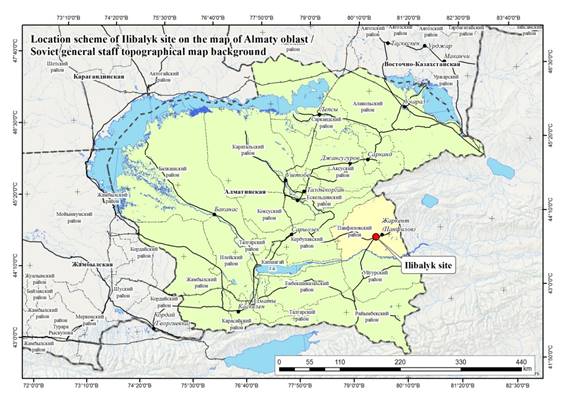

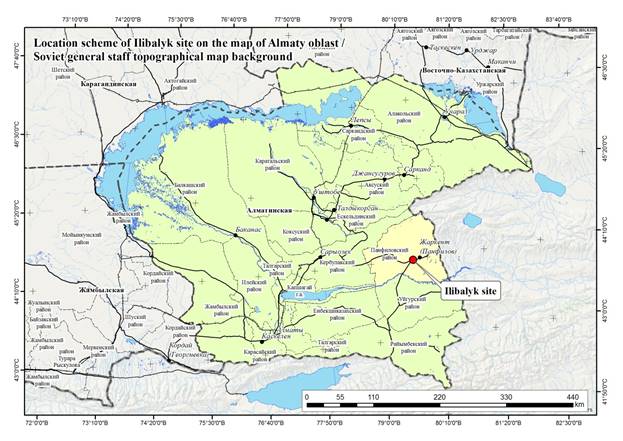

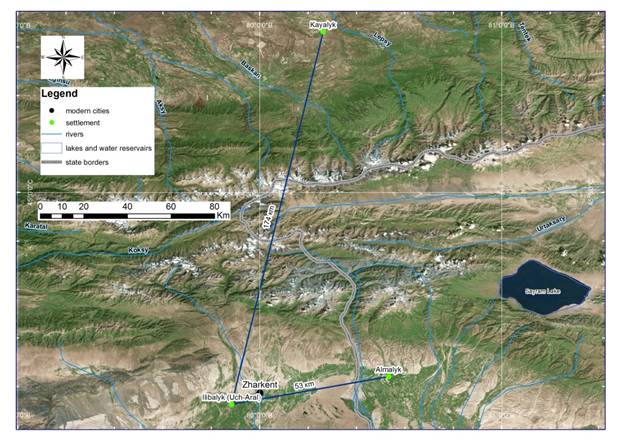

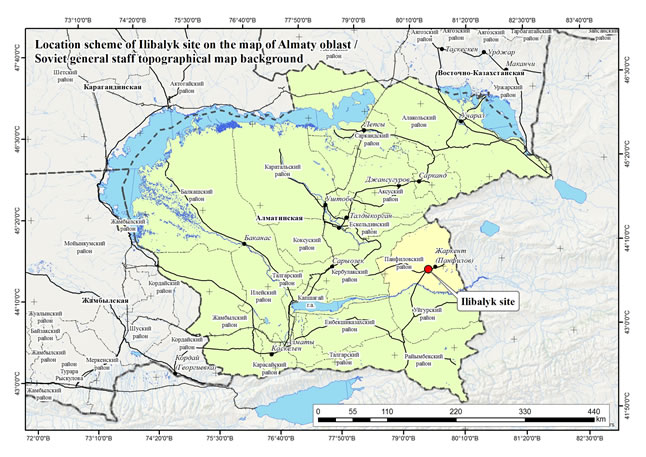

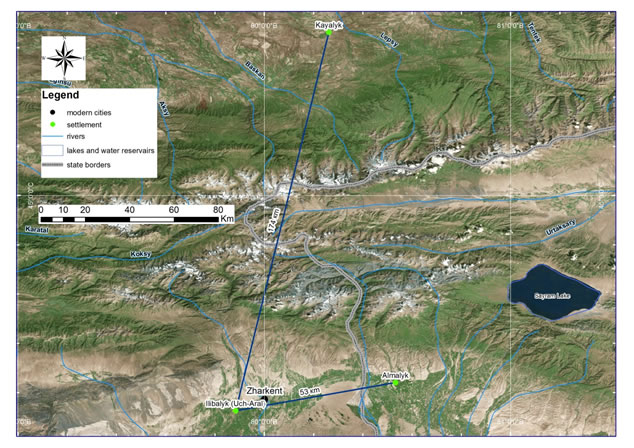

This historical source also mentions the city of Ilibalyk or Ilanbalekh (Ili-bali according to the Chinese sources). However, for a long period of time archeologists were unable to identify the exact location of this city. One theory advocates that the ancient city of Ilibalyk is situated between the modern villages of Koktal and Panfilov (now Zharkent) and potentially corresponds to the ancient settlement of Usharal [See the photo of the remains of the eastern wall on the territory of the site of Uch-Aral: Attachment 1]. Recent findings since 2014 provide more certainly that the ancient city of Ilanbalyk or Ilibalyk corresponds to the ancient settlement of Usharal [See the location of the ancient settlement of Ilibalyk/Uch-Aral in Attachments 2-3].

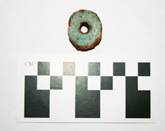

First, the rich collection of coins found on the territory of the ancient settlement demonstrates the importance of the city. In total three coin caches and another 123 singular coins have been found on the territory of the ancient settlement. All collections were mainly composed of Dirhams of 13th -13th centuries [See the publication on the coin discoveries and pictures of some of them in Attachments 4-11].

The above-mentioned numismatic findings reveal the active financial exchanges in the city during 13th through the first half of 14th centuries. They also show that the city existed in 11th century.

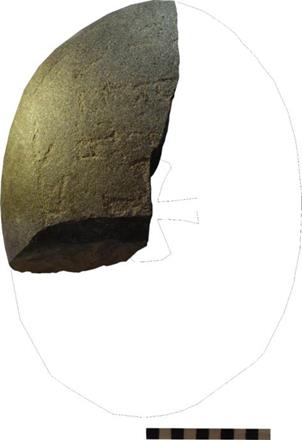

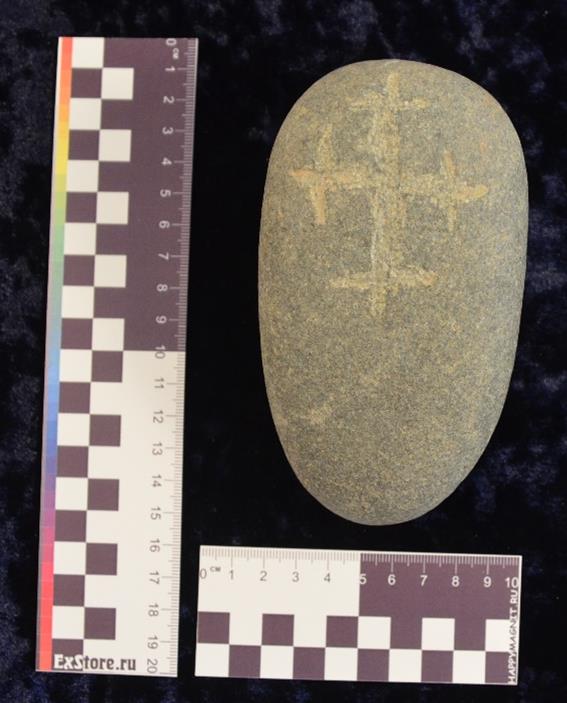

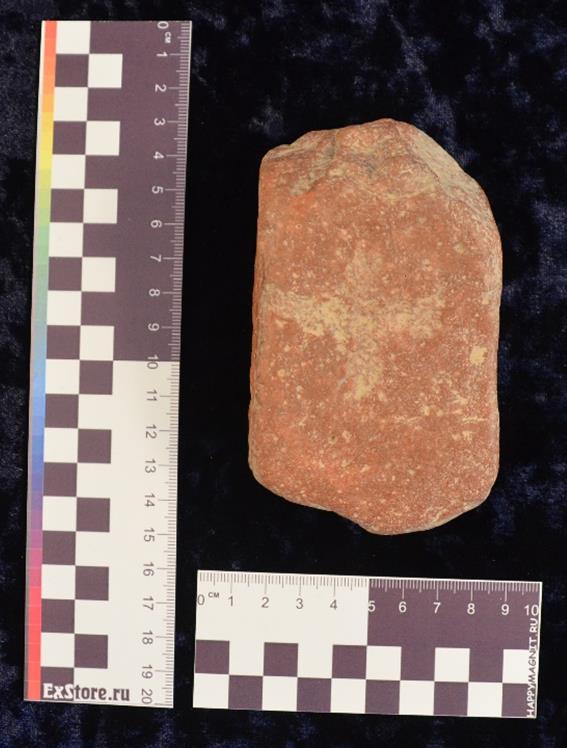

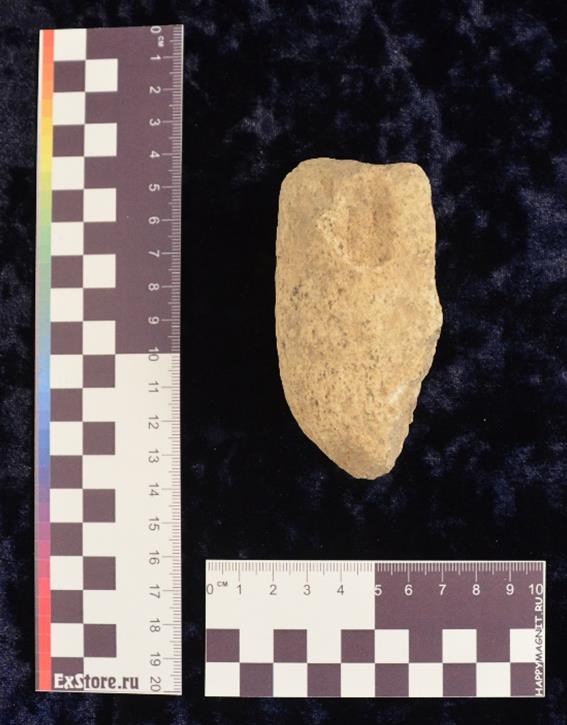

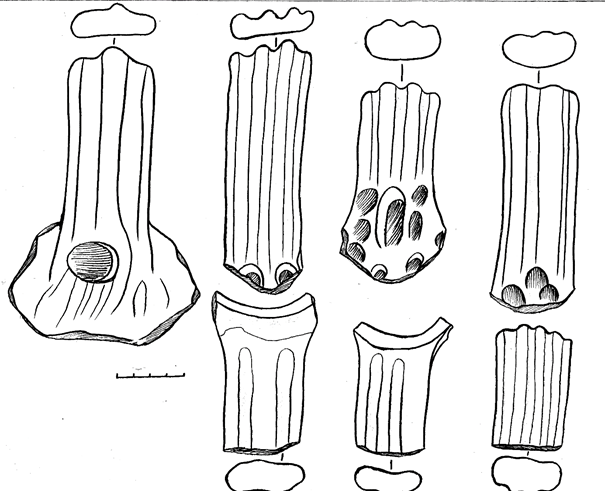

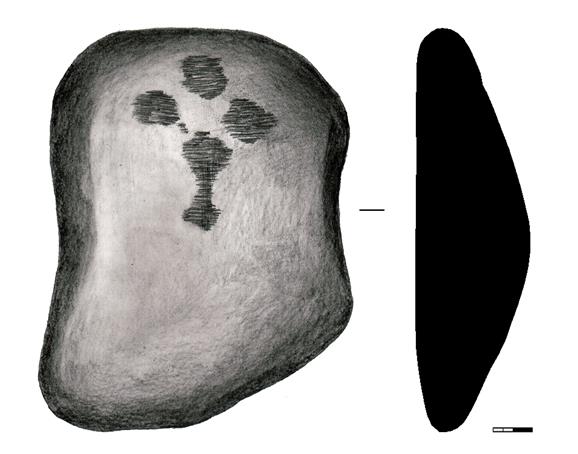

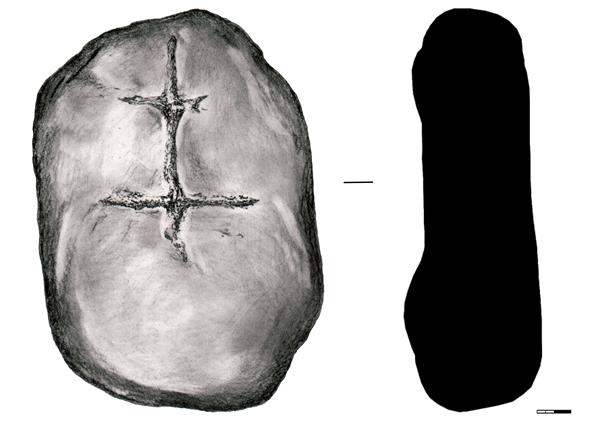

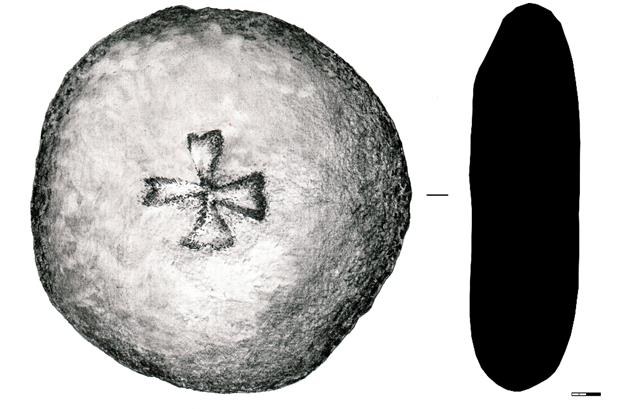

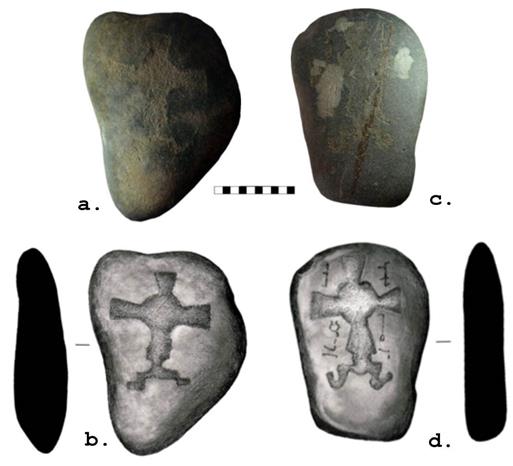

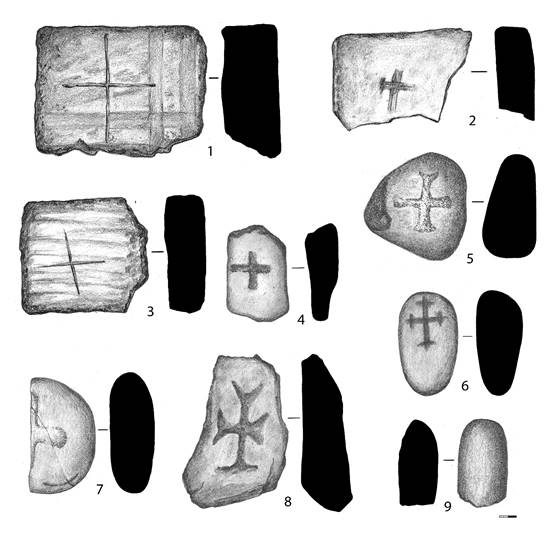

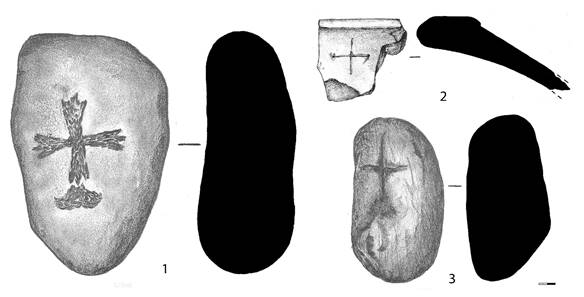

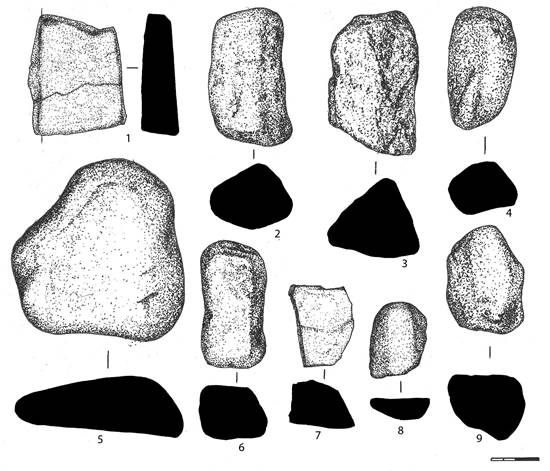

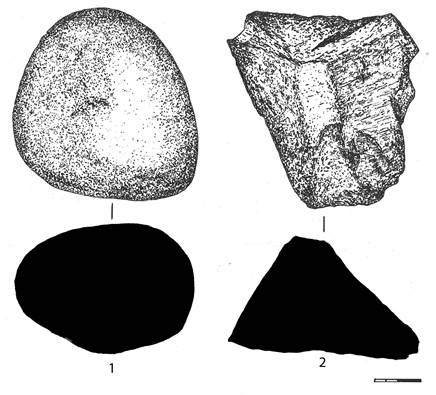

Second, the "kayraks" or gravestones with Nestorian-styled crosses along with two that contain inscriptions were found on the territory of the ancient settlement in the course of this project. The stones with inscriptions are yet to be translated. [See the photos of the kayraks in Attachments 12-16]. It is interesting to mention that Nestorian kayraks were also found on the territory of the neighboring city of Almalyk.

According to V.V. Bartold, Almalyk is mentioned in Muslim sources shortly before the Mongolian expansion . It was the capital of the ruler named Ozar (Buzar). Later the city voluntary surrendered to Genghis Khan. We know his dynasty ruled the city of Almalyk for at least two generations. The location of this city is clearly identified as being on the territory of the People’s Republic of China. Historical sources affirm that travel along the Silk Road took approximately 45 days between Otrar and Almalyk and 2 weeks between Almalyk and Bishbalyk (the capital of the Uyghur State).

As one of the main cities on the territory of Chagatai Khan, Almalyk became a main focus of mission efforts and a center of European missionaries as they spread Catholicism on the territory of the Mongol Empire. In the 1330s, under the rule of Dzhenkshi Khan the Catholics had established a church with a bishop in Almalyk. The Catholic influence ended abruptly during a severe persecution of Christians starting in 1339 or 1340 by Ali-Sultan.

In 1902, the Orientalist from Saint-Petersburg, N. N. Paustov, visited Almalyk. While in the city of Kuldzha (today's Ili) he observed two gravestones with crosses and inscriptions said to be from Almalyk. Therefore, the Nestorian kayraks on the territory of the ancient settlements of Almalyk and Usharal allows us to presume that the ancient settlement of Usharal are the ruins of the city of Ilibalyk mentioned by Getum I as the city located very near Almalyk.

Archaeological exploration of the ancient settlement of Usharal – city of Ilibalyk (Republic of Kazakhstan, Almaty Region)

Aims:

1. The exploration of the large medieval city (ca. 10th to the beginning of 14th centuries) on the Great Silk Road;

2. Geo-archaeological explorations, research and excavation of the Christian heritage sites (gravestones, remains of cult constructions;

3. Introduction to the scientific community of the new materials related to the history of Christianity in Eurasia during the Middle Ages.

Purposes:

- Identification of the borders, topographical studies, and layout of the ancient settlement;

- Studies of stratigraphy and chronology of the ancient settlement;

- Excavation work on the territory of the site to include shurph (trail trench) making and excavation of an area of 100 square meters;

- Studies of the archaeological and numismatic collection and the preparation of ceramic typology and identification of coins;

- Preparation of a scientific report of the findings and two publications in the Russian and English languages.

Time frames

Total period of project implementation – 2016-2018;

2016 – 1 month (May, June or August);

2017 – 1 month (May, June or August);

2018 – 1 month (May, June or August).

Expected results:

Studies of the topography, preparation of the topographical plan, geo-archaeological studies, and excavation work are expected to provide materials (ceramics, coins, metal objects, bones etc), which will allow for the identification of the ancient settlement of Usharal as corresponding to the city of Ilibalyk mentioned in written sources of the 13th century. Research of the remains of Christian heritage, such as gravestones (kayraks) with Syriac and Christian symbols can provide new information on the spread of Christianity along the Great Silk Roads together with its role in the cultural life of the Mongolian Empire and Chagatai State as well as its connections to other religions.

1.2 The Usharal citadel in view of the archeology and historiography of the northeast Zhetysu (Semirechye) region

The powerful Mongolian Empire formed in the 13th century. Extremely complex historical circumstances taking place in Eurasia in the 13th and 14th centuries contributed to alliances which seem very strange at first glance. The Pope, the Russian grand princes, the Il-khans of Mongolian Iran, the kings of France and Genoese merchants, monks of the Franciscan and Dominican orders, the rulers of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and various courtiers of the great Mongol Khan all sought partnerships and alliances during this period.

Direct contact between East and West ended around the 1340s as the Mongol Empire terminally collapsed due to its bulky and fragile political system, which prevailed in Asia during the conquests of Genghis Khan and his immediate successors.

Therefore, the 13th and 14th centuries were narrated by travelers who would go one after another to the horde of the Great Khan in Mongolia proper. Their reasons varied. Some were searching for allies against their enemies; others would seek to arrange trade deals supervised by their new conquerors; still others would speak on behalf of their subjects to ensure their protection from the greed of the Mongolian overlords; while, finally, some were just spies and schemers. These ancient "explorers" left their diaries for us or dictated their impressions to historians. Some travelers remain only in memoirs of their contemporaries. The records vary in significance due to the motives of their travels and the personal qualities of the explorers themselves.

Among the names of the great explorers and travelers of that time stand the famous Venetian Marco Polo; the ambassadors of Pope Innocent IV; a Franciscan monk, Plano de Carpini; a Frenchman, André de Longjumeau; the Italian monk, Nicolas Ascelin of Lombardy; an unofficial ambassador of the French King Louis IX and missionary monk William of Rubruck. Of special note also was the great Arab traveler, Ibn Battuta, who traveled more than 75,000 miles through West Africa, India, Spain, Turkey, Iran, the Volga region and Central Asia. Of special note to our study as one who should be included among these names is the king of Cilicia Minor, Getum I.

During the 1230s, the Mongols invaded Greater Armenia, the rulers of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia at first avoided invasion nestled behind the high ridges of the Taurus Mountains. But in the 1240s, King Getum I, secured his small country from the Mongol wrath by accepting vassalage, thus acquiring strong allies. Yet, problems remained.

Getum sought an audience with Möngke Khan in 1253 by leading an embassy hoping to end the harassment of Argun, the Mongolian overlord of Transcaucasia, who was imposing high taxation. Though a king, he left secretly and under disguise, playing the role of a mule driver. His small delegation made it to Karakorum, the Mongolian capitol following a route, which today is little known. Their only references during their travels to Karakorum are to the Volga and Yaik (today’s Ural) rivers, the land of the Naiman and the Qara Khitan state. Möngke’s court welcomed the delegation warmly. Getum secured an agreement with the Mongols and got promises to reduce their tribute payments. On November 1, 1254, Getum I left for his homeland "via the way, which he had (earlier) covered in secretly, he was now returning like a lion..." The return route, detailed by this source, is of great interest.

From Karakorum "He [Getum] arrived in Gumsgur, [from there] he went to Peraleh, [then] Peshpalek ... From there he went via Arlek, Kulluk, Enkakh, Tchanpalekh, Khutapa and Ankipelekh.

Then he came to [East] Turkestan [and] onward to Ekopruk, Dinkapeleh and Polat, passing through Sut-Gol and Milk Sea, he arrived in Alauleh - (Almalyk) and Ilanbaleh - (Ilibalyk), and then, having crossed the river called Ilansu, reached the foothills of the Taurus Mountains. He arrived in Dalas (Taraz), and from there, went through Otrar, Jizzakh, Bukhara, Tabriz, and returned to his homeland. " This list contains the names of cities that are already precisely located, which are Almalyk and Taraz, (called “Alaulehu-Almlyk” and “Dalas” respectively).

This categorized route allows one to specify the location of “Ilanbaleh” (Ili-Bali according to the Chinese sources and Ilibalyk per the Muslim ones dating between 1329-1331). However, due to the fact that archaeologists could not locate a citadel corresponding to this city for a long time, the history of its search dragged on. Nonetheless, various localities for the city have been proposed.

In 1893-94, the orientalist V.V. Barthold, made a research trip along a route that included Tashkent, Shymkent, Pishpek [today’s Bishkek], Kegen, Zharkent, and Verny [today’s Almaty] in which he identified a number of medieval towns with specific archaeological sites. The scholar believed that Ilibalyk corresponded to the modern town of Ikioguz, based on a message by Mahmud al-Kashgari (12th century) also called “Equius” by William of Rubruck (13th century). Bartold proposed to identify it with the Chingil'dy site, which was located on the right bank of the Ili river on the Verny [Almaty]-Zharkent route, 35 km to the east of the crossing of the Ili river.

Interestingly, the first one to mention the site of the ancient Chingil'dy settlement was C.C Valikhanov, the famous Kazakh explorer and cartographer of the 19th century, due to the finds of water ducts there . A.N. Bernshtam agreed with the identity of Ilibalyk at Ikioguz-Equius and placed it at the spot of the Chingil'dy site as well .

Later excavations conducted in the Ili Valley (northeast Zhetysu) region revealed, however, a few dozen new medieval sites and proved conclusively that the city of Iki-Oguz mentioned by Mahmud al-Kashgari and called Equius by William of Rubruckhould actually be identified with the Dungene site located 20 km to the west of today’s Taldykorgan, in the Kazakhstani village of Balpyk-Bi (formerly known as Kirov). The identity of Iki-Oguz/Equius with the Chingil'dy site came into question, since the latter is actually is the remnants of a small settlement, most likely a caravanserai.

Finally, in 2014, new evidence emerged that supports the identity of Ilibalyk at the Usharal site more confidently. First, the location yielded a rich collection of coins, which in itself testifies to the importance of the city, which stood on this site. Three coin hoards and 123 finds of individual coins have been discovered. All three hoards are composed primarily of dirhams dating from the 13th to 15th centuries. These hoards can be described as follows:

Hoard 1. Copper silver-plated Almalyk dirhams [656-660/1258-1262]. Total quantity of eight coins. Hidden in the first half of the 660s/1262.

Hoard 2. Consists of seven silver dirhams of the Chagatid State (during the rule of Kaidu). The hoard was hidden at either the end of the 13th or beginning of the 14th century.

Hoard 3. Consists of 40 silver dinars from the 14th century. The hoard dates no earlier than the 740/1340. It was possible to fix the dates 37 of the coins, of which 36 are from the State of the Chagataids and one is a coin of Ilkhan Abu Zaida.

The set of individual finds can be divided into three groups. The first group has coins minted before the Mongol conquest, the second group are coins from the great Mongolian Empire, the third group are coins of the State of the Chagataids. From the 123 coins, no coins were minted later than the middle of the 14th century.

Seven of the coins (comprising 5.7% of the individual coins) are Qarakhanid dirhams dating to the 12th and 13th centuries and correspond to the first group referenced above. The oldest of these is the dirham of Bughra Karakhan minted in Tunket in 444/1052-1053. Two coins are attributed to the Northern Song dynasty in China, the oldest of which dates from the beginning of the 11th century is by tian-sheng yuan-bao (the issuer's imprint was used between 1023-1032). This group also includes one silver dinar and a chip of a large copper silver-plated dirham dating to the early 13th century. The dirham was minted either by the Qarakhanids or the Anushteginids’ Khorezmshahs. In total, this first group consists of 11 coins, comprising 9% of the 123 coins.

The coins of the second group include 93 items, almost 76% of all the numismatic finds. The greatest period of commercial activity in this locality, according to the collected information, occurs specifically between 630/1232 and 666/1268. The composition of one of the coins from the Mongolian Empire contains a chip of a gold dinar (perhaps the dinar itself had been minted even before the Mongol conquest), as well as 12 silver dirhams. However the greater part of the coins from this period is made of copper silver-plated Almalyk dirhams and copper felse minted during the reign of Möngke Khan and soon after his death. Of particular importance is the fact that the Mint of Almalyk struck the vast majority of the Imperial coins found at the site of the Usharal citadel. Thus, the city of Ilibalyk in the 13th century was in the sphere of the economic influence of Almalyk, a metropolitan center of the Ulus of the Chagataids and located no more than two days away from Ilibalyk. Even the small number of silver coins found dating to the first half of the 13th century indicates the continual supply of dirhams the markets of this city traded in starting from 630s/1233 until 662/1264. Copper silver-plated dirhams stretche the chronological chain to 666/1268.

In addition to the Almalyk coins the complex of individual finds holds coins struck by the neighboring Mint of Kayalyk (the modern village of Koilik), as well as by the mints of Pulad and Imil, and of a yet undetermined mint. Quantitatively speaking, of the 93 coins in this second group the silver dirhams total 12 coins (13%), and the greater amount being to the copper falsies (16 coins = 17%) and the copper silvered-plated dirhams (68 coins = 70%)

The third group of coins is not very numerous with a total of 16 coins (13% of the total individual finds). However, the composition of this monetary grouping is completely different in quality. The third group contains 11 silver coins from the total, or 69%. The youngest of the coins are Almalyk felses with the Uighur legend in the field and the year of 742/1341-42.

Both the hoards and the individual finds recovered on the site of this city indicate trade utilizing currency during the 13th as well as the first half of the 14th century in the city. The numismatic finds demonstrate that the city already existed in the beginning of the 11th century. It remains hopeful that over time it will be possible to collect sufficient information on the coin finds sufficient for statistical association to draw up a numismatic schematic of this citadel which can more conclusively identity these finds with the city of Ilibalyk.

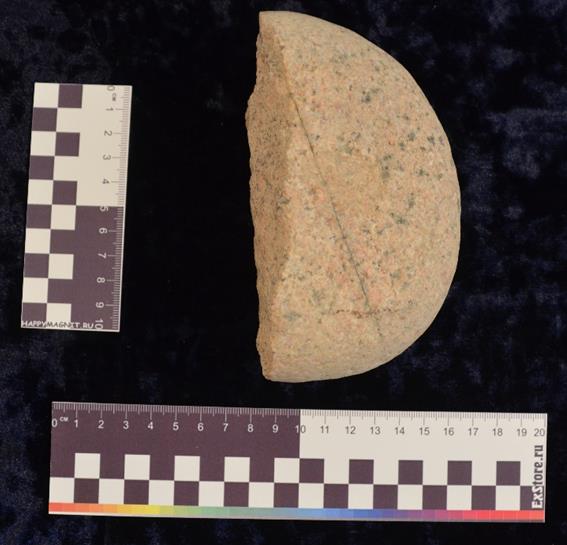

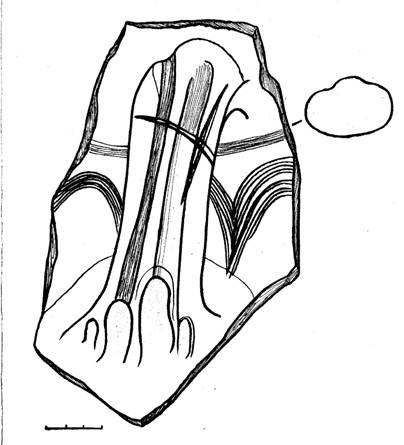

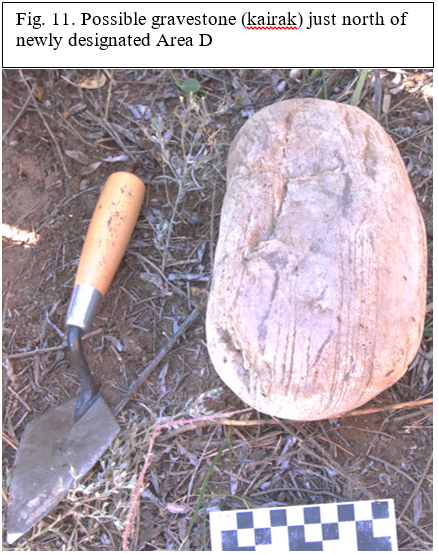

A second identifying factor, a kayrak, or gravestone, with a Nestorian-styled cross and inscription was found near the site of the ancient citadel in 2014, although, the inscription is yet to be deciphered. This entire project got its spark in 2014, when a school teacher near the Ilibalyk site reported to the Kazakhstan Archaeological Society the discovery of a rather large gravestone (perhaps the largest of its kind ever discovered) with a very discernable cross carving and inscription. Prior to this time, no gravestones of this sort had ever been found within the borders of Kazakhstan. All previous stones of this type within the sphere of former Soviet Central Asia were discovered in Kyrgyzstan. Others have been discovered in China, including the ancient city of Almalyk. All of these stones came to light between 100 – 120 years ago. The connection between Almalyk appears significant since Nestorian kayraks now appear to be located in two adjacent medieval Silk Road sites.

Muslim sources, according to V.V. Bartold, mention Almalyk just before the Mongol domination. It was the capital of the sovereign Ozar (Buzar), who went gradually from being a robber and a horse thief to the ruler of Almalyk and several neighboring cities. Later, he voluntarily submitted to Genghis Khan and his dynasty continued to rule Almalyk for at least two generations. The location of the city was defined via the route as outlined by Changchun Tsi, who placed the city at a distance of one day’s travel to the west of the Talki pass on today’s border between Kazakhstan and China.

Further evidence for Almalyk’s location in conjunction with Ilibalyk is what was known concerning the time it took to traverse between the various cities. For example, the way from Otrar to Almalyk took approximately 45 days and from Almalyk to Bishbalyk (the Uighur capital of the 10th century) another two weeks. As the main city of the Chagatid domain, Almalyk served as one of the centers of medieval European missionaries who promoted Catholicism in the Mongol realm. In the 1330s, under Changshi Khan, the Catholics maintained a church and bishopric in Almalyk. These activities came to an abrupt end when a small, but bloody massacre against Christians occurred under the Chagatid ruler, Ali Sultan in 1339 or 1340, due to his sympathies with Islam.

Most likely, V.V. Barthold visited the ruins of Almalyk, along with the ruins of the Tughlugh Timur mausoleum, who died in 1362-1363. Tughlugh was the first of the rulers of the eastern part of the Ulus of the Chagataids who officially adapted Islam. V.V. Barthold described the Almalyk mausoleum and noted the similarities in style with similar structures in Central Asia. Adjacent was another smaller mausoleum belonging, according to locals, to the son of Tughlugh Timur, Shir-il'khan.

In 1902, N. N. Pantuson, an orientalist and graduate of St. Petersburg University who held high positions in the administration of the city of Verny (today’s Almaty), visited Almalyk. In Kuldzha (today’s Ili, China) he saw finds from Almalyk, which included two gravestones with crosses and inscriptions engraved on them.

Thus, the finds of the Nestorian kayraks at both Almalyk and the 2014 find in Usharal also support the argument that modern Usharal is them site of the ruins of Ilibalyk, mentioned in the roadmap of Getum I as immediately coming after Almalyk when traveling from east to west.

1.3. Methodology of archaeological research of settler-type sites

This part of the scientific project report describes the methods and procedures applied to the stages of scientific and research work related to the settler-type site. Depending on the context and situation, some of these procedures were expanded or eliminated completely. During the excavations of the medieval site of Ilibalyk a common research method for such sites was applied. The situation and context determined the various individual approaches during the excavation.

The methodology envisaged complete excavations on site with the purpose of reaching to the level of the original surface. Since the excavation covered multilayered sites (settlement, citadel, etc.), at times excavations reached only the cultural layer, belonging to a particular construction horizon and covered until the entire site was investigated or at least the target object with the adjacent territory.

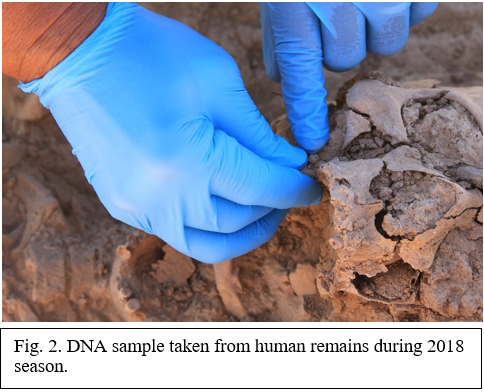

Sites in which additional information by methods of the natural sciences could be obtained were studied using the expertise of specialists of the natural sciences through taking appropriate samples for later analysis (i.e., soil scientists, geologists, geo-morphologists, paleo-botanists, etc.).

Excavations on the archaeological site were preceded by a detailed examination of both the site and the surrounding area as well as the mandatory preparation of an analytical topographic plan and comprehensive photographic imaging.

The choice of location for the excavation layout of the site and determination of their sizes was dictated by the study.

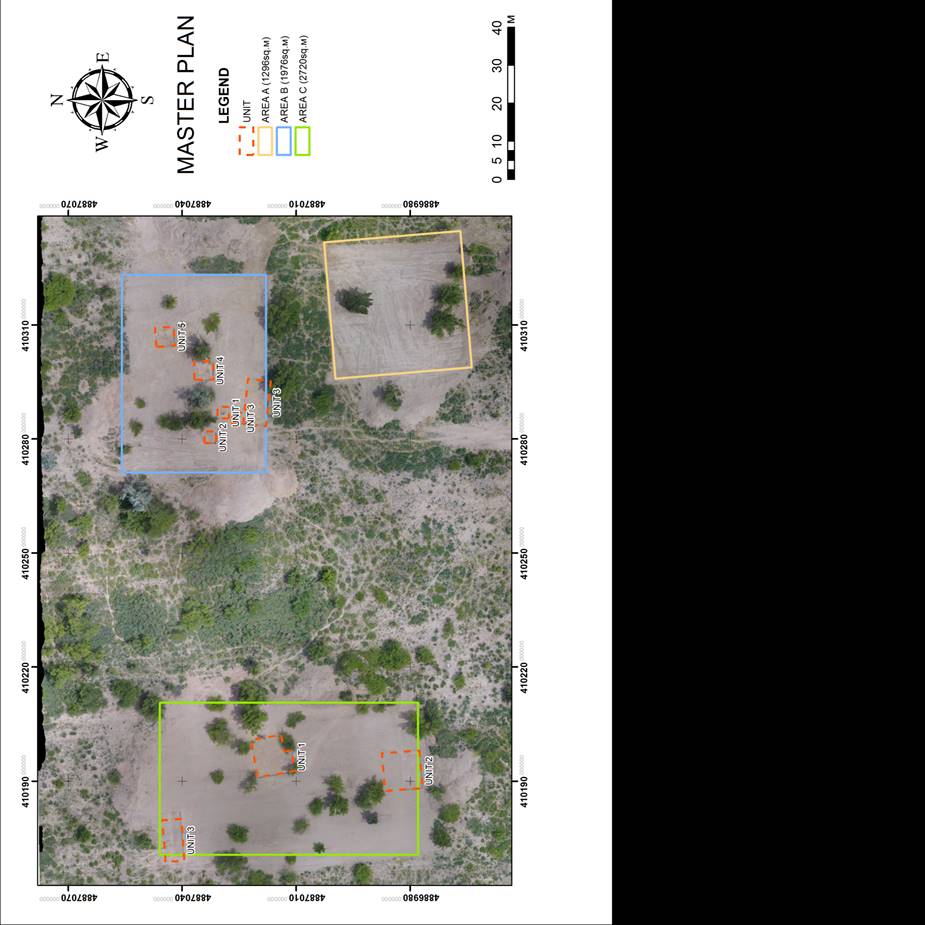

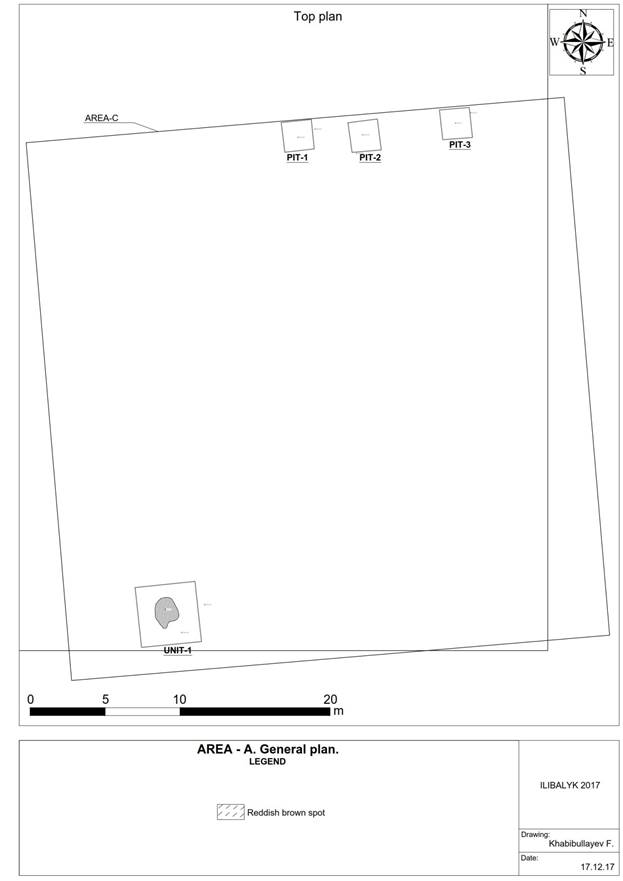

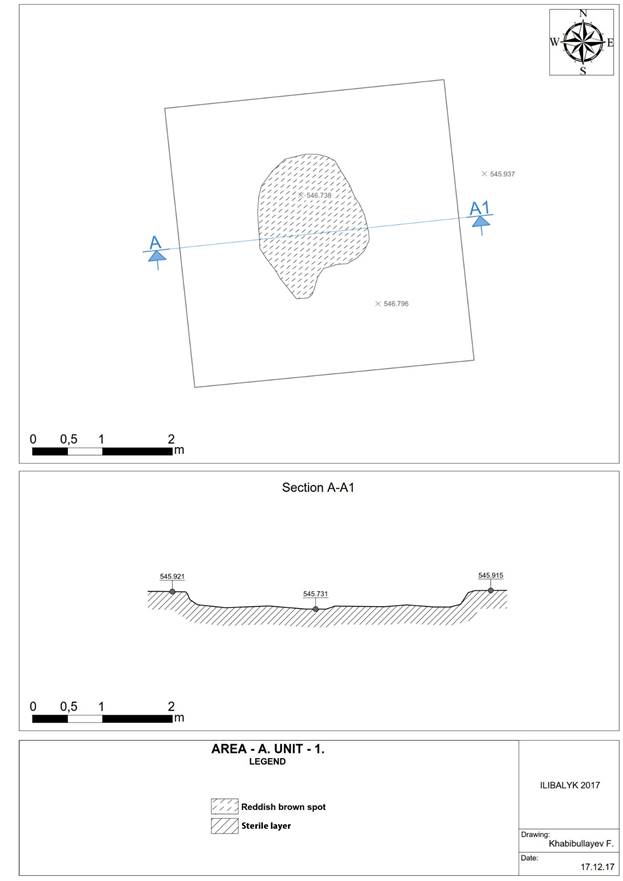

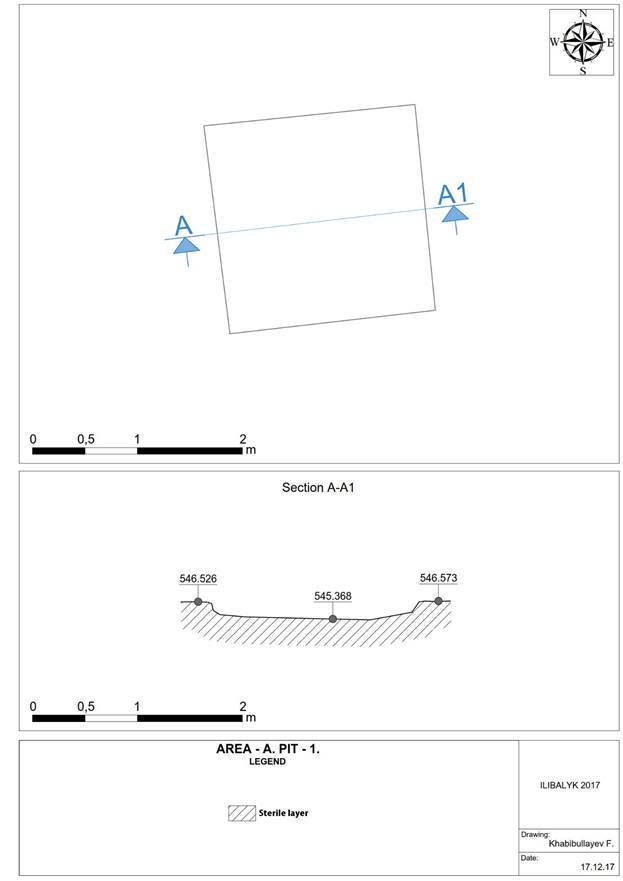

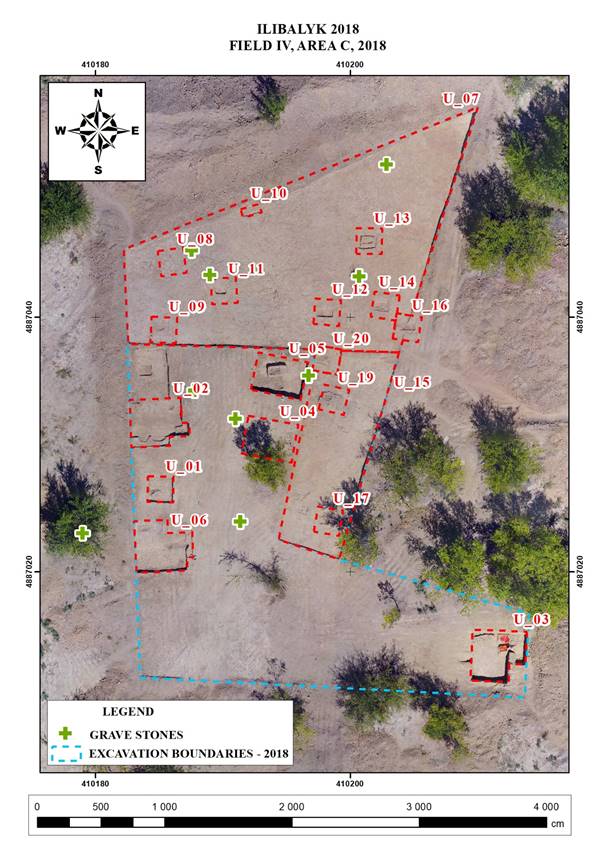

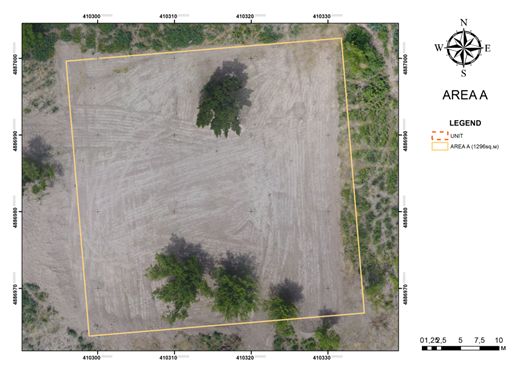

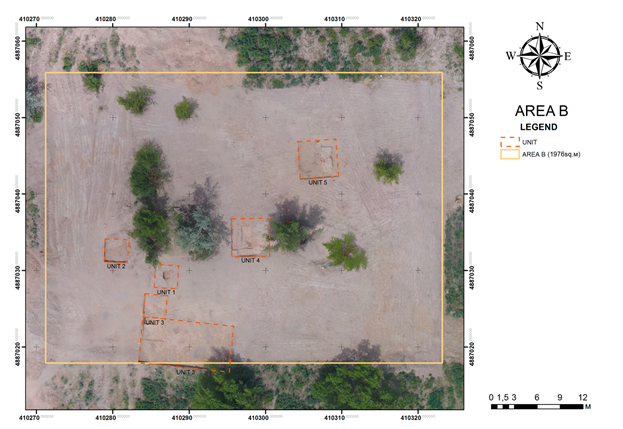

Initially, photographic images of the terrain were performed using an unmanned aerial vehicle (drone), a topographical plan was conducted using a total station, and surface material was collected.

The process of excavation was accompanied by photography. Identified designs were subject to clearing, they were instrumentally recorded and described. The process of photographing the excavations was considered essential, starting with the overall appearance of the site and its surroundings which was selected for investigation at the various levels of the excavation layer, as well as of all objects which become apparent such as foundations for walls and structures, hearths, sufas, courtyards, streets, vessels and their fragments, and stratigraphic profiles etc.

All types of work on the excavation and analysis of the cultural layer, clearing constructions loci, floor plans and finds were done exclusively by hand, using shovels, trowels, scoops, and brushes. The entire excavation area was cleared of the topsoil to a depth of a spade (25 cm) and then carefully balked and swept to detect traces of building structures, location of midden pits, various stains, and ash accumulations. As the excavations proceeded, the soil was removed from the excavation unit and dumped into heaps. Layer-by-layer finder were collected conducted which included pottery sherds, kitchen residues of domesticated animals (osteological material), metal or other objects.

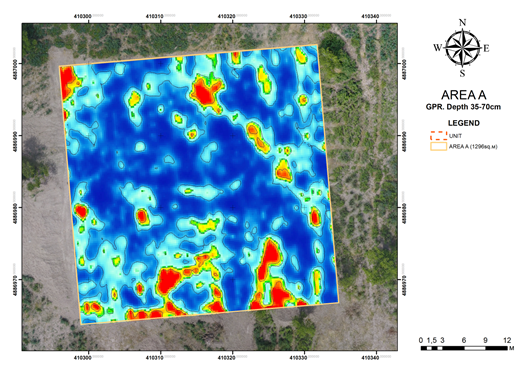

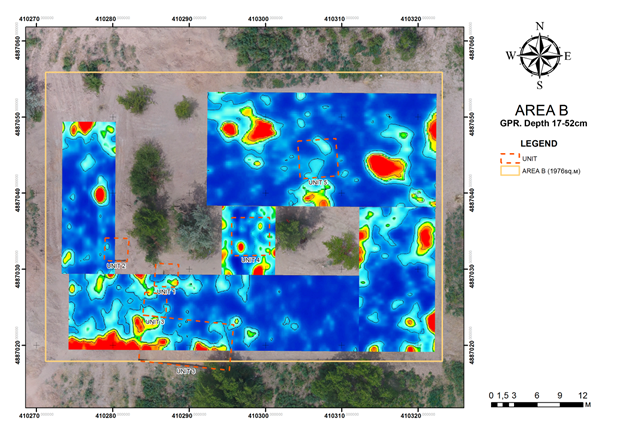

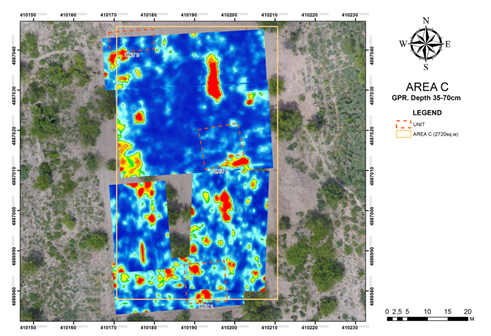

In order to determine the precise location and features of the hidden archaeological objects, researchers applied non-invasive remote sensing methods. In the case of the Ilibayk site a geophysical scan of one individual section of the territory was conducted.

Analysis of the soil layer was carried out with careful observation of the ground for finds, with special consideration of bare structural loci and layouts. After removing each layer, the surface was swept clean, and a visual survey conducted of the unit for architectural and other loci. Then workers conducted a layer-by-layer penetration (approx. 25-30 cm) until reaching the original level of the entire unit of the excavation or at some pre-determined level. This was followed by sweeping and documentation.

Researching the Ilibalyk citadel required careful identification and systematic pinpointing of all the cultural layer’s artifacts (i.e., fragments and entire ceramic vessels, iron objects and objects made of other materials); remnants of walls and foundations of residential, industrial and religious premises; district planning loci; streets; houses; manor houses their and premises. All layers and objects found on the excavated sites of the ancient citadel were documented. During excavations, the graphic documentation should recorded the location and depth of all finds, including the ones badly damaged and displaced, since this data was considered important to recreate the original structure and topography of the ancient citadel and overall site.

Investigation of cultural deposits occurred all the way to the original surface level, unless the construction and architectural remains uncovered during the excavation process proved significant and preservation was considered necessary, thus altering the process.

While identifying the cultural construction layers and architectural remains, work was conducted to preserve so that these remains until they could be identified and comprehensively catalogued. While not significant constructions were identified, backfilling did take place on all the sites.

Those constructions in a poor state of preservation and which were not intended for conservation, then the research plans included continuing the excavation of selected sites and for the purpose of revealing more features. After proper recording, each feature was eliminated and the plot was leveled and excavation continued until the required cultural layer was reached.

The excavation process included daily record keeping from the field that reflected all the structural features of the cultural strata and various observations. Field records served as the basis for the drafting of this scientific report.

This year’s project (2016) did not reveal any features that required conservation for tourists or further research purposes. Therefore, all three sites were back-filled.

Had such features been uncovered, conservation and restoration work would have been conducted on the basis of field observations during the excavation and through the experience of similar works in the citadels and cities of Semirechye (Zhetisu) and southern Kazakhstan. Archaeological knowledge and conservation techniques and restoration of settlement sites with adobe architecture are of particular importance. Materials with identical or similar physical and chemical properties found at the archaeological sites are used for restoration. They should ensure historical authenticity, resilience to adverse external influences and have high presentation properties. This is the technical conservation philosophy whereby this project was carried out.

All uncovered artifacts were recorded, described, documented and logged into an official inventory of the collection. At the end of the investigation, the excavation was subject to reclamation (back-filling), as mentioned above. The entire process was fully recorded and the results are presented in the form of this written report describing the finds, illustrations, photo appendices, and drawings and graphics appendices.

All photographs of features included the use of a scale ruler and/or surveying rod indicating which direction the camera lens was set.

During the investigation, identification and cataloging took place of all findings that included objects, artifacts, layers, pits, and various structural features. The finds were fully scrubbed, cleaned and restored where possible, drawn and/or photographed and positioned next to a scale ruler.

All artifacts were catalogued with the exact location and depth of the finds and indicating the point of their location on a separate plan. Materials were stored in packets with a label indicating the raw data. The label was placed in a separate small package to prevent damage. Artifacts obtained during the excavation were taken for museum storage and further scientific processing.

The legislative basis of the work:

All work is carried out on the basis of:

- the law of the Republic of Kazakhstan no. 1488-XII dated July 2, 1992

"On the protection and use of objects of historical and cultural heritage";

- Order MCS no. 156;

- Order MCS no. 157;

- Order MCS no. 376;

- Other normative and legal documents of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

2 RESEARCH SENSING

2.1. Geodesy

At this time, as a result of the integration of modern technologies in the area of scientific investigation, various pieces of modern engineering equipment were utilized. One such example is the use of Total Stations, 3-D scanners, high precision GPS and geo-radars to document archaeological sites. The use of this equipment enables extra precise measurements over a short period of time.

In turn, Archaeological Expertise has adopted the latest equipment for documenting and studying both surface and buried objects applying non-invasive methods. The investigations for this project involved the company using the following equipment: Leica TCR 307, 407, TC 407 laser total stations, HDS3000 3D scanner, Trimble R3 ultra-precise GPS tracker, GSSI SIR-3000 geo-radar with a 270 MHz frequency antenna.

The main tool for documenting the sites during the archaeological dig was the total station. This apparatus provided high-precision topographic survey plans of hills and cross sections. Data acquisition was accelerated and convenient due to the fact that the data acquired from a total station is digital.

The Trimble R3 GPS tracker enabled high-precision documentation over large areas. The advantage of this method is this technology’s high speed and accuracy of plane surveys and topography. In addition, only one operator was required to carry out the survey because the device is not attached to fixed positions, thus, one can use it on sites with complex terrain as well as over very large areas which exceeds the range of any Total Station.

A surface survey was conducted of the terrain layout, including the roads, communications, the surrounding infrastructure, hydrology, etc. With the help of the high-precision Trimble R3 GPS receiver a triangulated polygon for project planning and surveying was created. As a result of the research the following data collection and processing method was used:

- An arrangement scheme

This represents a set of information containing communication data related to roads of all types (central/main, dirt), the water resources (rivers, streams, lakes, etc.) and the power lines. All information is overlaid on the basis of topography.

- Surveying

This methodology involves a 3-D survey of the area based on the following:

Surveying technique: Topographic surveying of the object occured in two stages. The first stage involved surveying the micro-topography of each object individually. The advantage of micro-topography lies in its detail, allowing a researcher to determine the layout and features of the object under investigation based on a predetermined model with the ability to select a plot to conduct excavations using the received data. Micro-topography is run with a frequency of 1 m, which provides the possibility to construct a topographic model with horizontal increments equal to 0.2 m.

The second stage of the research involved a general topographical survey of the area and the surrounding landscape. This step facilitated the tracing of the overall arrangement and the relationship between the objects themselves as well as tracing the features of the cultural landscape. Surveying the general topography was made in increments of 10 m with horizontal increments of 0.6 - 2 m.

The peculiarity of the archaeological survey is that the information needed for this study was generated by applying different scales, that is, objects of interest are documented using micro-topography and the buffer area by applying common topography. In this regard, the work was carried out by a trained professional with an expertise in the field of archaeology.

The scale of the arrangement scheme was selected depending upon the area of the research objective. The maximum scale is 1:500 and then proceeds to 1:1000, 1:2000, 1:5000, etc. These limits do not apply to topographic surveying due to the archaeological specifics listed above. It is recommended that one use the following scale grid with a maximum scale of 1:50, then 1:100, 1:200, 1:500, etc., if applying intermediate scales a linear scale was required.

- Planned surveys

This method of collecting information can be both an independent method when conducting documentation and a complementary method to all other types associated with the use of a laser total station. Plan drawing carries the maximum amount of information. It is generated by object section with a plane at the level of 1 m or at the required height with an indication of the information in the drawing. The plan provided all the structural parts with feedback of the related information that included height-marking, explanations of the drawing and dimension lines. The composition of the plan drawings included drawings of individual parts, constructive units and other items requiring more detailed elaboration and carried out on a larger scale. Drawings were done in a linear scale ranging from a scale of 1:10 and less.

2.2 Using GIS technologies

Modern computer technologies have already proven their superiority when processing data. Combining computer technologies (especially data processing and analysis) and traditional maps has opened new horizons for cartography and resulted in the first Geographic Information System (GIS). Geo-information systems now combine precision and high quality digital maps; a tremendous amount of background information; a powerful set of tools for the processing and analysis of data; and also, the ability of specialized information exchange through the Internet. GIS - Geographic Information Systems are new technology that, despite its recent appearance, has spread widely across many scientific disciplines. GIS is successfully applied, for example, in such areas as forestry, water management, geology, economics, criminology etc. The very name itself does not provide the full gamut of a GIS system, below are some definitions that characterize GIS:

- a powerful system for collection, storage, processing, retrieval, and display of spatial data extracted from certain objects for specific practical purposes.

- an information system that generates data relating to spatial or geographic coordinates.

In other words, GIS is a system of databases with specific operational features applicable to spatial data.

- GIS is a computer system whose main purpose is the manipulation, storage, processing and generating of data about geographic space.

- GIS is not a single computer program, but a combination of several different computer technologies.

- GIS is an overlay of all kinds of data to its spatial environment (territory).

GIS for archaeologists is recognized as the best system with the ability to use the latter in the most extensive of studies. This is because the system allows for the analysis, management, and expression of the full range of collected data that is both spatial and having certain characteristics. This is absolutely necessary to maintain up-to-date with the constantly changing human environment. The program allows one to work on the restoration of an ancient landscape and provide further analysis of individual excavation structures, etc.

Despite their appeal, geographic information systems are criticized for its pronounced environmental determinism. Data related to the concept of "environment", such as types of soils, rivers and land usage can be measured, mapped and transformed into a digital format, while the cultural and social aspects are complex and therefore, problematic.

So, GIS technology is used to examine and process sets of various geographically related information. GIS is often used as a tool for mapping and analysis. There are a variety of methods whose use facilitates solving set tasks, and each method has its advantages and disadvantages. They are as follows:

Manual survey via a hand-carried map. -- very low accuracy, extremely time-consuming, low cost.

Instrumental survey (theodolite/total station) - high accuracy, extremely time-consuming, high cost.

Utilizing GPS - accuracy within 5-15 m, extremely time-consuming, low cost, problematic display on a map.

Topographic bases (100,000, 25,000) – Objects and features are not displayed due to their small size.

Geo-referenced satellite imagery -- extremely costly, yet high-resolution imagery.

Aero-photography -- no geo-referencing, distortion, not time-consuming, high cost.

GPS Rover survey (GPS measurement with high accuracy) -- extremely high accuracy, extremely time-consuming, extremely high cost.

The most appropriate way is a combination of these several methods mentioned above, combined into a GIS. This was applied during the excavation.

Гандзакеци Киракос. История Армении. Перевод с древнеармянского, предисловие и комментарий Л.А.Ханларян. Москва, 1976.

Байпаков К.М. Средневековая городская культура Южного Казахстана и Семиречья. Алма-Ата, 1986. С. 37.

Бартольд В.В. Отчет о поездке в Среднюю Азию с научной целью в 1893-1894 гг. Сочинения. Москва, 1966. Т. IV. С. 77-87.

Bretschneider E. Medieval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources. Fragment towards the knowledge of the geography and history of Central and Western Asia from the 13th to 17th century. London, 1888. Vol. I, II; 2-ded.:1910.

Бартольд В.В. Отчет о поездке в Среднюю Азию с научной целью в 1893-1894 гг. // Сочинения. Москва, 1966. Т. IV. С. 79-81.

Пантусов Н.Н. Надгробные христианские памятники в Алмалыке //Историко-культурные памятники Казахстана / Протоколы заседаний и сообщений членов Туркестанского кружка любителей археологии. Год седьмой (11 декабря 1902 – 11 декабря 1903 г.). Туркестан: «Туран», 2011. С. 265-267.

GandzaketsiKirakos. History of Armenia. Translation from the ancient Armenian, preface and comments by L.A. Hanlaryan. Moscow, 1976, p.p. 222-224.

V.V. Bartold “Report about the trip to Central Asia with a scientific purpose in the 1893-1894.” Works. Moscow, 1966. Vol. IV. p.85.

A.N. Bernshtam “Historic landmarks of the Alma-Ata region” Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR. Archaeological series. Alma-Ata, 1948. Vol. 1 (no. 48). p.89, Fig. 1, map insert.

For a history of these finds in English, see T.W. Thacker, “A Nestorian Gravestone from Central Asia in the Gulbenkian Museum” The Durham University Journal (vol. 59) 1967, 94-107. For recent publications on translations for several of these stones see Mark Dickens, “Syriac Gravestones in the Tashkent History Museum,” in Dietmar W. Winkler and Li Tang, eds., Hidden Treasures and Intercultural Encounters: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. (LIT Verlag Munster, 2009), 13-49, and Mark Dickens, “More Gravestones in Syriac Script from Tashkent, Panjikent & Ashgabat,” in Dietmar W. Winkler and Li Tang, eds., Winds of Jingjio: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. (LIT Verlag Munster, 2016)105-29.

2.3 Satellite imagery

Working with satellite imagery that are geo-referenced and have a resolution of up to 1 m provides researchers with information about landscape arrangement, water sources and all kinds of detail that are also available on a topographical basis, and are provided during the period of drawing these maps. At the same time, satellite images show the current situation of the research area.

2.4 Topographic maps and site topography

The use of a topographic base of 100,000 scale was utilized. A map with such magnitude provides the opportunity to review the entire territory around the research site. Also it provides a good basis for binding together smaller scale maps. This is implemented by using the same scale of geographical data adjustment of the GPS and aerial photos.

The use of a topographic base with a scale of 25,000 allows for a more detailed consideration of the research object as well as of the adjacent territory and can input into the GIS such loci as roads, rivers, canals, villages, etc. This creates the possibility of more detailed aerial photography, GPS and hill-by-hill referencing, digitization of topographic contours and, accordingly, moving the field documentation in a three-dimensional environment via computer.

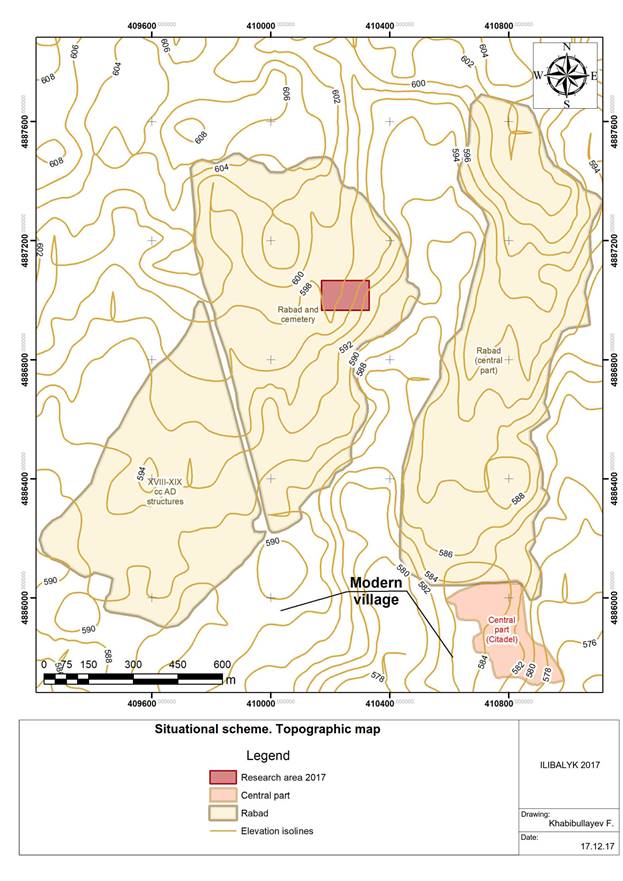

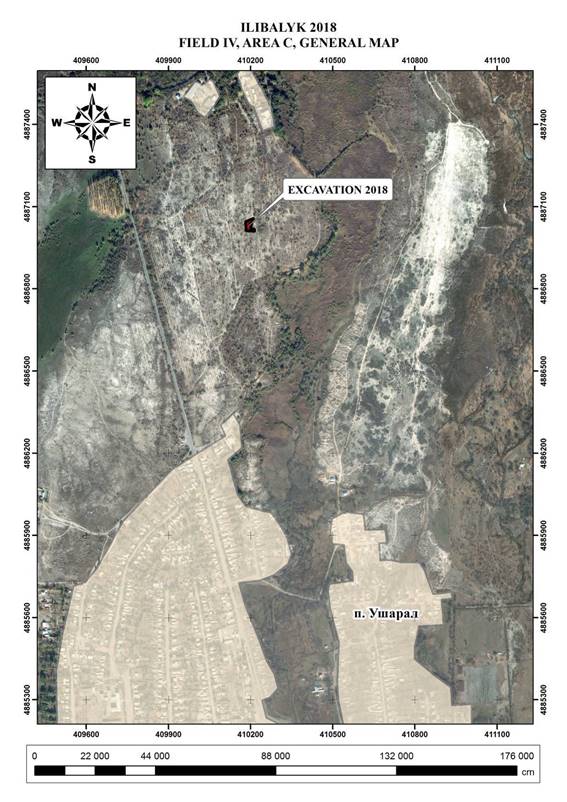

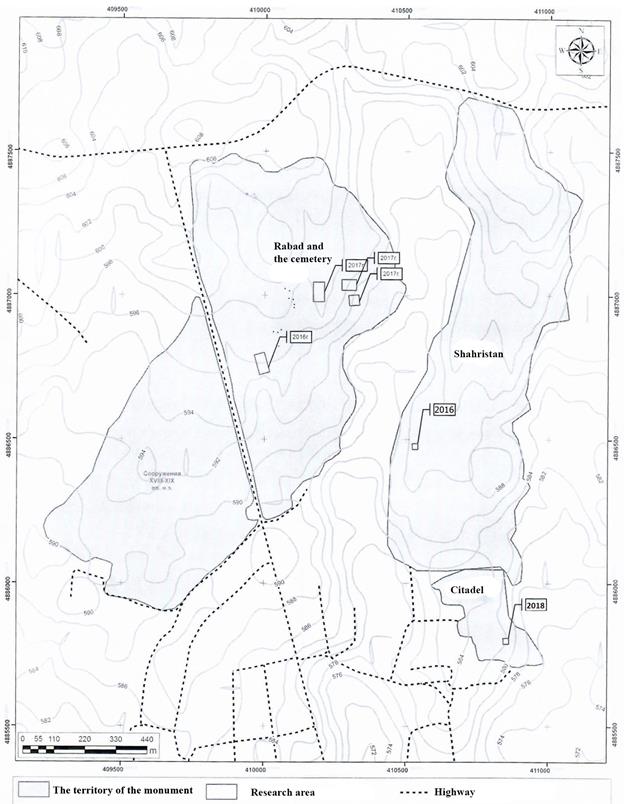

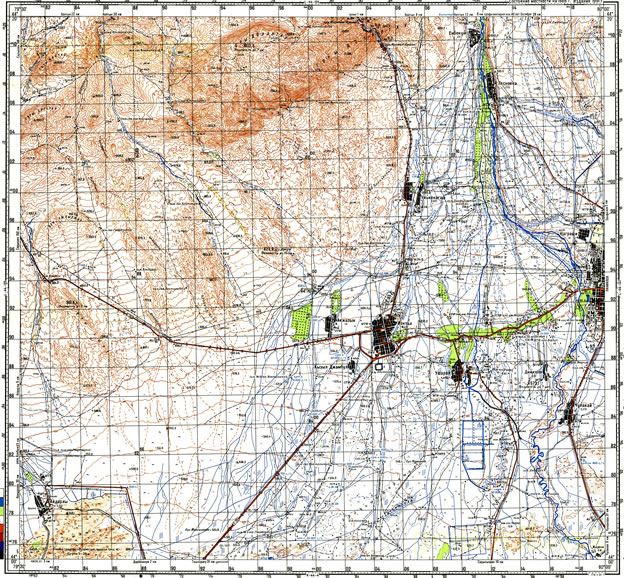

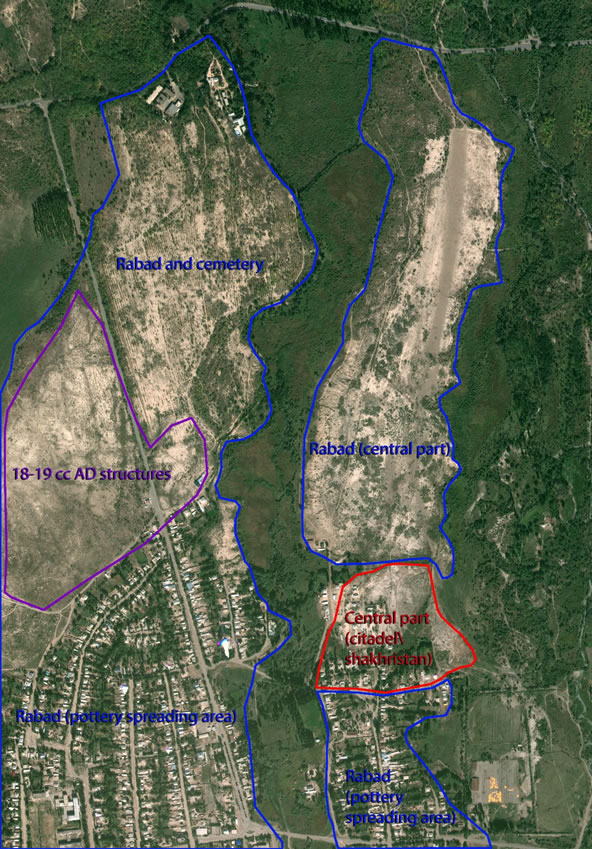

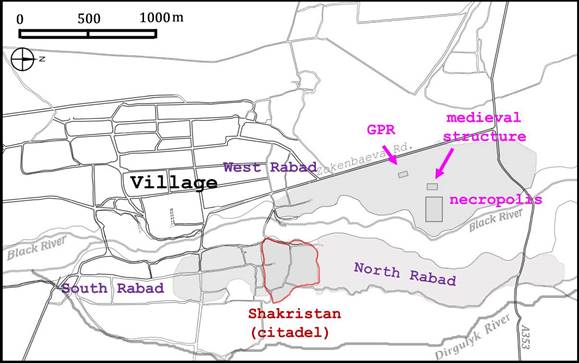

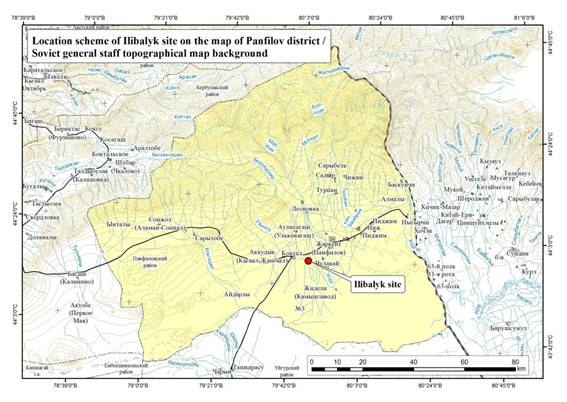

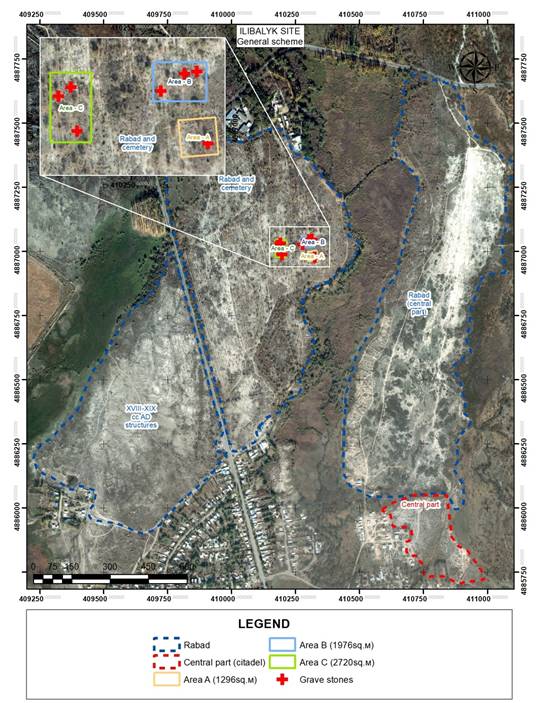

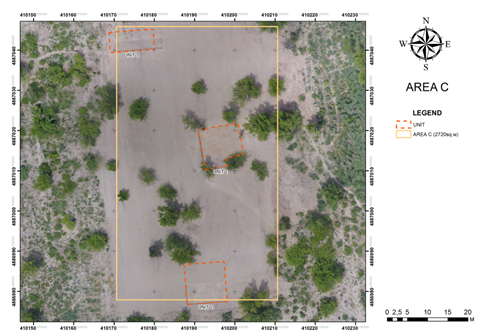

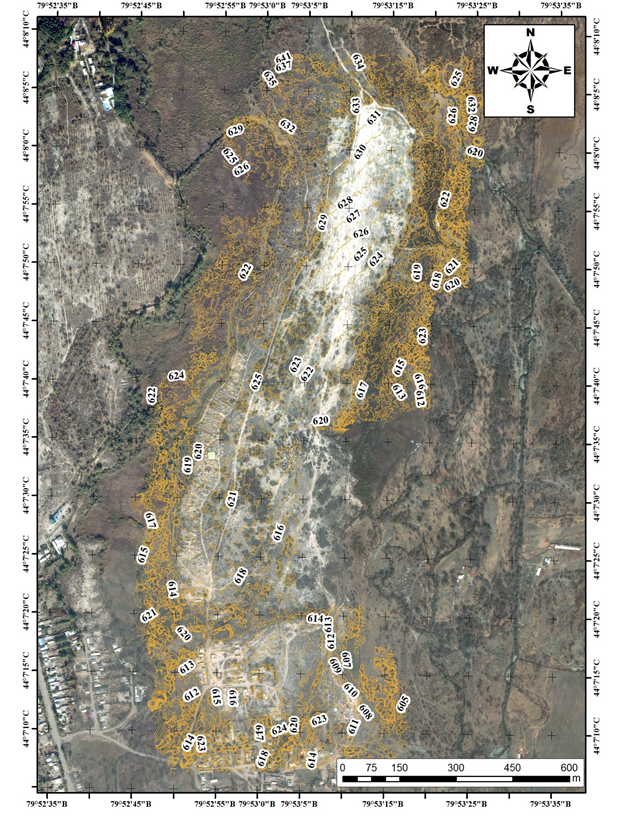

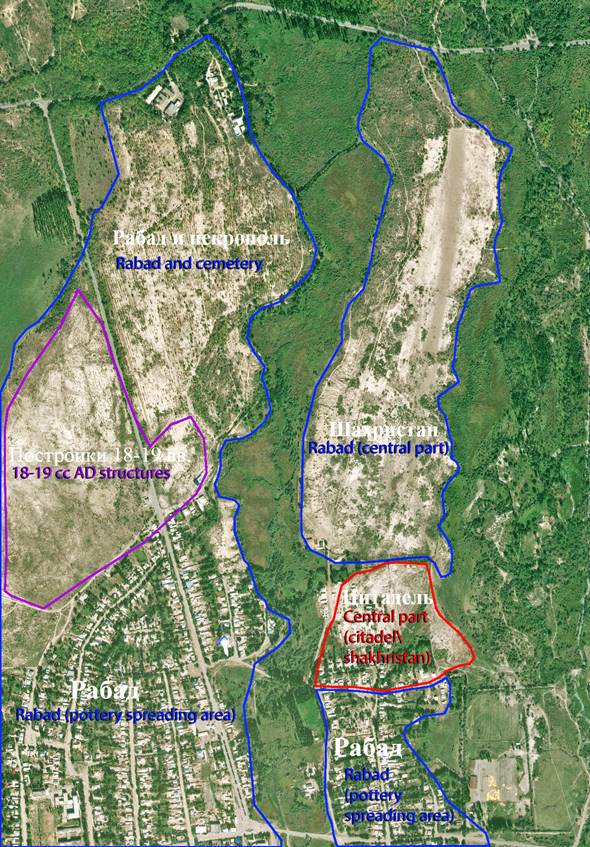

The site of Usharal (admittedly medieval Ilibalyk), as shown by studies in 2016, as per the area it occupies (the area of the settlement in this case is understood as the location of chronologically coherent and spatially concentrated cultural layers) is one of the largest settlements of the Ili Valley. The settlement is located in the south-eastern part of Almaty region, in Panfilovskiy district, Kazakhstan.

Usharal is geographically tied to Jungar-Alatau mountains region and interfluves of branches of Ili to the rivers of Usek and Borokhudgir. The foothills of the ridge of Toksanbay, Itshoky, Altyn Emel and Koyandytau located north and north-west of the settlement, are divided into ridges and crests and form local watersheds, which are nested with uneven-aged loss cones, cut by modern valleys. From the south-eastern side there are natural borders – sands of Muyunkum and Karakum, and to the south of the site – marshy spaces formed by the activities of Usek. The settlement is located at a distance of 30 kilometers to the north of the modern bed of Ili river. Described district, which occupies the area of about 500 square kilometers, is abundantly rich with water sources, which is clearly traced in the satellite snapshots. The site of Usharal is bordered by fertile land which is intensively saturated with river moisture. The ground waters are very close to the surface therefore the use of wells is possible here, although the abundance of pure river and spring water disputes the need for their arrangement, except for force majeure.

The structure of the settlement is difficult to describe, it is primarily due to an active and diversified economic development of the territory. The formation of the settlement is based on two over-floodplain terraces, elongated in the meridional direction. The terraces are cut by floodplains of branched beds of Usek. Rising above the river floodplains to a height of 9 meters, the eastern over-floodplain terrace (peculiar outlier) has overall dimensions of 1.8 km (latitudal direction) x 400-250 m (meridional direction), western – more than 4 km (latitudal direction) x about 1 km (meridional direction).

Eastern terrace is prominent and divided into three main parts: the central, of a rectangle shape, in size of 380x350 meters, dominating in terms of altitude. The absolute height of this territory is 620 m above the sea level; northern with dimensions of 1.4 km x 400-250 m and southern – 1.3 km x 350 m. The absolute altitude ranges from 620 m in the southern part of the terraces up to 630 m in the northern one. The total length of the terrace in the meridional direction is 3 odd kilometers.

Considering the analysis of the topology and topography of described territory, the location of the walls and channels, generality of the surface material, the central part of the medieval town (citadel and shakhristan) was located in the territory of central part of the eastern terrace, utilizing it as a natural platform. As described above, the shakhristan dimensions are 380x350 m. At the moment, the analysis of external factors does not allow to define the space of citadel in the outline of the walls of shakhristan, but, apparently, considering the significant reduction of the relief of shakhristan in the western part, the citadel can be hypothetically placed in the eastern, elevated, half of the represented territory.

The shakhristan, having an area of 10,500 sq.m. on the eastern side, is sharply broken by meandering floodplain of one of the beds of Usek, dominates over it and hole of Chulukay, which was also formed by prior activity of this waterway. The outer eastern wall was erected along the meander of Usek, which sometime, following its curvature undermined the terrace of shakhristan,. On the surface the wall is read by the elevation of 1-1.5 m. The quarry for ground winning, recently arranged in the south-eastern corner of the platform of shakhristan provides an idea on the material and specifics of walling of shakhristan.

The wall was built of adobe bricks with size of more than 25x30 cm, with wall masonry which actually started from the lower level of the floodplain. Thus, resting on the surface level of the floodplain, the body of the wall, adjacent to a natural platform of over-floodplain terraces, is interpreted as its liner with adobe bricks. Further studies should elucidate the details of these construction techniques, which were skillfully applied by ancient architects, apparently, with the purpose of saving the resources in walling by taking into account the features of the terrain relief. The width of the wall most probably reached not less than 5.6 m.

Outer southern wall partly destroyed by the modern landuse. Adobe masonry and falling down bricks are clearly visible.

Outer southern wall. View to the north

The southeastern corner of the outer wall of shakhristan which was partially destroyed by a modern quarry, is well defined. In this very part the wall, a little deviating to the south, turns to the west. It is possible to trace it in the terrain relief at a distance of about 250 m. Further to the west the line of the wall is destroyed by modern buildings. In this very part one of the meanders of the river outlines the boundaries of the central part (shakhristan) of the settlement from the east and the south in a natural way. There the terrace has a significant narrowing, actually decreasing up to 170 meters, extending to the south to a distance of 1.3 km with width up to 350 m. In the territory of this part of the over-floodplain terraces there are finds of bones and ceramic articles, but in much smaller amount.

The western line of the wall in the relief can not be traced, but by analogy it is possible to assume that it also stretched to the north, following the western line of the bed. The exact location of the north-western, south-western and north-eastern corners of the walls of shakhristan as per the satellite snapshots, projective and perspective aerophotos as well as full-scale survey of the territory was not found. However, the northern border of shakhristan is marked by sharp depression of several meters and a channel arranged in the latitudinal direction, cutting over-floodplain terrace and thus connecting the eastern and western beds of Usek. Perhaps the channel used today, was set up following the depression, which in turn was probably formed in the course of fortification activities of the northern side of shakhristan.

Traces of heavy robbery left by “black archaeologists” are covering huge area

In addition it should be noted that another modern agro-irrigation device arranged in the north-southern line, cuts the territory of shakhristan in the south-eastern part. Modern buildings occupy more than ¾ of the territory of shakhristan and are concentrated in its southern and western parts.

Nowadays it is impossible to assure whether the towers were arranged along the line of the walls of shakhristan.

The northern and, perhaps, the southern part of described over-floodplain terrace were occupied by the buildings of unfortified rabad. The peculiarities of relief do not provide detailed characteristics of architectural and planning features, including fortification elements of considerable scale. Therefore, the rabad is characterized as "unfortified". Surface gathering showed a continuous scatter of finds in the territory of a vast terrace area with the highest concentration along 70 meters width of the edge of the western terrace side. It is in this area there are clearly visible numerous gullies – the traces of denudation processes that might serve as the main reason for the presence of significant amount of surface material. Among the finds there are coins of Chagataid and Karakhanid appearance, ceramics, mainly of 13-14th centuries, ceramic slag, burnt bricks-plinthite, glass, coloured and black metal articles, osteological materials.

the western terrace in the north-southern line is 1,2 km x 600 m in the east-western line. The precise distribution of the cultural layer can not be determined due to two factors: firstly, the modern buildings from the southern side destroyed all visible traces of the ancient city, and secondly, from the western side a vast area (more than 600 000 sq.m.) of the terrace is occupied by the buildings of ethnographic time, most likely related to the presence of the Chinese population.

"Then they went to Turkestan, and from there – to Ekopruk, Dinkapaleh and Pulat and passing Sut-Gol and Milk Sea, arrived in Alualeh and Ilanbaleh; then, after passing the river, called Ilayesu, crossed the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, they reached Dalaye and came to the brother of Mangu Khan, Khulagu, who received the Eastern countries as inheritance."

«Soviet» topographical map 100k--l44-136--(1991). Учарал - is the modern village on the medieval Ilibalyk site

Topology based on satellite, aerophoto, land survey data

2.5 Aerial photography

In the process of this excavation, a new method for collecting and processing information was applied utilizing aerial survey/photogrammetry. A Phantom 4 quadrocopter (drone) was used to perform the job. It facilitated the gathering of a large array of information.

This technique makes it possible to work with small sized objects and cover large areas of research at the same time. Numerous flights at low altitudes (30-100 m) over a specific territorial location made it possible to photograph and apply a so-called "carpet" coverage method, which assumes the production of a large number of pictures with each subsequent photo overlapping the previous one by no less than 80%. In this way, numerous photos cover all of the spatial area of the site.

Aerophoto. Oblique view to the south. Citadel on the back view

Aerophoto. Oblique view to the north-east. Rabad and northern part of shakhristan

Aerophoto. Oblique view to the south. Shakhristan and citadel

Aerophoto. Oblique view to the east. Rabad “central part”

Aerophoto. Oblique view to the north. Rabad and cemetery

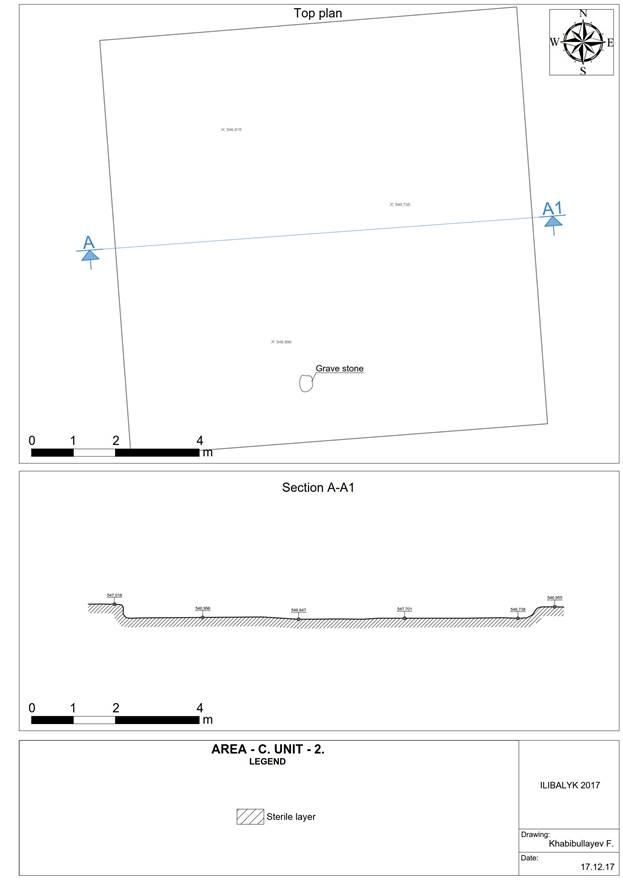

3. EXCAVATION 1

3.1 General description

This excavation was located in the western part of the rabad, of the Ilibalyk site (300 m to the north from the edge of Usharal village, in the Panfilov district). This location of this excavation was chosen after a careful analysis was made with unmanned aerial vehicle (drone). The selected plot looked like the remnants of rectangular building under the surface from the bird's-eye view.

Aerophoto. Oblique view to the south-west. Excavation 1 (area 1)

Prior to excavation, the plot was uneven: at the northwest, west and central sections there a small ravine was identified, and in the southwest and south opposite side a low hill was observed stretching from east to west (0.3 m). A large part of the excavation surface was covered with dense vegetation (Fig. 28-30).

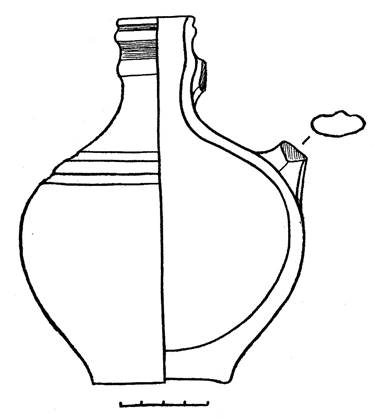

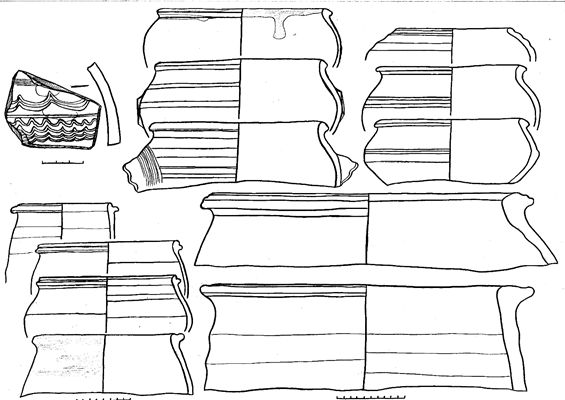

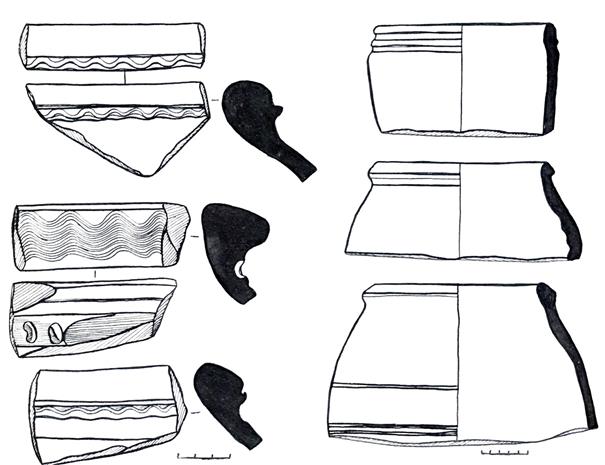

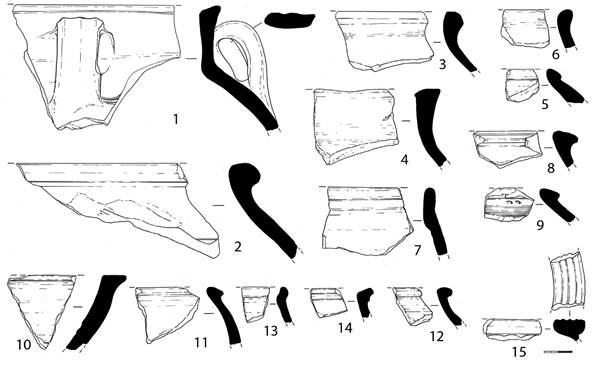

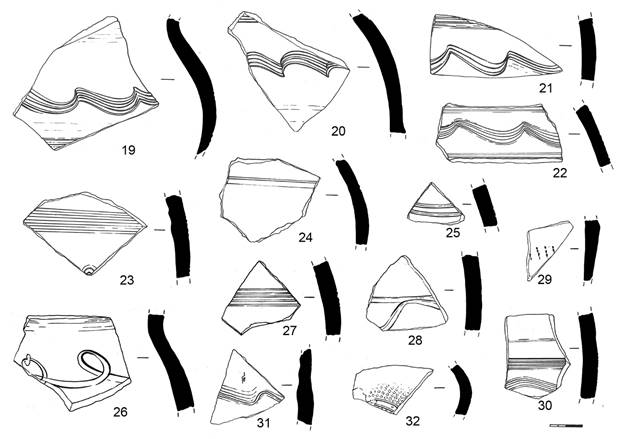

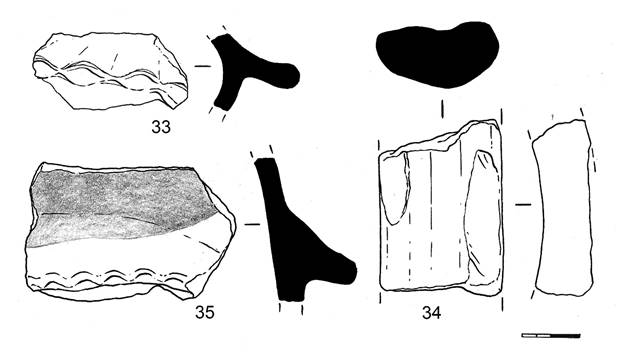

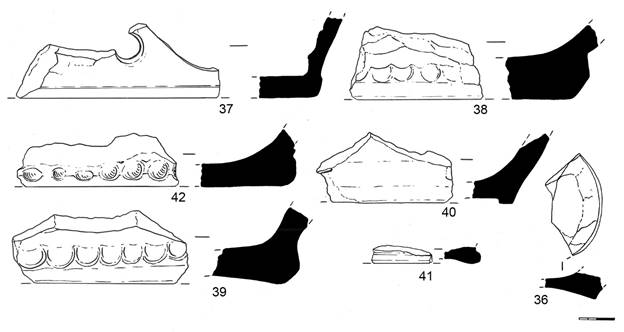

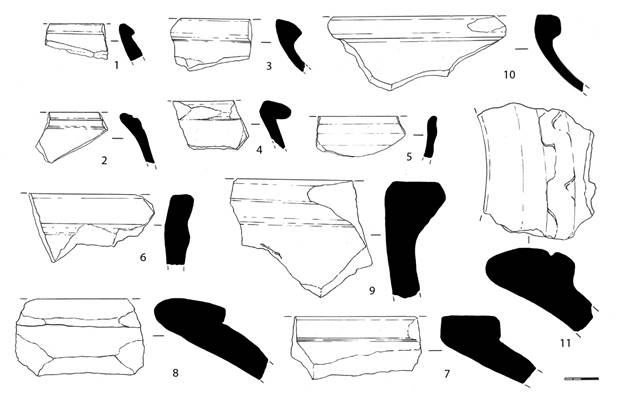

The works commenced with the clearing of surface material (Lo. 0), which was lying immediately on the visible surface (Fig. 35-36). In particular, many fragments of glazed red-clay ceramics, mostly from large thick-walled vessels such as pots and storage jars were gathered, along with fragments of jugs, bowls and pots. In addition to the pottery fragments, fragments of broken fired bricks, pebbles and bones of animals, mainly from goats and sheep, were collected from the surface.

After collecting the material from the excavation surface and the removal of organic growth, the plot was photographed (Fig. 37-40) and a layer-by-layer removal process commenced in steps equal to the half spade’s depth, or approximately 15-20 cm (Fig. 41-42). This topsoild layer was quite loose, loamy, and light brown. In the lower part of this layer revealed a large number of pottery fragments, the bulk of which concentrated in the southwestern, southeastern, eastern and central sections.

Aerophoto. Oblique view to the south-west.

Excavation 1 (area 1)

Following removal of the first layer and a thorough sweep of the excavated surface using brushes (Fig. 47-48) the surface was photographed (Fig. 49-54).

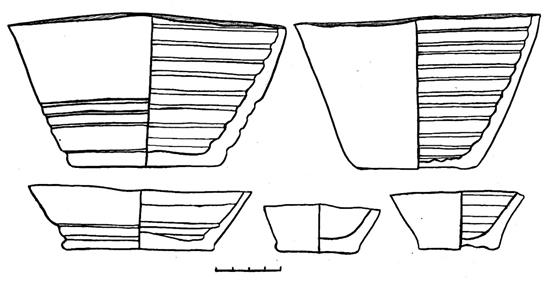

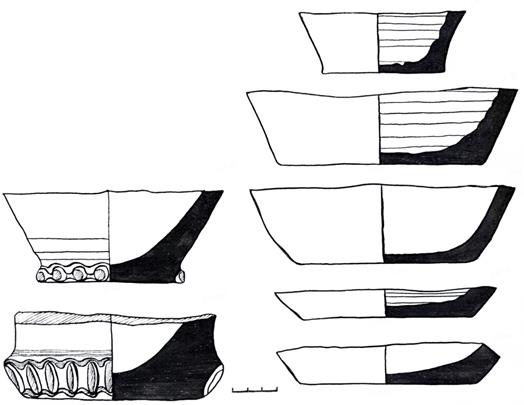

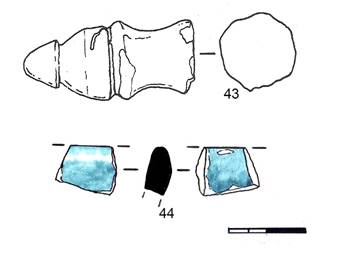

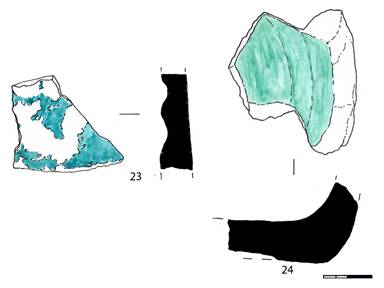

Excavation of the second layer, identical to the first in terms of the structure of soil and identified finds of pottery sherds, commenced. After removing the second layer, a depth of 15 cm, there several sites of fragment accumulation were identified consisting of pottery and bones. Among the pottery fragments were green fine-wear bowls covered with transparent glaze, blue fragments decorated with a floral ornamentation, turquoise ones with a black painted pattern, white ones with a transparent glaze, and others with brown and yellow glaze. The first cluster was found in the southwestern part of the excavation (Fig. 59-60); the second in the central part (Fig. 61-62); and the third one in the eastern part of the eastern edge of the excavation unit (Fig. 63-64).

In the course of removing the second layer in the northwestern corner of the excavation unit there a dense gray-brown sandy and loamy layer emerged (Lo. 9). The layer’s dimensions were 1.8 x 1.7 m; its thickness was 0.25 m (Fig. 67).

The southwestern part of the excavation contained a dense yellow soil layer (Lo. 10). The dense plot was 0.5 m thick (Fig. 68).

In the southern part of the excavation there was a feature resembling a collapsed wall with the dimensions of 3 x 2 m and a thickness of 0.3 m (Lo. 11). The layer, represented by yellow clay, was very dense (see Fig. 70).

In the northern part of the excavation revealed a dense layer 0.3 m thick (Item 12), with a rectangular shape with the dimensions of 3 x 3 m. The layer was light brown, perhaps the base of the wall (Fig. 71-72).

In the northeastern part of the excavation unit there two pits were uncovered (Lo. 13 and 14), round and oval in shape (Fig. 75-79). The pits were shallow, 0.3-0.5 m, filled with loose soil mixed with ash, inside were several pottery sherds and animal bones, some small fragments of glass, along with of fired brick fragments and gravel.

Digging deeper into the western part of the excavation site, closer to the central part of the excavation unit, a cluster of large gravel stones were discovered (Lo. 16) (Fig. 82).

A surface sweep in the southeastern part of the excavation revealed a layer (Lo. 17). The layer was loamy, of average density; its light brown in color. The swept layer contained a small number of fragments of glazed pottery, mostly from thick-walled pots.

Removing the above-mentioned layers and sweeping the surface in the southeastern part of the excavation revealed a loamy yellow layer (Lo. 18). The layer extended from the eastern side of the excavation and narrowed towards the center (Fig. 97). The length of the layer within the excavation along the east-west line measured 5.5 m, width - 3.2 m, thickness - 0.2 m.

Following removal of the yellow loamy layer in the southeastern part of the excavation there was found an accumulation of broken, fired bricks, pottery sherds and animal bones (Fig. 98). The accumulation was circular; its diameter was 0.8 m, and possibly a pit (Lo. 19).

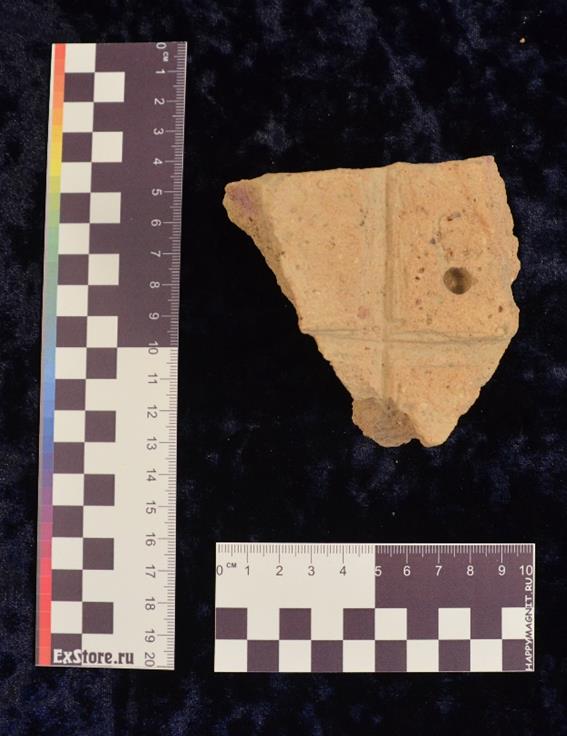

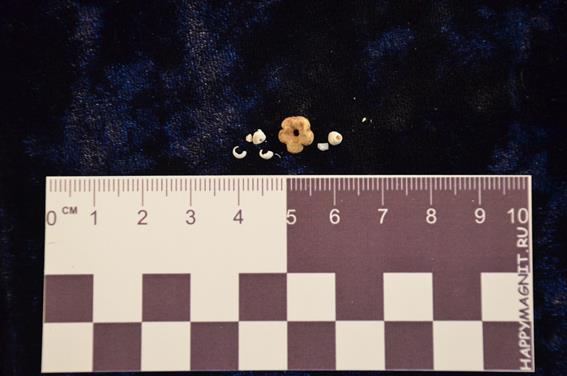

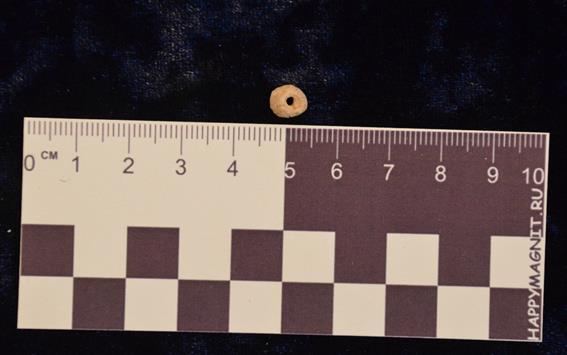

One large amorphous pit was found in the northwestern part of the northern edge of the excavation (Lo. 22). This pit’s diameter was 1.3 m, its depth, 1.2 m (Fig. 101-102). The pit was filled with friable loam. Several pottery fragments were found in the course of clearing this pit. Among some of the more interesting finds, of particular interest, was a fragment of storage pot rim which has a cross carved into it, a cast metal fragment in the form of a plaque, a small glass tube bead, and three small glass fragments.

Two small pits were discovered in the northeastern part of the excavation. Pit no. 4 (Lo. 23) was located 1 m to the southwest of pit no. 2 (Lo. 14), the pit was round (Fig. 103). Its 0.7 m in diameter with a depth of 0.4 m. The pit’s contents contained a friable, loamy soil mixed with ash. The pit revealed several pottery fragments, animal bones and a piece of glass.

1.1 m to the southeast of pit no. 4 another pit (no. 5) was found (Lo. 24). This pit is circularly amorphous with a diameter of 0.7-0.4 m, and a depth of 0.3 m (Fig. 104). In the course of clearing the pit pottery sherds, animal bones and a piece of metal in the form of a curved narrow plate with a hole at the end were found.

Another pit, no. 6 (Lo. 26), was cleared in the southwestern part of the excavation (Fig. 107-108). The pit was oval-shaped, 0.7 m in diameter with a depth of 0.35 m. The pit contained friable soil. The pit’s contents included several pottery fragments, animal bones and fragments from glass vessels.

On the north side of the excavation unit, an expansion unit was dug (excavation expansion unit no. 1.) The expansion unit dimensions were 10 m long in an east-west line with a width of 5 m (Fig. 124-137).

In the eastern part of expansion unit no. 1 pit no. 7 (Lo. 27) was uncovered. The pit was filled with a significant amount of broken, fired bricks, pottery sherds, stones, and gravel (Fig. 141-143). The pit was circular with a diameter of 0.9 m, and depth of 0.4 m (Fig. 144).

In the course of sweeping the surface of expansion unit 1 in its southwestern section there another pit was found. Pit no. 8 (Lo. 28) was round, with a diameter of 1.1 m and a depth of 1.5 m (Fig. 146). The pit’s soil was friable. This pit, unlike the others, contained only a small amount of pottery sherds.

In the northern part of the expansion unit a plot with friable ashen soil was identified which contained a considerable number of pottery sherds and animal bones (Lo. 29). The plot’s dimensions were 3 by 2 m with a thickness of 10-15 cm (Fig. 147-149).

From the east side and toward the center stretched a dense light brown soil layer (Lo. 30). This layer occupied more than half of the area of expansion unit no. 1 (Fig. 150-151). Its southeastern section was penetrated by a small ravine, which stretched from the eastern side in a southwesterly direction.

Another expansion unit (no. 2) of 6 by 4.5 m (Fig. 153-157) was dug off of the main excavation from its southwestern side. A dense layer, a continuation of the Lo. 10, was revealed in the eastern part of the expansion unit no. 2. The layer extended in a westerly direction for an additional 2-2.5 m.

Following removal of the topsoil in the western part of expansion unit another pit was revealed (Lo. 31). Pit no. 9 is circular, its diameter is 1.1 m with a depth - 0.7 m. Pottery sherds and animal bone were found in the pit as well as a metal artifact in the form of small metal tube.

In the southeastern section of the expansion balk another pit was discovered (Lo. 32). Pit no. 10 was oval-shaped with a diameter of 0.7 m and a depth - 0.9 m. Excavations revealed pottery sherds as well as goat and sheep bones.

From the northern section of expansion unit no. 2, another expansion unit was dug (no. 3) with dimensions of 5 by 10 m. Within expansion unit no. 3 no cultural material was found, except in removal of the topsoil layer which yielded many pottery sherds. (Fig. 164-167).

From the western part of expansion units no. 2 and no. 3 another small expansion unit was dug (no. 4). The expansion unit’s dimensions were 5 by 15 m. In the course of topsoil removal many pottery sherds, mainly from large vessels like pots and storage jars were uncovered.

In the northwest corner of this expansion unit an amorphous pit was discovered. Its diameter were 0.6-1.3 m with a depth - 0.4 m. The pit contained friable soil with found many sherds and gravel.

To the north of expansion unit no. 1 another expansion unit, (no. 5) with dimensions of 5 by 10 m was dug. Once again, in the course of topsoil removal a large amount of sherds and animal bones were found.

A ravine was found following the topsoil removal in the southeastern section of the expansion unit 5 (Lo. 35). The ravine was 0.7 m wide and stretched from the eastern side of the excavation in a southwesterly direction.

In the northeastern corner of this unit an area with clay soil was identified (Lo. 36), with inclusions of a mass aggregation of pottery. The shape was rectangular, 2.8 by 1.3 m; with depth of 0.5 m (Fig. 182-183).

In the northwestern part of the expansion unit no. 5 another a clay layer was revealed with a large number of pottery sherds and several medium-sized gravel stones.

In the northeastern section of this excavation a round pit was found with a diameter of 1.4 m and a depth of 0.3 m (Lo. 38). The pit contained friable loamy soil. Clearing revealed pottery sherds and goat and sheep.

In the western part of the main excavation at the edge of the balk, a shrub was removed a small pit was dug in its place. The pit dimensions were 1.2 x 1.2 x 06 m (Fig. 99-100). As a result in reading presence of uniform light-brown loam in the pit profiles.

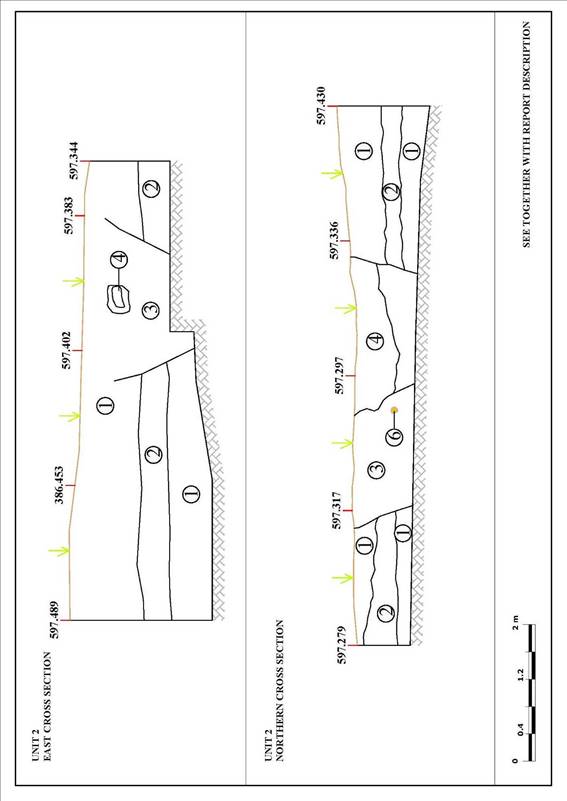

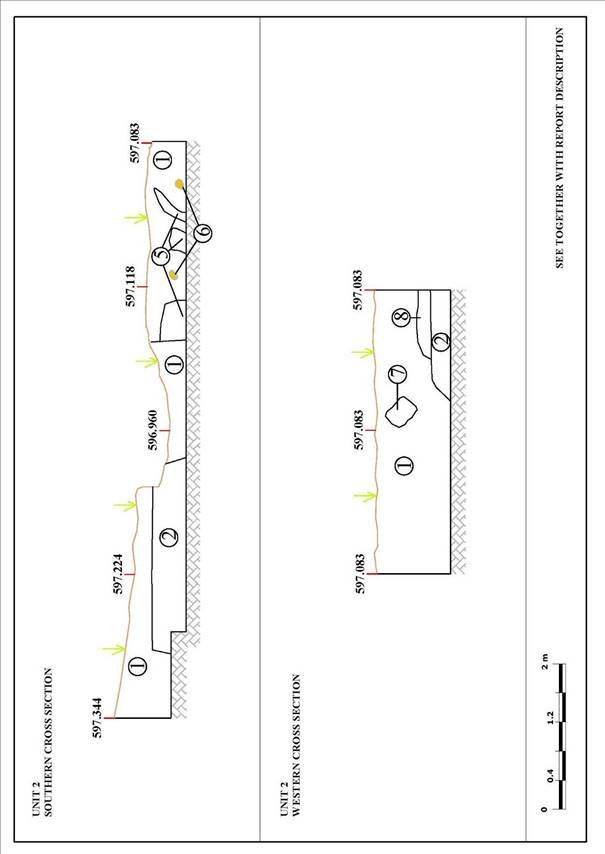

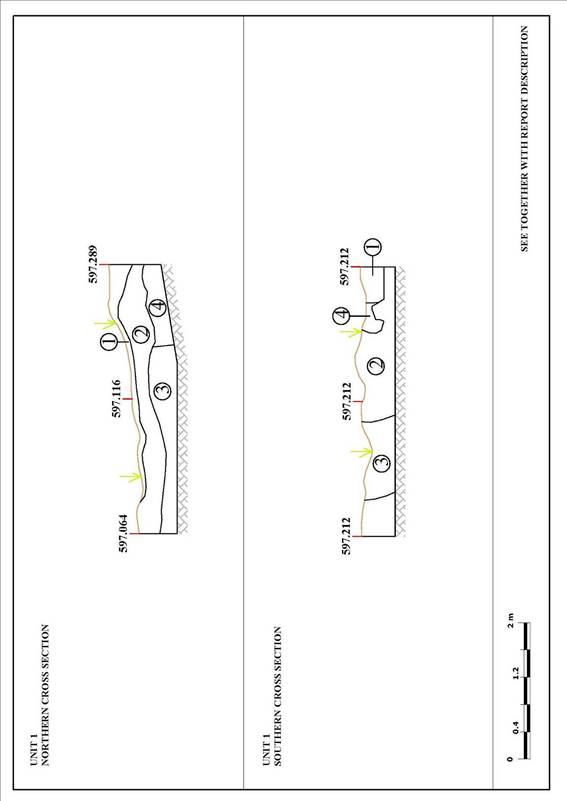

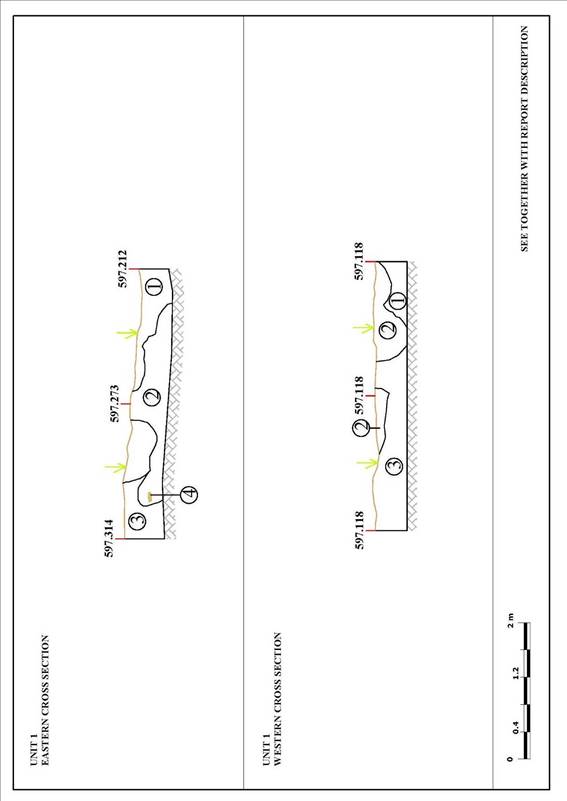

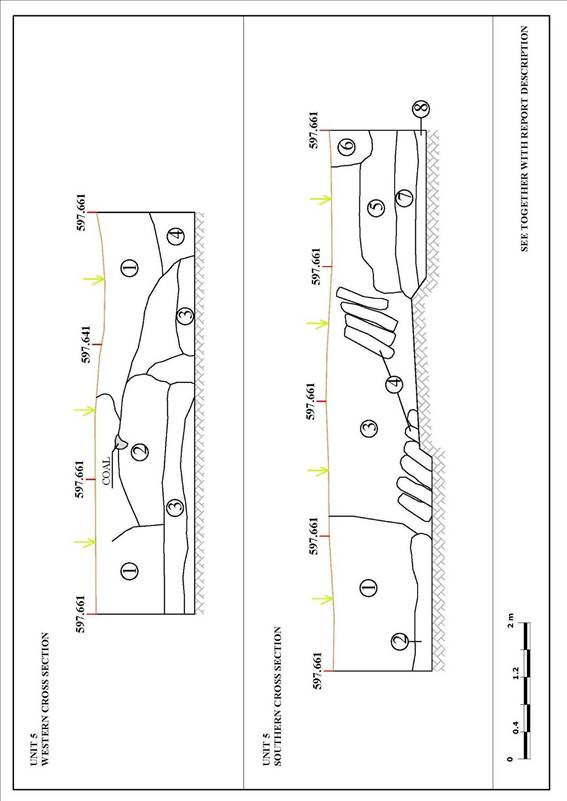

A pit was also dug in the eastern section of the main excavation unit in order to identify the cultural stratigraphic (Fig. 114-126). The size of this pit along the north-south line was 7.5 m, by 2.8 m with a depth of 0.9 m. At a depth of 40 cm from the modern surface a hard, light-brown soil layer was reveal which was sterile of any cultural material. Thus, at a depth below 40 cm is the original surface.(see the Illustration documentation on stratigraphy).

The total area of Excavation 1 was 342.5 m2. The study revealed that the site has a single cultural layer, which, presumably, dates from the beginning of the 12th century. Unfortunately, no distinct structures survived on the site being researched, with only pits being identified with a large number pottery sherds, animal bones, glass shards, one coin, several of manufactured metal, and broken bricks and gravel.

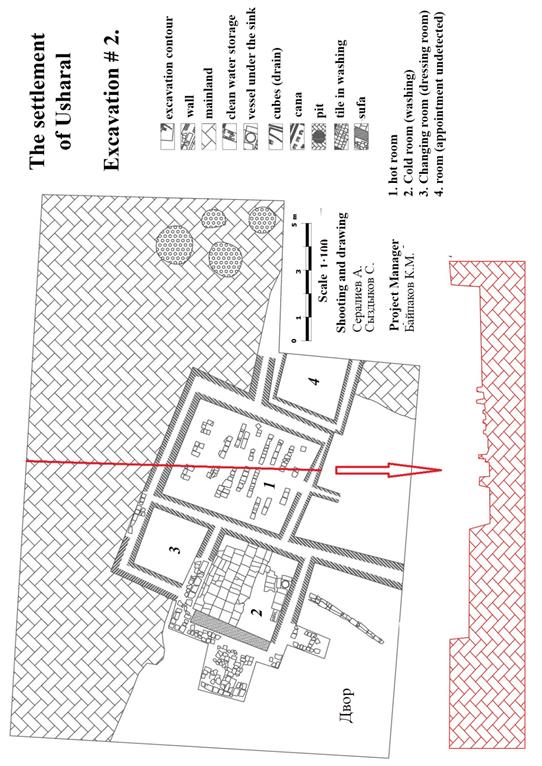

4. EXCAVATION 2

4.1 General overview

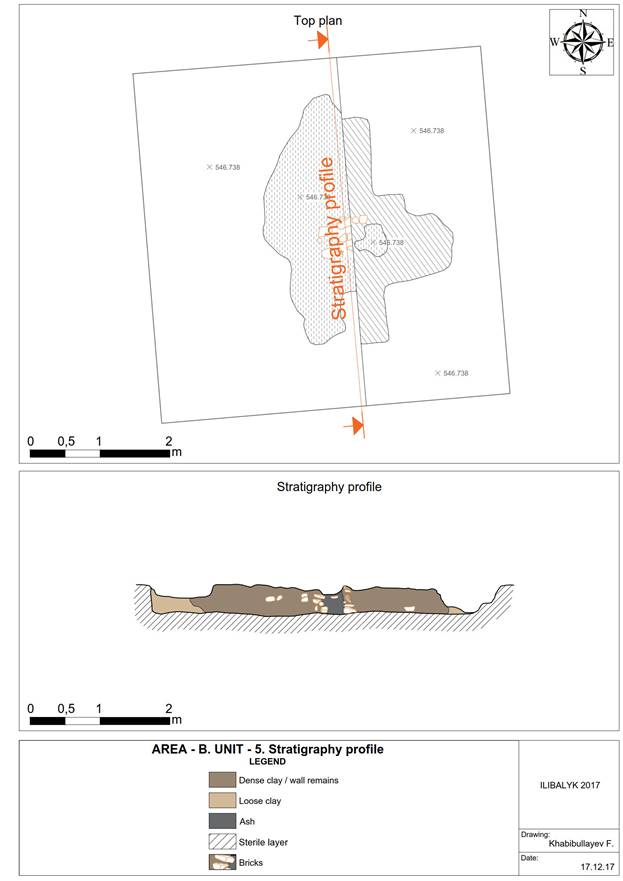

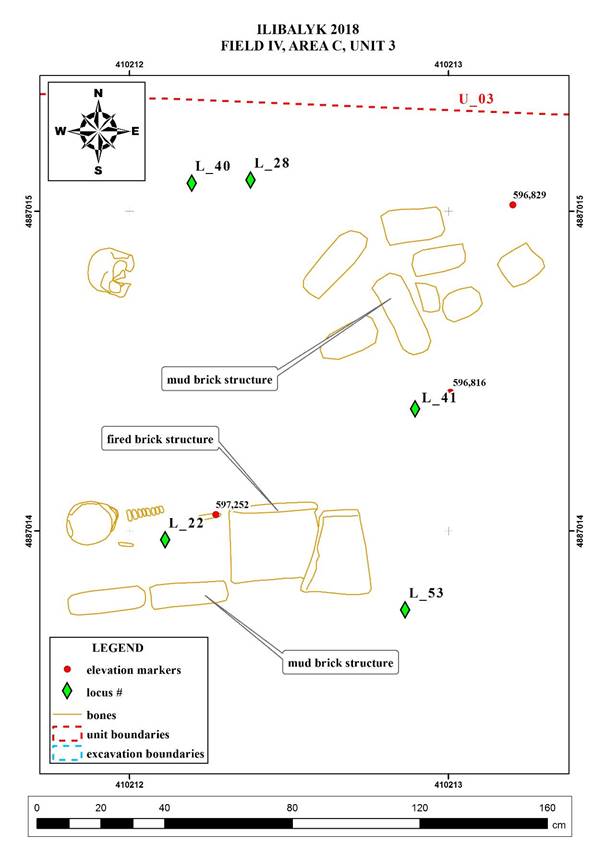

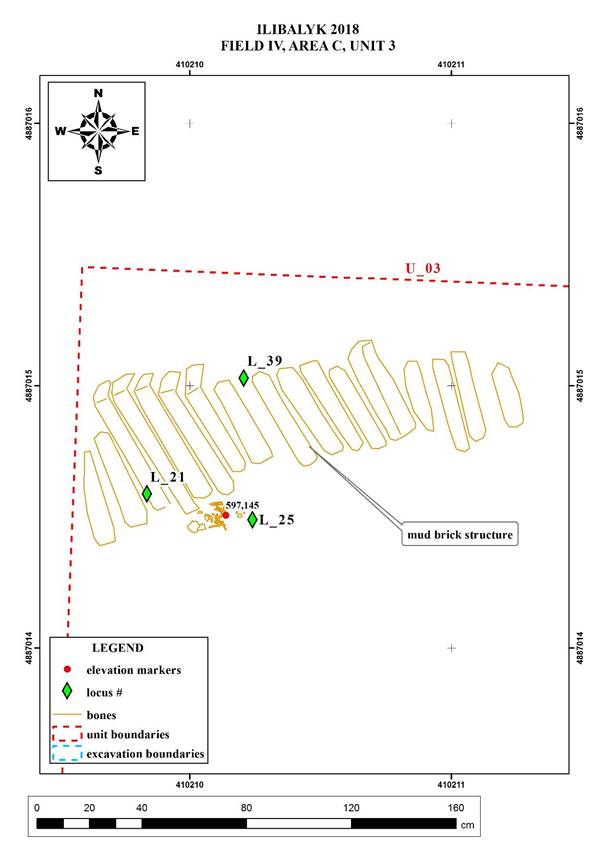

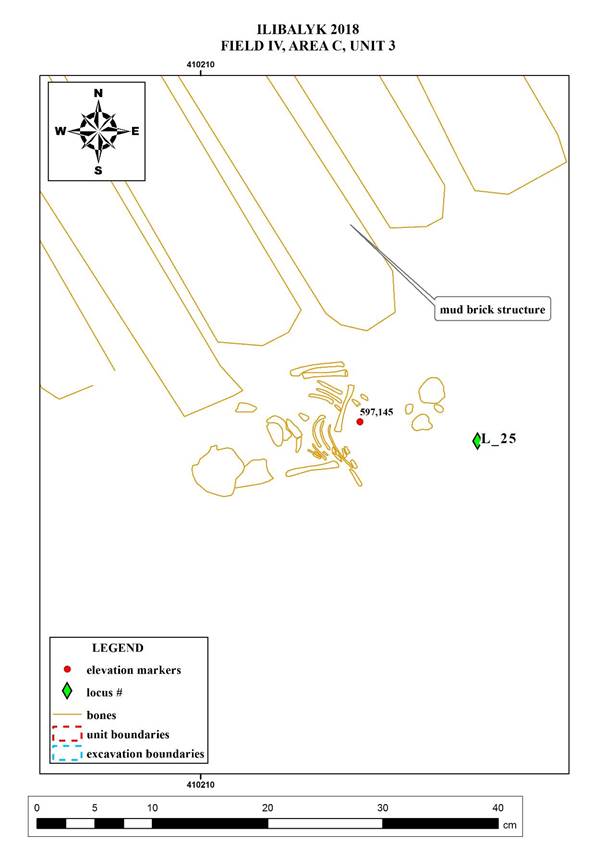

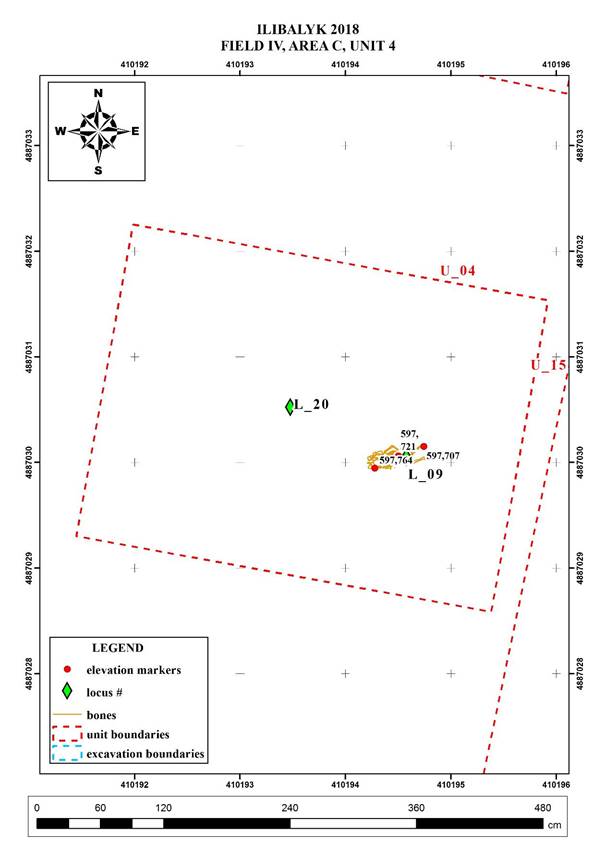

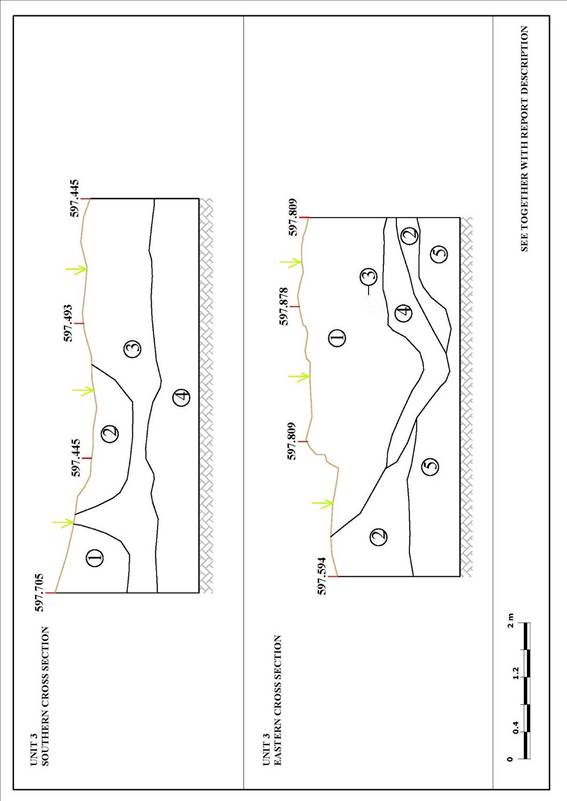

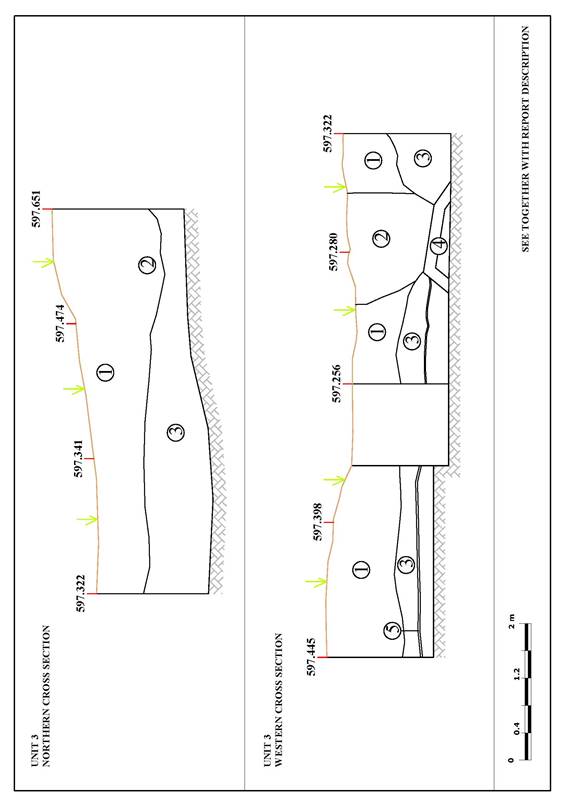

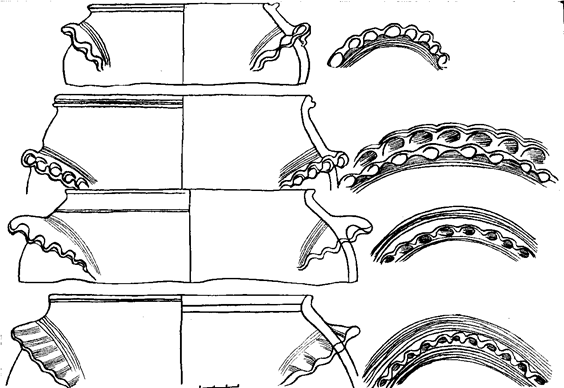

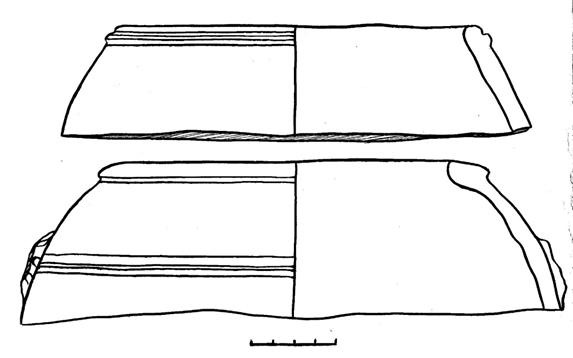

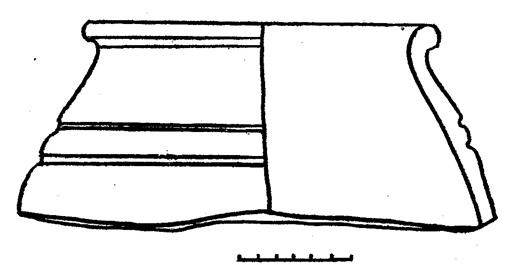

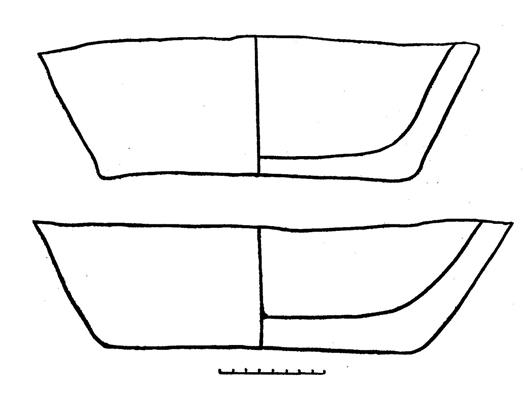

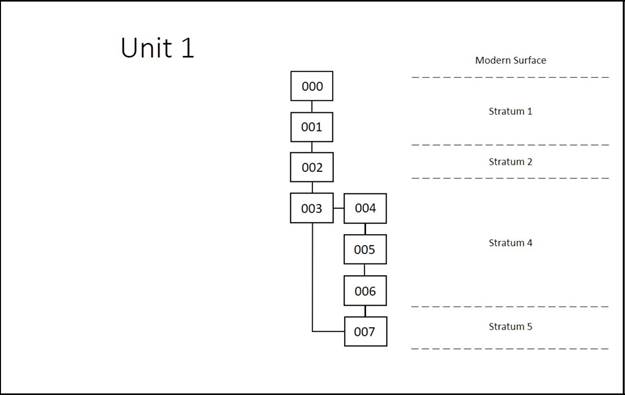

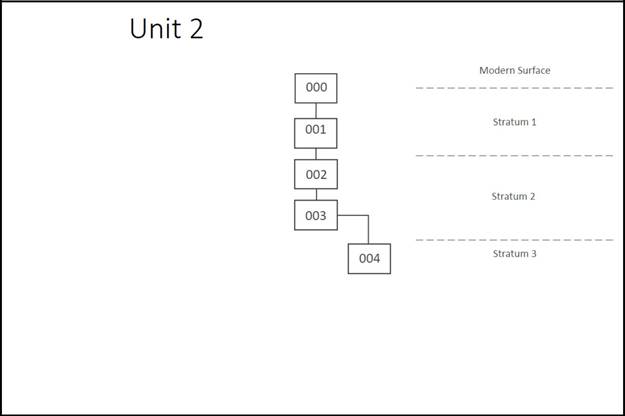

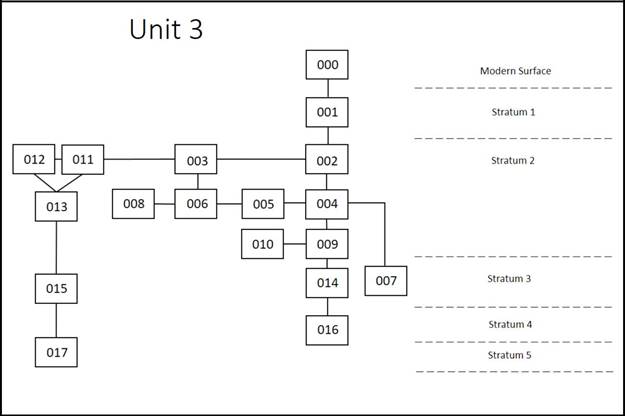

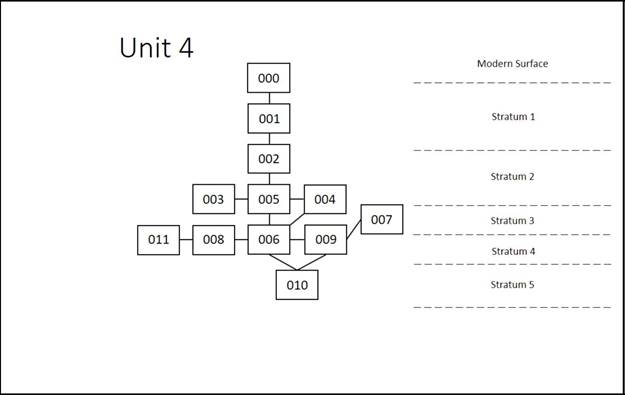

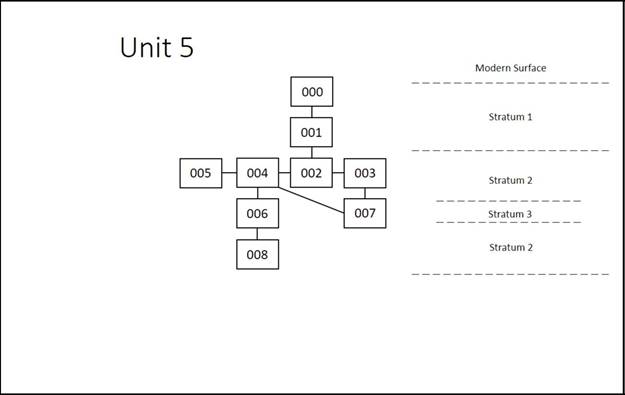

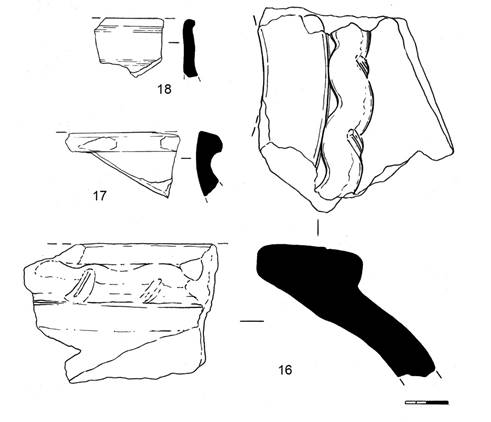

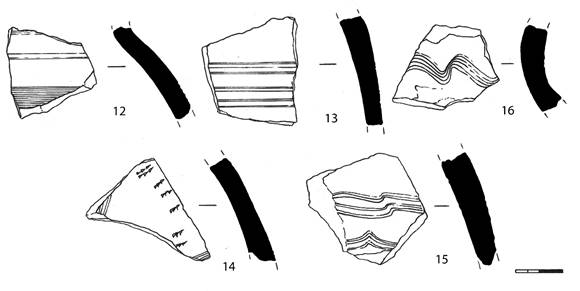

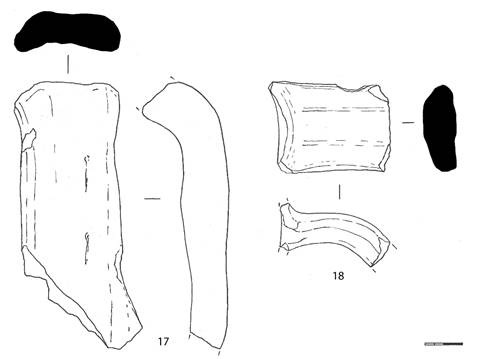

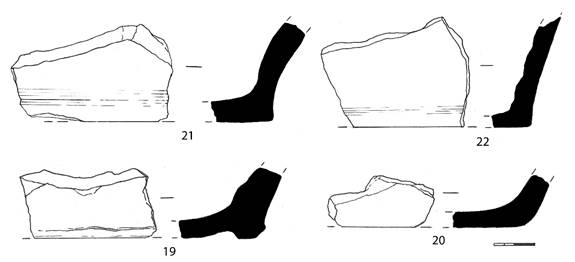

Studies of the second excavation site, which were undertaken on the location of the city’s citadel, identified three construction horizons. Compared to the first excavation site the ceramic material demonstrates, with only a few exceptions, the absence of glazed ceramic fragments. A few well-preserved walls made of mud brick placed in 9 ranges (size of mud bricks were 27x16 cm) were identified in the southern part of the excavation site. Also the territory of the excavation site No. 2 revealed some rubbish pits from the upper construction horizon in its southern and northern corners.

The excavation process identified three construction layers: An upper layer corresponding to the 13-14th century while the second and third corresponding to the 12-13th century.

According

with the data obtained during excavation three general construction phases

(living horizons) were reviled (see below Harris matrix of the excavation 2). The

upper (late) one is correspond to period of abundance with numerous garbage

pits and mad brick debris; second phase shows well preserved architectural

features as well as the earliest (excavated during this field season), which

gave us baked brick constructions, plenty of slags and “kans” (heating system)

usually referenced by the scientists with 13th century.

Aerophoto. Top view. Excavation 2 (area 2)

Aerophoto. Top view. South-east part.

Garbage pits. Excavation 2 (area 2)

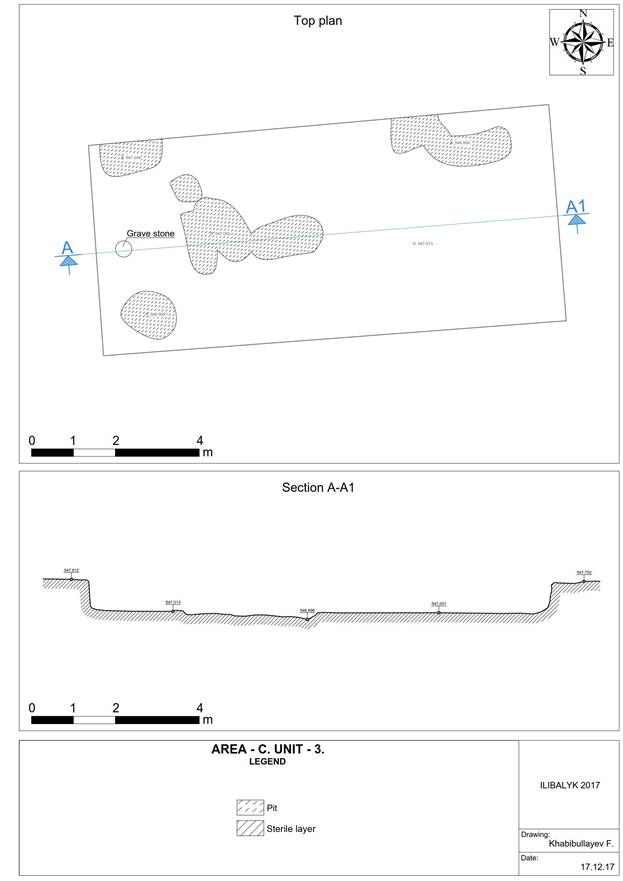

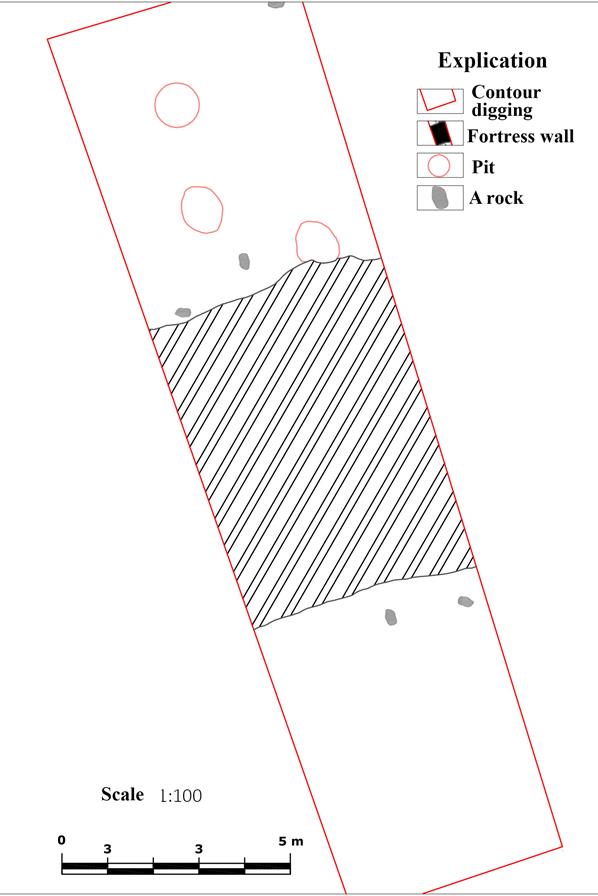

5 . EXCAVATION 3

Excavation

3 Investigations

By

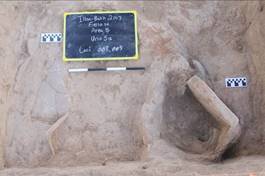

Dr. Tom Davis, Field Director

Associate

Director, Tandy Institute of Archaeology

Ft. Worth, Texas, USA

Ilibalyk August 2016

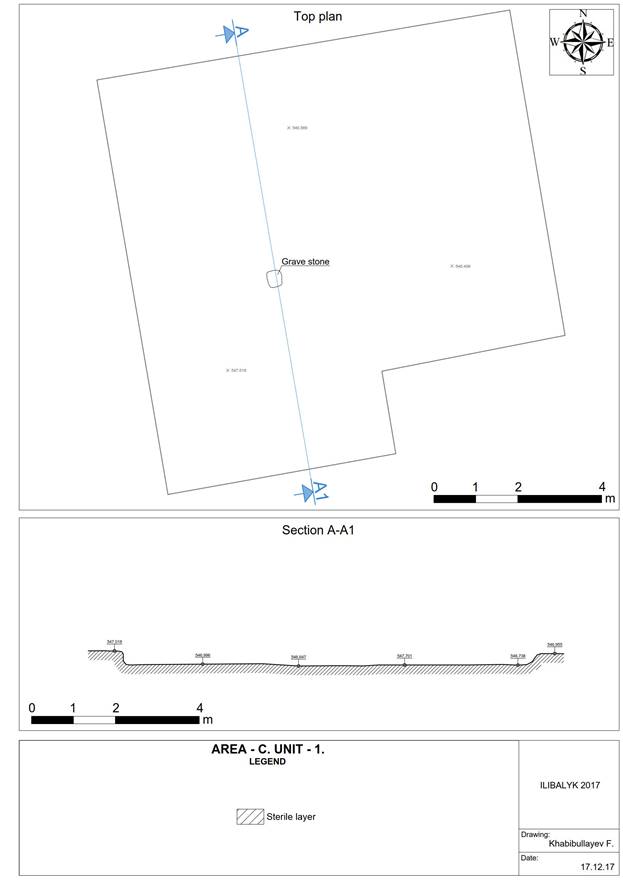

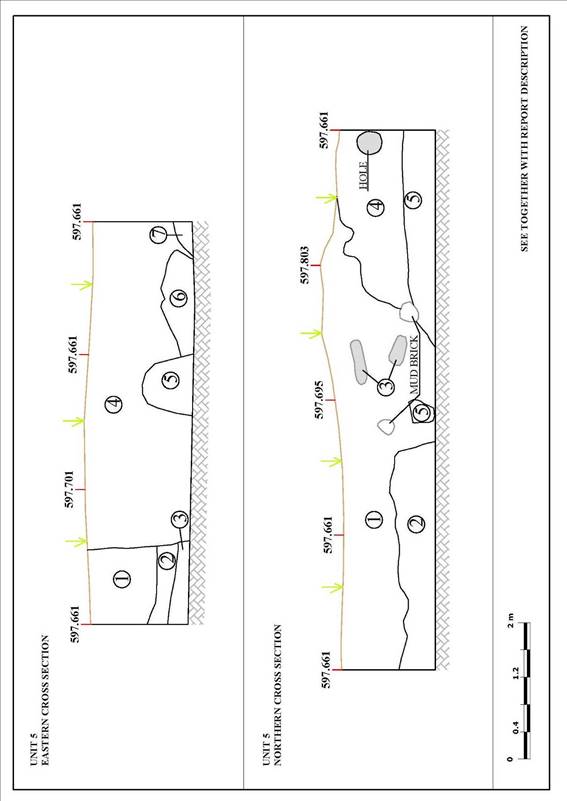

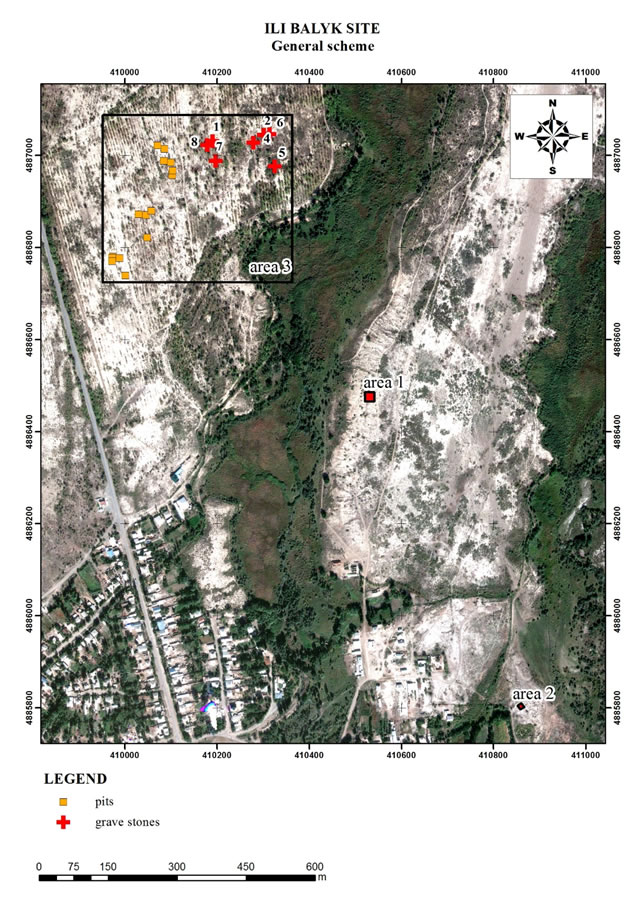

Investigations at Excavation site 3 were undertaken as a direct result of the discovery of a suspected Nestorian grave marker in 2014 near the village of Usharal in eastern Kazakhstan. The Tandy Institute of Archaeology team, in partnership with Archaeological Expertise LLC, and the Society for the Exploration of Eurasia, along witha dedicated team of local volunteers,* undertook a combination of remote-sensing (GPR), limited test excavation, and systematic pedestrian reconnaissance in a successful attempt to provide contextualization for the grave marker, the first clearly identified Nestorian artifact ever recovered within the boundaries of Kazakhstan. The stone marker had been recovered from the surface, reportedly near an overhead transmission line, and taken to the field laboratory of Archaeological Expertise LLC in Talgar, Kazakhstan, near the city of Almaty, Kazakhstan. During the course of the field season, ad hoc informant interviews established that the marker had originally been discovered by a local Usharal resident in an unknown location near the village, and taken into the village in the hopes of using the stone in construction. Upon discovering the inscribed cross, the potential builder decided to abandon the stone and re-deposited it in a relatively open area near a dirt track, NE of the village, allegedly near the original discovery point.

Setting

Excavation site 3 occupies a slight rise of land east of the north/south road linking Usharal and route 353. A low-lying floodplain delineates the landform to the east and south, separating the survey area from the main portion of the archaeological site to the east. Route 353 marked the northern limit of the survey area and the survey area occupies the northern half of the landform. The road lines are marked by planted deciduous trees with the marshy area to the east marked by a few remnant old growth trees. The current vegetation reflects the land tenure history of the area, having been a collective farm from 1930 through 1990. Crops were orchard fruits (primarily apples) and open fields planted in watermelon. The ordered rows of orchard trees are clearly visible on satellite imagery and although many have been uprooted and removed, numerous stumps testify to their former presence. Derelict buildings of the collective farm occupy the northeast of the landform. An overhead Soviet-era powerline crosses north/south from the former collective farm. A dirt track runs roughly parallel to the powerline and provides vehicular access to the property from the Usharal feeder road. The land has since gone out of agricultural use and is utilized by local residents as pasture. The survey team encountered sheep, cattle, and horses on an almost daily basis. Modern dumping episodes litter the landscape, some substantial, including relatively recent house foundation remains of river cobbles, decayed mudbrick and occasional metal fragments. The presence of large numbers of hydrophilic plants testify to the abundant rainfall this year in the region. The undergrowth is relatively open; thistles, thorn and low trees permit adequate surface visibility across more than 90% of the survey area. The area surveyed is bounded on the west by the north-south road into the village of Usharal. The eastern limit of the survey area is the line of a stream, the west bank of which is lined with a dense line of scrub which was not surveyed.

The northern limit of the survey was densely wooded as was the western boundary, these woods giving way to the south and east into the formerly-cultivated fields of the collective. The northwestern limit of the collective was a well-defined field 280m north-south by 170m east-west. Dense thickets of thorns and small trees define the boundaries of this field. The field itself alternated between dense low-thickets of thorns in which visibility was low and relatively sparse grassy areas with good visibility. The remainder of the surveyed area comprised an abandoned orchard. The orchard was overgrown, having a similar pattern of north-south bands of dense thickets of thorns.

Methodology

The survey team designed the field methodology based on the hypothesis that the cross-inscribed stone object marked a Nestorian grave and that its findspot was close to its original location. Dr. Boypakov of the Archaeological Society of Kazahkstan, Dr Voyakin of Archaeological Expertise LLC, Dr. Ortiz and Dr. Davis of the Tandy Institiute, and Dr. Steven Gilbert, a historian based in Almaty and an associate researcher of the Tandy Institute, conducted a field reconnaissance in April 2016. The reconnaissance team established a likely location for the findspot of the inscribed stone near a support for an overhead powerline. The April vegetation was sparse and the ground surface easily visible. Accordingly, the team agreed on a combination of Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR), selective test-unit excavation, and pedestrian reconnaissance as a field strategy.

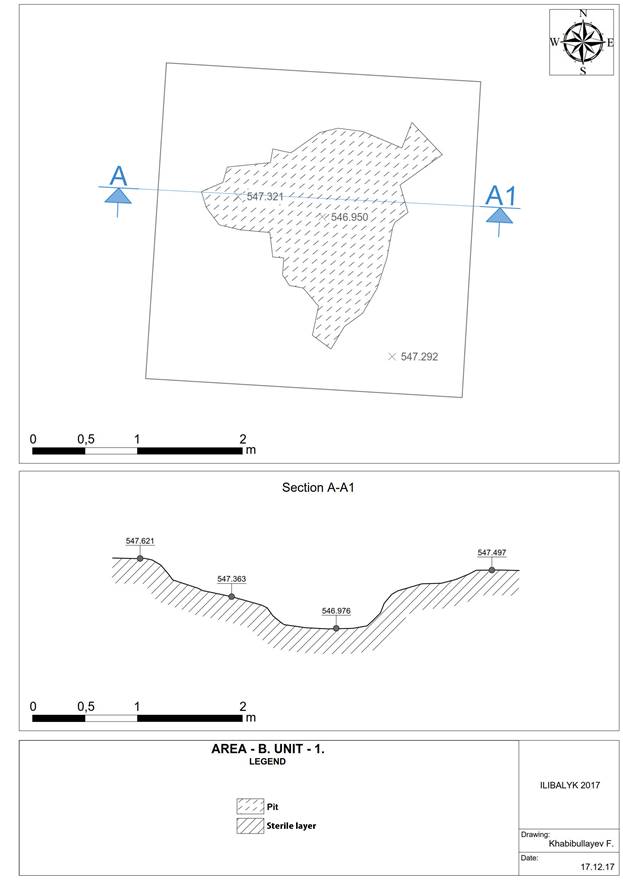

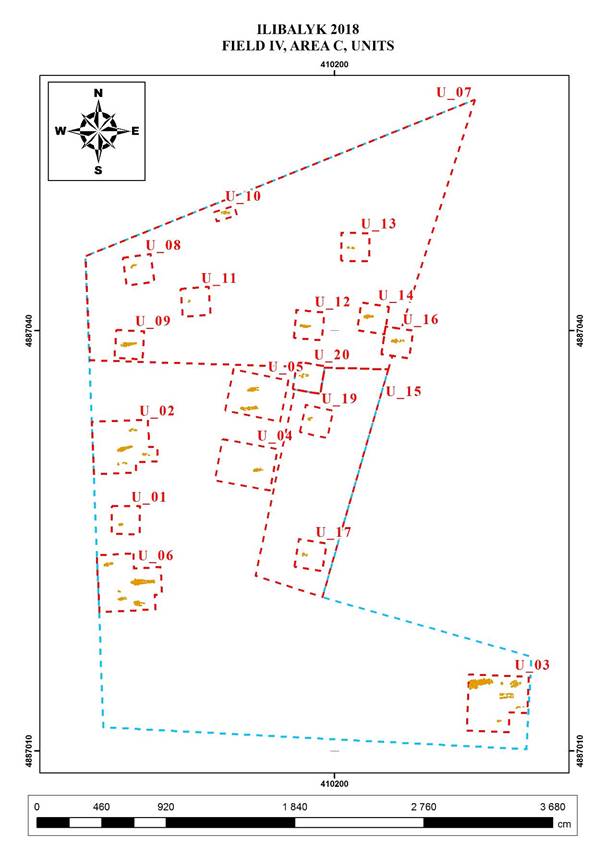

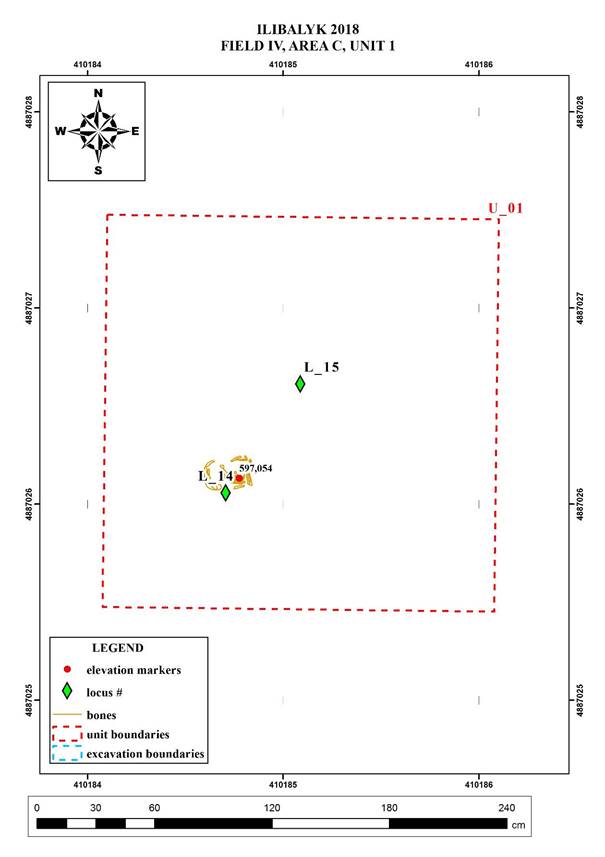

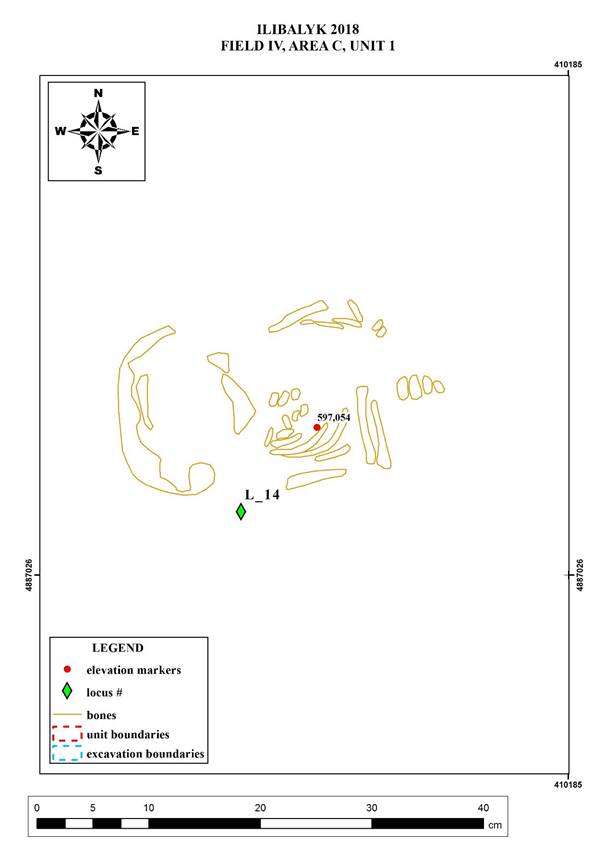

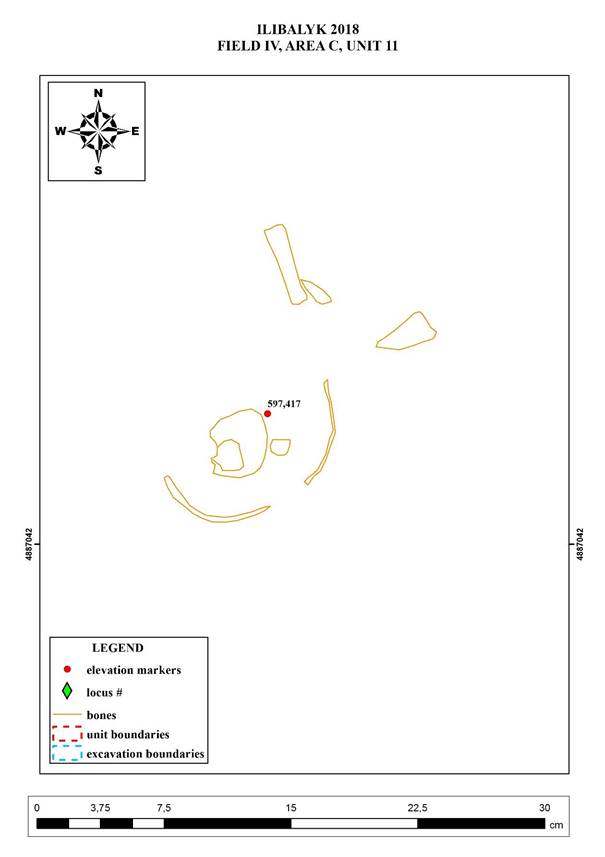

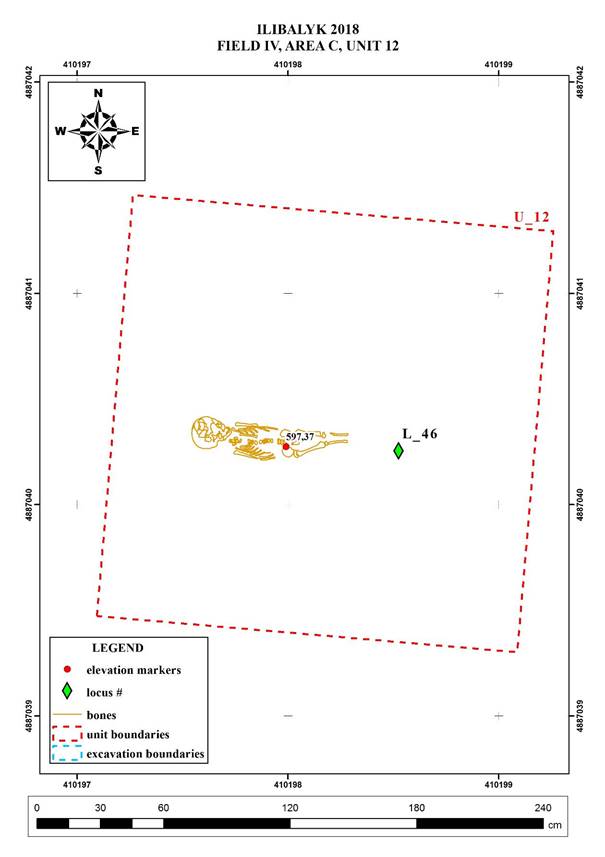

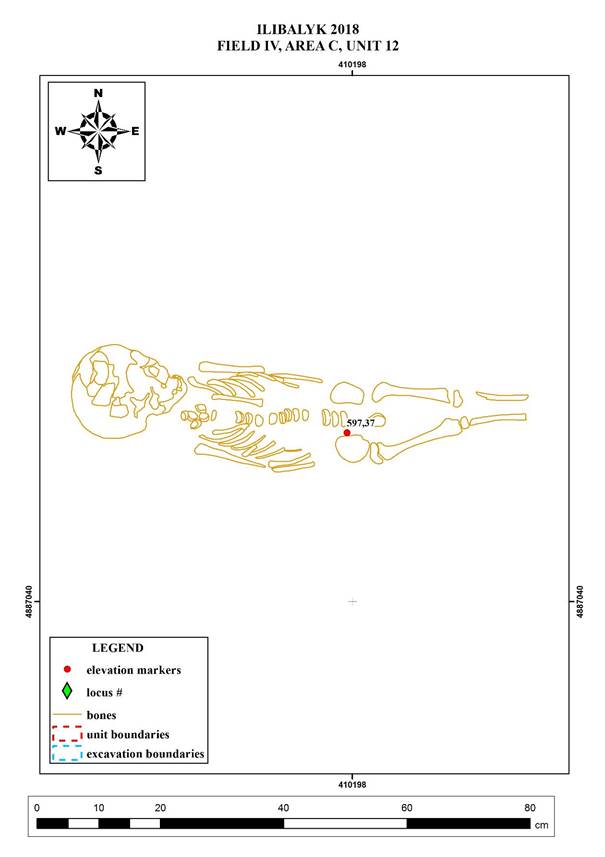

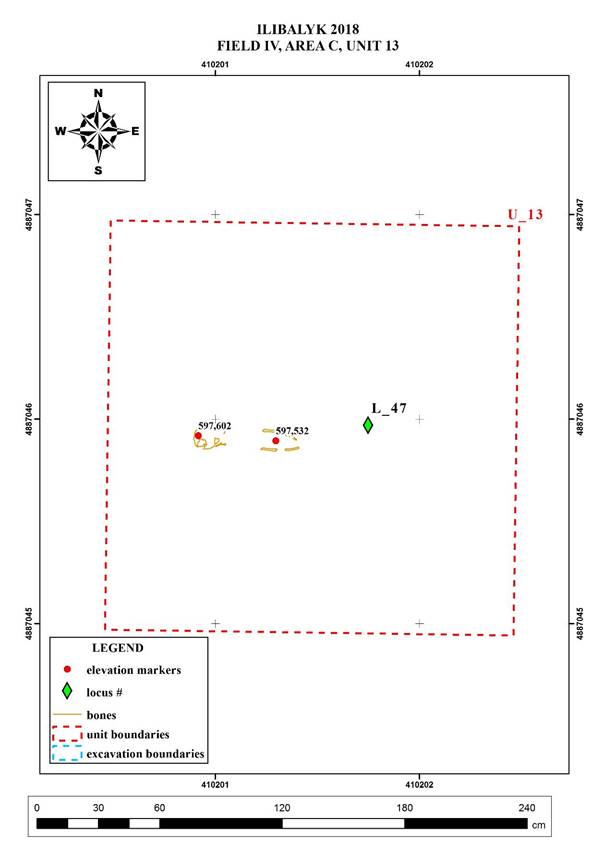

When the main field team arrived on August 1, the wet Spring in the region had substantially increased the ground cover in the proposed test area, limiting GPR examination to a 200x100 m area west of the supposed findspot. (see pages ___ - ___). Initially, the team tested three anomalies revealed by the GPR results using six 1x2 meter units within the anomalies. When these proved negative, the team placed 9 additional 1x2 m units with the placement determined by surface features with some placed near the suspected findspot of the inscribed stone. Field crews excavated the tests using shovel and spades, removing the soil in 20 cm levels within natural stratigraphic layers. Soils were hand sifted in wheelbarrows before being dumped. All test units were excavated at least 10 cms into sterile subsoil or 20 cms below the AB horizon. However, two test units, Unit 11 and Unit 12 were expanded based on the discovery of possible cultural features. The expanded units lead to the excavation of Units 17 through 20, which were larger than 1x2 m.

When the convoluted history of the original carving was relayed to the field team, excavation halted in Field 3 and an intensive surface reconnaissance was undertaken of the entire northern half of the landform. Team members followed transects laid out at 5 meter intervals on a bearing 90 degrees from the Usharal feeder road. Along each transect, Team members examined every visible stone larger than a fist; all were picked up and/or removed from the soil if they extended below the surface. Suspected inscribed stones were examined by the entire team to insure discovery.

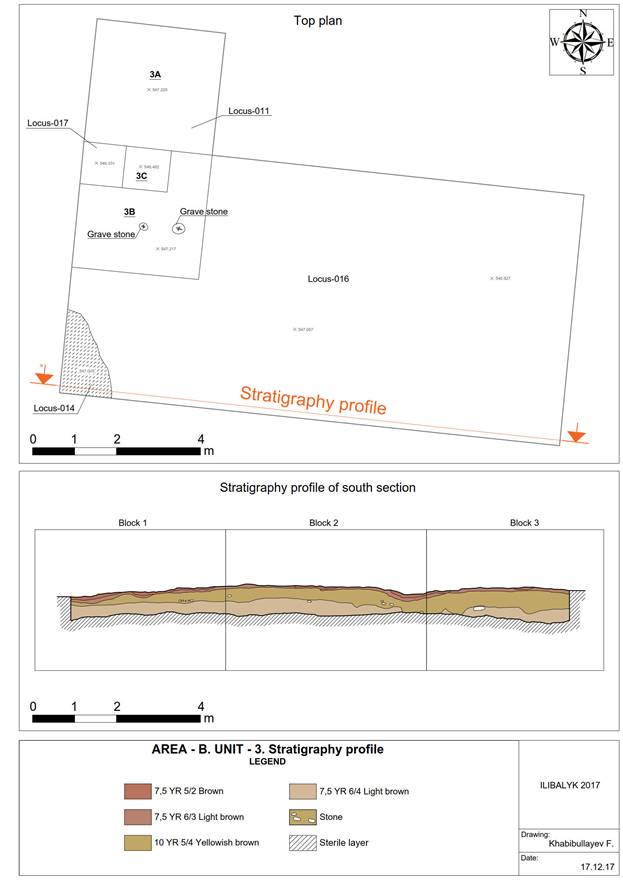

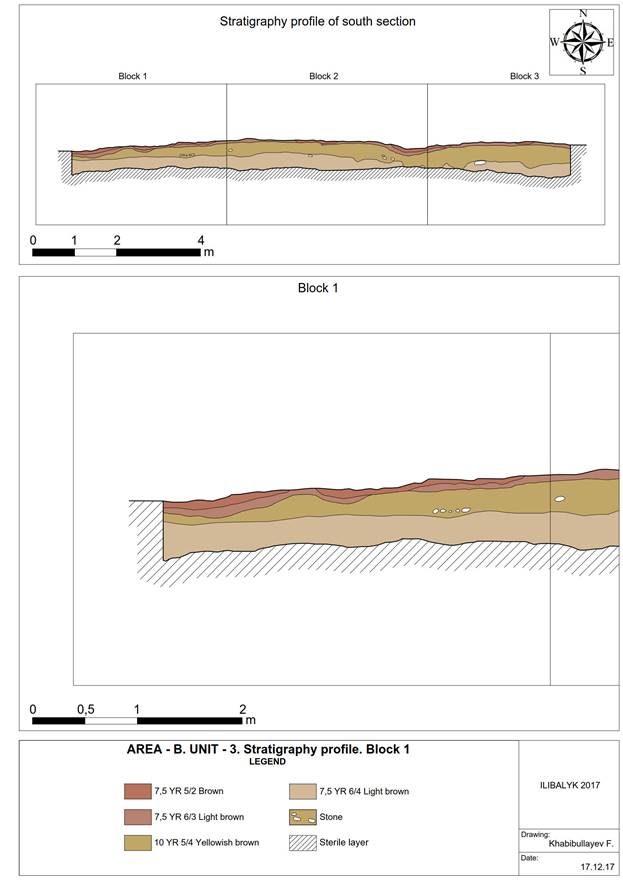

Excavation Results

Excavations

revealed a consistent profile across the initial test area. This plowzone

measured 25 cm deep from the surface, consisting of silty loam, pale brown in

color (10YR 6/3). The second stratum measured between the 25 cm and 40 cm mark

and consisted of silty and sandy clay, and was noticeably more compacted and

dense than the topsoil layer. It was light brownish grey in color (10YR 6/2).

The basal layer measured between the 40 cm and 50 cm mark, which was the usual

end limit of the excavation if no cultural material was encountered. This soil

consisted of mostly clay, mixed with silty soil, and was brownish grey (10YR

6/2). This lower stratum differed from the overlying soil by its density rather

than its difference in color. Due to the lack of artifacts and faunal remains

the filed team decided to cease excavation at the 50 cm level. In the final

phase of each excavation unit, excavators conducted a “compaction test” using

the trowel, noting a uniform density throughout the confines of the trench.

Field 3 survey area

7.3. Field inventory of the finds

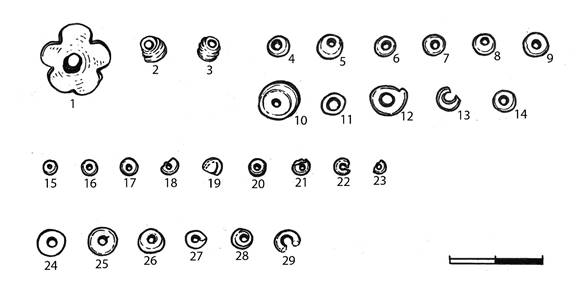

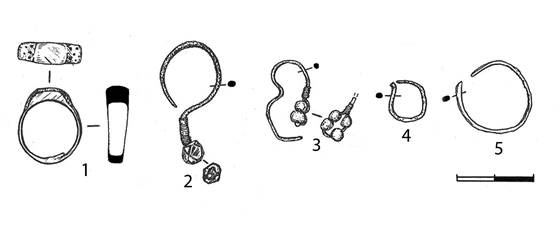

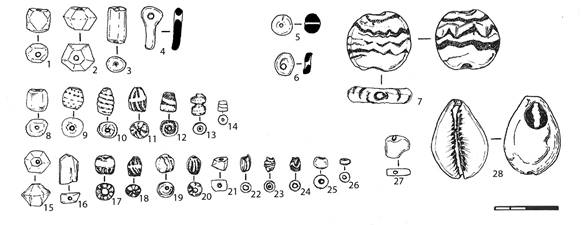

|

21. |

IB-16-3-0-2 Name: Part of a copper basin Dimensions: 33.5х14х0.2 cm. Found 50 m to the north of excavation no. 1 |

|

|

Pottery |

||

|

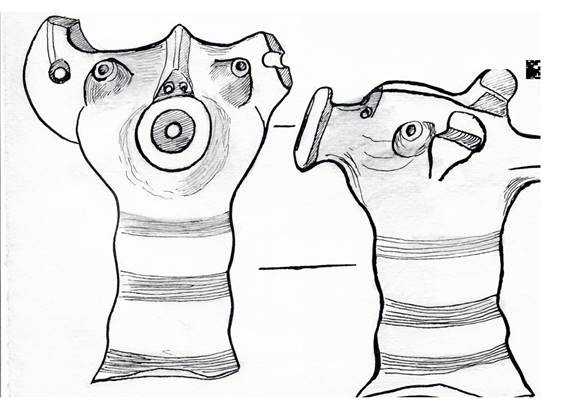

22. |

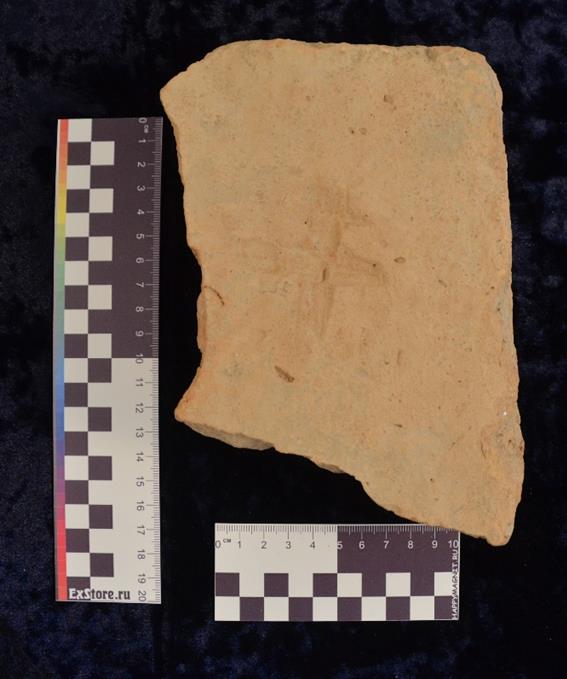

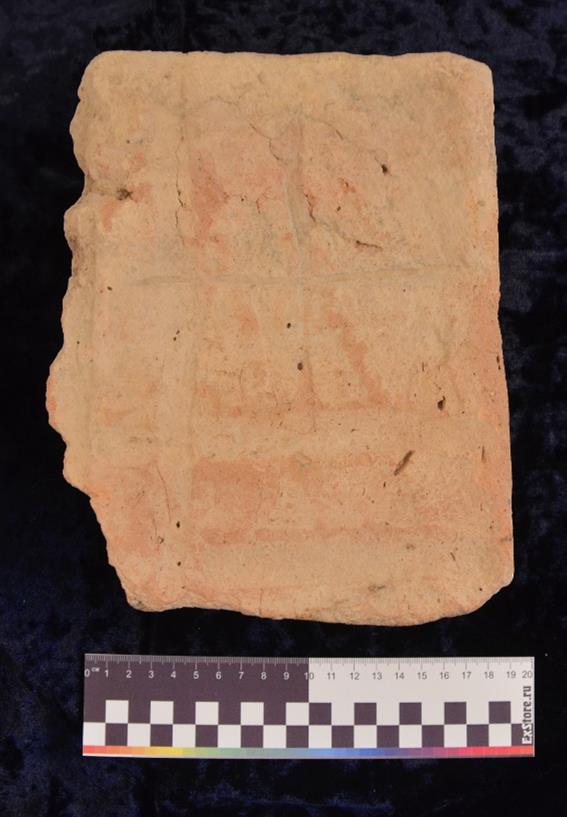

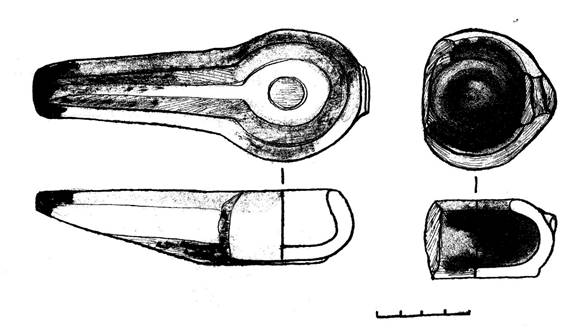

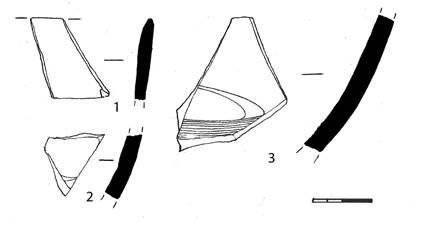

IB-16-2-17-1 Name: ceramic rim fragment. Dimensions: Length- 15 cm Rim’s thickness – 1.9 x 4.5 cm Dimensions of Cross stamps: 1.5x1.5 cm Description: The rim’s cross section is rectangular, its color is a reddish tint with inclusions On the surface there are stamped imprints of crosses enclosed in a circle.

|

|

|

23. |

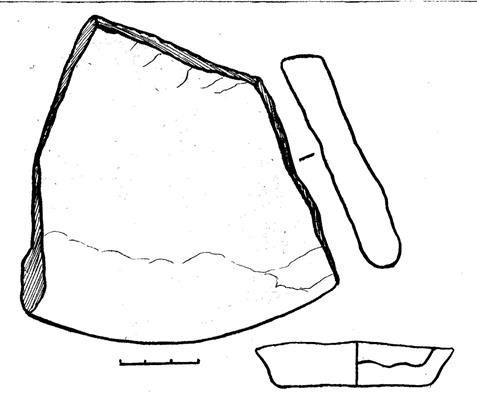

IB-16-1-22-1 Name: ceramic rim fragment. Dimensions: Body of sherd- 1.6 cm. Rim of sherd – 3.3 cm. from top to rim’s edge:3.8 cm. Description: The rim’s cross section is oval-shaped and protrudes outwards as a narrow edge with a flattened outer edge. A light cream-colored slip was applied. The ceramic paste is a reddish tint within the cross section with inclusions. The pot is patterned with a traced figure of a cross. The sherd was found in pit no. 3 (Lo. 22) of excavation no. 1. |

|

|

24. |