| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022/23/24 |

This project deals with the earliest phase of nomadic culture in Aržan (Tuva), the largest and most important site of this

epoch. The 9th/8th century BCE marks the beginning of

profound societal changes which lead to the formation of an aristocratic class

of nomadic horseback warriors. The construction of gigantic funerary structures

with a hitherto unknown richness of grave goods and the inception of the

Scythian animal style reflect these changes in the archaeological record. The

earliest finds of the Eurasian Iron Age were made in the 1970s by M.P. Grjaznov during the excavation of the royal kurgan Aržan I. The transition between the Bronze and the Iron

Age, however, is still hard to grasp and further data is desperately needed to

understand the origins of nomadic culture in Eurasia.

Early

Scythian kurgan Tunnug 1 in Tuva (Photo: K. Chugunov)

Goals

The project

will be led by G. Caspari from University of Sydney as well as S. Pankova and

K. Chugunov from the State Hermitage Museum in St.

Petersburg. During the first field campaign a test trench on the outer border

of a royal kurgan will be excavated where we expect preservation of wood beams

and other organic materials. Samples will be transported to St. Petersburg and

analyzed in the facilities of the Hermitage Museum and the Institute of History

of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Finds remain in Tuva. The

objective is to date the monument and situate it within the broader context of

Eurasian prehistory in Tuva and South Siberia.

The excavated wooden construction under Kurgan Aržan I (Photo: Grjaznov 1980)

Partners

Gino Caspari, Department of Archaeology, Sydney University, Sydney

Svetlana Pankova,

Archaeology of Eastern Europe and Siberia, The State

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Konstantin Chugunov, Archaeology of Eastern Europe and Siberia, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Literature

Chugunov u. a. 2001

K. Chugunov/A. Nagler/H. Parzinger, Der Fürst von Aržan. Ausgrabungen im

skythischen Fürstengrabhügel Aržan 2 in der südsibirischen Republik Tuva.

Antike Welt 32, 2001, 607-614.

Chugunov u. a. 2003

K. Chugunov/H. Parzinger/A. Nagler, Der skythische Fürstengrabhügel von Aržan 2

in Tuva. Vorbericht der russisch-deutschen Ausgrabungen 2000-2002. Eurasia

Antiqua 9, 2003, 113-162.

Grjaznov 1980

M. Grjaznov, Aržan. Zarskii kurgan ranneskifskogo vremeni (Leningrad 1980).

Grjaznov 1984

M. Grjaznov, Der Grosskurgan von Aržan in Tuva, Südsibirien. Materialien zur

Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Archäologie 23 (München 1984).

Report Society for the Exploration of Eurasia

Arzhan 0/Tunnug I – Survey of an early royal kurgan in the Uyuk Valley(Tuva Republic, Russia)

Gino Caspari, Timur Sadikov, Jegor Blochin,2 Maxim Eltsov,2 Katarzyna Langenegger, Trevor Wallace

Highlights

- Survey and test excavations were conducted at one of the earliest Scythian kurgans in Tuva.

- Preserved wood was found at around 40cm depth.

- Preserved wooden beams were found at 100cm depth.

- The kurgan is the largest frozen tomb known to date.

- Other than originally thought, the burial is larger than Arzhan I.

Project preparation

First analyzed and identified through satellite imagery, legendary among archaeologists in Tuva, the gigantic royal kurgan in the swamp along the Uyuk River was the object of this expedition’s interest. A research stay of expedition leader Dr. Gino Caspari in 2016 with the Hermitage Museum and the

Russian Academy of Sciences led to the cooperation and laid the foundation for the project. In fall 2016 the Society for the Exploration of Eurasia pledged a partial financial support which allowed to proceed to the planning phase of the project. Two aerial photos were available from a local Tuvinian pilot, but other than that no maps or other published data was available. In order to gain a better understanding of the site and its surroundings as well as for planning of the logistics, high-resolution satellite imagery was ordered through a grant from the Digital Globe Foundation. Judging from the optical satellite data it appeared clear that there is a radial structure of wooden beams or logs underneath a thick package of stones. The parallels to the royal kurgans Arzhan 1 and Arzhan 5 were apparent, but it was unknown how old the monument is and why it was built in an area which is very untypical for early Scythian kurgans (monuments of this period were usually erected on the river terraces). Arzhan 0/Tunnug I today lies in the middle of a swamp. This led to the following questions:

- How old is the monument?

- What is its place within the cultural development of the Prehistoric Uyuk Valley and in a larger context Tuva and Southern Siberia?

- Why does it lie in the swamp?

- Are there any peripheral monuments near it?

Additionally to the scientific inquiries some practical questions needed to be answered:

- What institutions can be chosen as partners for further cooperation?

- What are the legal requirements?

- What are the logistical problems to excavate this kurgan?

The objectives of the first campaign were to find answers or preliminary explanations for these questions. There was a hope to recover organic material since overall preservation circumstances in Tuva are rather good, however, due to the wetness of the place and changing water levels it was not a given after all.

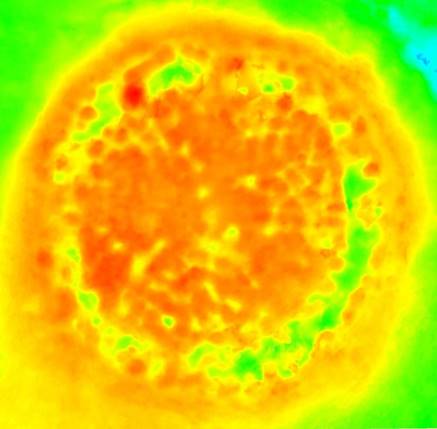

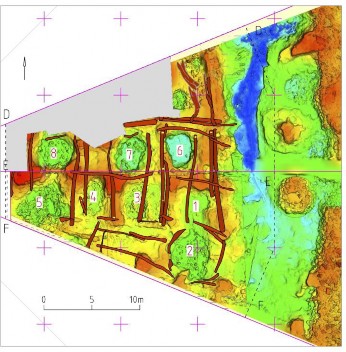

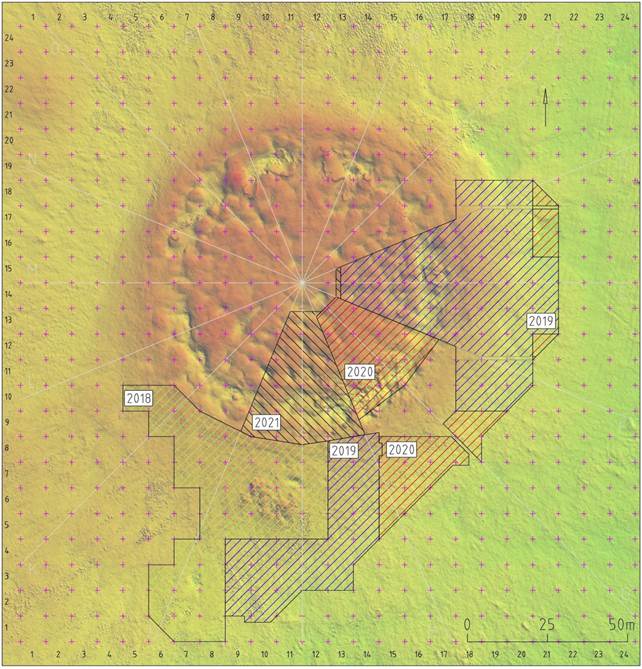

A drone was flown over the burial mound in a regular flight pattern while shooting pictures with 70% overlap. Then a high-resolution 3D-model and ortho-photographs were generated through a structure from motion approach with the software Agisoft. The model has an accuracy of 4cm and was used as the main decision making tool for the further steps of the project. Accurate mapping helped defining the best locations where we would be likely to answer our questions. Figure 1 shows said 3D-model as a heat map. Elevations are displayed as a range of colors from red (high) to blue (low). The radial structure underlying the stone package is clearly visible through the differences in elevation. The deeper parts inside the kurgan (green/yellow) are most likely collapsed wooden chambers which were covered with logs and a layer of stones. The logs broke and the stones fell into the chambers creating stone-filled pits without vegetation. Plants are not growing on top of the pits because the stone package drains the water and no substrate is available.

Figure 1: High-resolution digital elevation model of the monument

Relatively quickly it became clear that we would have to put the site under protection of the local Tuvinian heritage administration and that further excavations will be necessary. We installed 10 ground control points around the kurgan by sinking long wooden poles into the alluvium. The location of the monument and the coordinate system were cross-referenced with known fixed points in the area. With establishing the fixed coordinate system for the site early on, one of the main preparations for future excavation is already finalized and insures exactitude during the coming campaigns.

Walking over the rugged surface of the mound we were able to recognize a large number of vertical stones. These could be from the original structure and were mapped with the total station (theodolite) in order to see if there are obvious patterns emerging without excavation. The map point cloud shows a number of stone cists on top of the kurgan similar to Arzhan I, the points for vertically positioned stones are inconclusive though. The mound appears to be largely untouched apart from a somewhat disturbed periphery because of earlier attempts to source stones for a road through the swamp. It is possible that – because of its hidden position in the swamp – it might be entirely untouched (figure 2).

Figure 2: Rendered ortho-photograph of the burial mound with clearly visible stone pits

The rules established by the Russian Cultural Heritage Administration allow for cleaning of surfaces of covered objects and destroyed parts of structures visible on the surface of not more than around 20m2. Figure 3 shows the areas we decided to work on.

Figure 3: Selected areas for surface cleaning. (J.Blochin)

Area 1

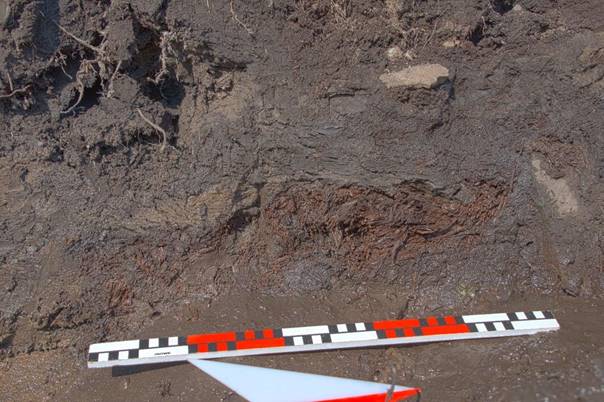

Area 1 yielded the most information (figure 4). It was chosen through the analysis of the 3D-model by looking at pits that seemed to be impacted/destroyed. We cleaned the eroded stones first and cut a clear profile. Only a few centimeters under the surface remains of wood were found.

Figure 4: profile of area II with remains of wood. (K. Langenegger)

At the lower end of the profile the first wooden beams showed up as predicted from the satellite imagery (figure 5). All wood pieces were sampled for further analysis in the laboratory. For control purposes we dug 10cm below the beam and suddenly a layer of gray clay came off the ground. Underneath it the soil was frozen. Measurements with a thermometer quickly let it drop close to the freezing point (figure 6). Cleaning the side profile of area 1 it became apparent that the ice was a regular occurrence at around 1m depth. A test drill in area 2 later showed that the kurgan is fully frozen from one side to the other and thus constitutes the largest frozen tomb in Eurasia.

Figure 5: Preserved wooden beam in the cleaned profile of area 1. (K. Langenegger)

Figure 6: Thermometer on the lower border of area 1 with frozen soil (degrees Fahrenheit), above it preserved wood. (K. Langenegger)

Area 2

Area 2 was set on the western side of the kurgan in the hope of defining the border of the architectural structure (figure 7). In the upper part, the constructive stones were clearly visible on the surface. Unfortunately, the edge seems to be destroyed, therefore the actual size of the object could not be determined through this area. The satellite image provided an explanation: since a palaeo-channel (ancient riverbed) used to flow close to the burial, the shore line might have eroded large parts of the northwestern edge of the kurgan. According to regulations, with a survey license no excavation of the constructive parts of a monument is allowed, therefore we had to stop digging once we reached the stone layer clearly associated with the burial. On top of the stones a number of ceramic fragments were found in a pit. They might date to the 1st cent. AD but only one rim shard was found. Underneath the stone package a number of undistinctive shards were found that might date to the Bronze Age.

Figure 7: drone shot of area 2 with eroded border of the kurgan. (T. Wallace)

With area 3 we tried to determine the outer border of the kurgan by selecting a stone ring (usually a peripheral monument) and cleaning it thoroughly. After the first 20cm it became clear that what we had thought of as stone rings or other peripheral structures were in fact parts of the main structure of the kurgan which had been shifted through taphonomic processes. Area 3 is close to the border of the monument but possible still the original stone construction (possibly also an eroded part, but unlikely so). Using the easternmost edge of area 3 and the center point of the kurgan we can now estimate the original size of the object to about 140m in diameter. This is 30m wider than Arzhan I and makes Arzhan 0 the largest kurgan of its kind in Eurasia. Four bone fragments were found (one of them possibly from a horse). The bones will be taken to the lab for further examination.

Area 4 was opened up along a row of stones in the periphery of the kurgan. The stones proved to have rolled down from the mound and were loosely placed in the soil. Around them only clean grown soil was found under which a light alluvium starts that is void of finds.

Area 5 was a clean area dug outside the periphery of the kurgan with the aim of understanding the geology of the site. Under an upper layer of grown black soil a thick layer of light alluvium was found. In about 1.2m depth a compressed ancient surface was identified. Samples were taken for 14Canalysis. We estimate that this ancient surface is a lot older than the kurgan.

A number of samples were taken (wood, bone, and soil) which will be used for dating and further geological analysis. Especially the clean wooden samples from the constructive wooden beams will provide us with a date for the monument. 14C-dates of bones and the ancient soil will show a range within which to place the construction of the kurgan. Furthermore, soil samples of the profile in area 1 will be analyzed with the following methods:

- grain size analysis

- particle size analysis

- organic carbon analysis

- water extract analysis

- calcium carbonate analysis

- microbiological analysis

- microelements analysis

Results will be communicated once available.

The site lies in a swamp and is hard to reach depending on water levels. Even with a strong tractor it is quite often impossible to get through to the monument (figure 8). Wading through knee-deep swamp we were happy that it is too cold for leeches but swarms of mosquitos and encephalitiscarrying ticks are a nuisance. Logistics of the place are problematic but the monument lies on relatively dry ground and thus can be excavated. The location of the kurgan as well as its state of preservation demand a quick yet carefully planned excavation within the next few years.

Figure 8: Getting stuck in the swamp is a common occurrence. (T. Wallace)

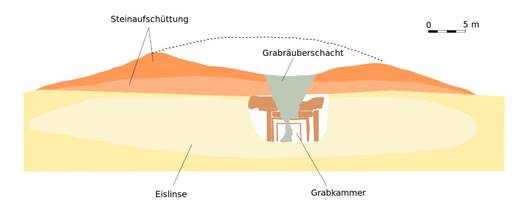

The 2017 expedition to Tuva showed that what was hypothesized via a remote sensing survey can largely be confirmed. Arzhan 0/Tunnug I is a royal kurgan with a structure similar to the earliest Scythian kurgan Arzhan I. Contrary to what was believed before, it is a lot bigger than Arzhan I and possibly older (the dating of the wood samples will bring clarity). It is also the largest frozen kurgan in existence. Similar to frozen kurgans in the Altai region the permafrost is directly below the stone package forming an ice lens (discontinuous permafrost), for the surrounding areas the layer of frozen soil lies a lot deeper. This is exciting because the kurgan will with a very high likelihood yield frozen mummies, horse carcasses, wooden objects, textiles etc. The preservation conditions, age, setting, and size make this monument unique and give it a very high scientific value. No other frozen kurgans of this size are known in Eurasia. It is, however, also a danger because with the global rise in temperature these treasures are in immediate risk of being lost. Large excavation campaigns need to be carried out throughout the next 3 years to excavate the complete object and preserve the knowledge we can gain from it. The planning has already begun.

Figure 9: team in the camp. (T. Wallace)

From left to right, from back to front:

Trevor Wallace: filmmaker

Jegor Blochin: technical lead

Anatolij Luboshnikov: driver

Gino Caspari: expedition leader

Jegor Mazurkievich: cook

Katarzyna Langenegger: volunteer

Maxim Eltsov: soil scientist

Kezhik Mongush: volunteer

Valeria Makarova: volunteer

Timur Sadykov: Russian expedition leader, license holder

Why is Tunnug I/Arzhan 0 a frozen tomb?

Gino Caspari, Frozen tombs have so far been discovered in the Russian, Kazakh, and Mongolian Altai. The most famous one are without any doubt the frozen kurgans of Pazyryk, Tuekta, and Bashadar (Gryaznov 1969; Rudenko 1970). Up until today the finds of Pazyryk are the jewels of the Hermitage Museum and since more than 70 years they are in high demand as exhibit items. Just this year they are again displayed in the British Museum where they serve a fundamental role of showing visitors the enigmatic beauty of Scythian Art.

In the 1990s excavations were conducted on the Ukok Plateau high up in the Russian Altai leading to the discovery of the “Ice Princess” (Polosmak und Seifert 1996). Further frozen tombs were found in eastern Kazakhstan and western Mongolia (Smashev et al. 2000; Parzinger et al. 2008). These archaeological finds gained wide publicity since there is no richer archaeological archive imaginable than if a site has been frozen since 2500 years in the permafrost of southern Siberia. In Pazyryk the oldest carpets were found, wood carvings which look like they were left by someone yesterday, horses with strange adornments of caprid or stag horns, musical instruments and a plethora of other items of which nobody suspected that they existed at the time. Finally, ice mummies revealed more than anything else, how the ancient steppe populations lived and died thousands of years ago. Frozen mummies are extremely rare and most of them will be destroyed by climate change in the near future.

These facts made the discovery of ice underneath the burial Tunnug 1/Arzhan 0 extremely excitng

(see fig. 1). But how do we know that this tomb is frozen? No other frozen tombs are known in the Uyuk Valley. They closest ones were located in Mongun Taiga on over 2000 m asl. and are usually very small tombs without any grave goods. Tunnug 1/Arzhan 0 on the other hand is clearly a princely tomb and lies on 800 m asl.

Fig. 1: Frozen soil underneath the stone layer of Tunnug 1/Arzhan 0.

The thermometer quickly fell to below 40° Fahrenheit (4.5°C) with a surrounding air temperature of 32°C.

Frozen soil was found on several locations underneath the tomb. In the profile of area 1 at around 1.1m of depth and in area 2 at around 0.8m of depth. The reason for this are specific physical circumstances caused through the stone package of the burial mound (see fig. 2). The stones enclose many air pockets which de facto constitute an insulating layer. During summer only the uppermost layer of stones heats up. In winter temperatures in Tuva fall below -50°C and in summer nights can be bitterly cold. The relatively warm days thus do not suffice to melt the ice underneath the burial mound. There is also deeper permafrost in Tuva, known from drillings conducted during the construction of the railway, however, it lies in a depth of around 5-6m and thus underneath the archaeologically relevant layers. Because of this the circumstances around Tunnug 1/Arzhan 0 are referred to as discontinuous permafrost.

Why are there no other ice lenses underneath kurgans in the Uyuk Valley? The reason is the lack of water. Tuva is a relatively dry steppe landscape. All other princely tombs are built on the river terraces and receive little precipitation. Tunnug 1/Arzhan 0 lies in a swamp, therefore water enters the grave and the tomb remains frozen. One exception constitutes the other early Scythian princely tomb Arzhan I which showed extremely well preserved wood. The organic remains in this grave were only preserved because water flowed through the burial (a source used to come up through the grave, hence the name „Arzhan“ which means source in Tuvinian). Materials which decayed more easily than wood were not preserved there.

Fig. 2: The phenomenon of frozen tombs is known from the Altai Mountains.

Water enters the mound and freezes the grave chamber. The physical characteristics of the mound preserve the permafrost of the vicinity.

Tunnug 1/Arzhan 0’s situation is similar to some kurgans of the Altai Mountains. Patches of permafrost underneath stone kurgans can be found there even though the actual permafrost only starts deeper down.

The burials of Pazyryk measured a considerable 30-50m across, however, they pale in comparison to the gigantic kurgan Tunnug 1/Arzhan 0, which is with roughly 140m in diameter one of the largest Scythian graves in Southern Siberia. These circumstances in combination with the ice lens and the fact that it is quite likely the oldest Scythian kurgan in existence is a guarantee for discoveries that will change our understanding of Eurasian Prehistory.

Bibliography

Gryaznov, M. P. 1969. South Siberia. London: Barrie und Jenkins.

Parzinger, H., Molodin, V. and Cėvėėndorž, D. 2008. Das skythenzeitliche Kriegergrab aus Olon-KurinGol: neue Entdeckungen in der Permafrostzone des mongolischen Altaj. Vorbericht der russischdeutsch-mongolischen Expedition im Sommer 2006. Eurasia Antiqua, 14: 241-265.

Polosmak, N. V. and Seifert, M. 1996. Menschen aus dem Eis Siberiens: Neuentdeckte Hügelgräber (Kurgane) im Permafrost des Altai. Antike Welt, 27: 87-108.

Rudenko, S. I. 1970. Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron- Age Horsemen. London: Dent.

Samashev, Z. S., Bazarbaeva, G. A., Zhumabekova, G. S. and Francfort, H.-P. 2000. Le kourgane de Berel' dans l'Altai kazakhstanais. Arts Asiatiques, 55: 5-20.

Short

Report

Society for the Exploration of EurAsia

Campaign Summary 2018 -

Tunnug I

Gino Caspari,[1] Timur Sadikov,[2] Jegor Blochin2

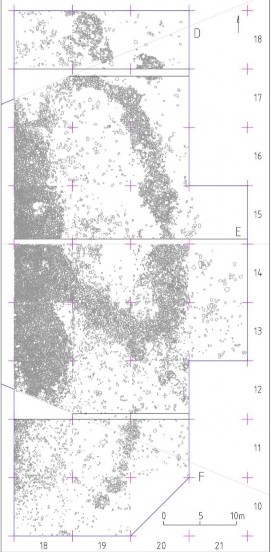

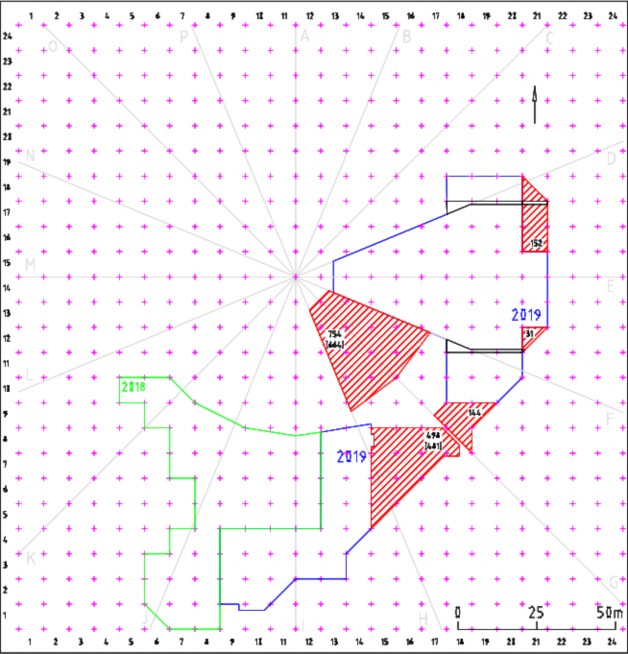

The excavation project at Tunnug 1, which is now the official name of the site, registered with the cultural heritage administration of Russia, was successfully started in late May 2018. The project was led by Dr. Gino Caspari, Timur Sadikov, and Jegor Blochin as in the previous year. The Russian cultural heritage administration required us to excavate at least 2500 m2 of the site. It was the aim of this campaign to understand the southern periphery of the burial mound and define a methodology for the safe and scientifically proper excavation and documentation of this unique monument. We also needed an accurate date for the burial mound, confirming the two existing 14C dates. Furthermore, a camp structure for subsequent campaigns needed to be established.

The excavation turned out to be a lot more complicated than we first thought. In accordance with other royal Scythian burial mounds in the Uyuk Valley, we expected a number of structures from a similar time period in the southern periphery, where our drone mapping indicated that we had to expect at least one larger buried stone structure. A grid of 8m x 8m squares was established for the periphery and we managed to uncover 41 squares (2624 m2). To our surprise, we found Bronze Age ceramics from the Okuneva period, iron arrowheads and belt buckles from the Turkic period, Iron Age arrow heads of late Scythian time, and 21 skeletons most of them likely dating to the early medieval period (Kokel culture). It thus became clear that the site is a lot more extensive than we previously thought. We find remains of all Prehistoric cultures of Tuva starting from the middle Bronze Age.

The first major problem we had to deal with is very strong cryoturbation which mixes up layers and makes the soil very difficult to read and document. In some cases, we had a stone structure on the surface which was shifted more than a meter to the side and effectively not covering the burial pit anymore. The second issue was related to heavy rainfalls. Tuva is usually a rather dry place, but this summer we were hit with two weeks of daily rain and sometimes hailstorms. Our trenches were flooded, and our supply lines were cut. We lost a lot of time due to these circumstances and were not able to finish two low-lying peripheral kurgans with deep chambers, which promise to yield excellent organic remains (permafrost in August lies on 1.5m below ground in areas without stones). The water made it impossible to document the pits and we had to conserve them at the end of August, to wait for a drier period next year. In the burial mound of one of these kurgans we found a very early Scythian mirror and some ceramic fragments, which might date to the same period.

The

finances for the 2019 excavation are already in place. We were able to

establish a camp structure infrastructure which allows us to work efficiently.

We were able to define a suitable methodology for next year’s campaign.

Geophysical surveying would be a great help for planning the next steps and is

thus being implemented at the beginning of the next campaign.

We recovered well-preserved wood from the construction of the main

burial mound. The log was sampled and we were able to count a total of 61 tree

rings. This provides a very good basis for wiggle-matching and receiving an

accurate date for the construction of Tunnug 1. The full report will be made

available after the article about the field campaign currently under review at

the journal Antiquity has been published.

Figure 1: The site with the excavated southern periphery. The two kurgans in the south are clearly visible. The trenches were completely filled with water after heavy rainstorms. Excavating the southern kurgans without heavy-duty pumps will not be possible.

Figure 2: Quadrants at the border of the main burial mound. The cleaning and documentation of the stones takes a lot of time. On top of the stone surface, the majority of the skeletons was found, barely covered with soil. This situation is unknown and requires further investigation.

Figure 3: We established camp on an elevated part in the Uyuk Valley flood plain. A traditional yurt serves as the office and meeting place. We built a sauna close to Uyuk river which replaces showers.

Figure 4: Trenches completely filled with water, a common occurrence and major problem during the first campaign at Tunnug 1.

Figure 5: The team of archaeologists with Explorers Club Flag #134 held by Dr. Gino Caspari.

Short

Report

Society for the Exploration of EurAsia

Campaign Summary 2018 -

Tunnug I

Gino Caspari,[1] Timur Sadikov,[2] Jegor Blochin2

The excavation project at Tunnug 1, which is now the official name of the site, registered with the cultural heritage administration of Russia, was successfully started in late May 2018. The project was led by Dr. Gino Caspari, Timur Sadikov, and Jegor Blochin as in the previous year. The Russian cultural heritage administration required us to excavate at least 2500 m2 of the site. It was the aim of this campaign to understand the southern periphery of the burial mound and define a methodology for the safe and scientifically proper excavation and documentation of this unique monument. We also needed an accurate date for the burial mound, confirming the two existing 14C dates. Furthermore, a camp structure for subsequent campaigns needed to be established.

The excavation turned out to be a lot more complicated than we first thought. In accordance with other royal Scythian burial mounds in the Uyuk Valley, we expected a number of structures from a similar time period in the southern periphery, where our drone mapping indicated that we had to expect at least one larger buried stone structure. A grid of 8m x 8m squares was established for the periphery and we managed to uncover 41 squares (2624 m2). To our surprise, we found Bronze Age ceramics from the Okuneva period, iron arrowheads and belt buckles from the Turkic period, Iron Age arrow heads of late Scythian time, and 21 skeletons most of them likely dating to the early medieval period (Kokel culture). It thus became clear that the site is a lot more extensive than we previously thought. We find remains of all Prehistoric cultures of Tuva starting from the middle Bronze Age.

The first major problem we had to deal with is very strong cryoturbation which mixes up layers and makes the soil very difficult to read and document. In some cases, we had a stone structure on the surface which was shifted more than a meter to the side and effectively not covering the burial pit anymore. The second issue was related to heavy rainfalls. Tuva is usually a rather dry place, but this summer we were hit with two weeks of daily rain and sometimes hailstorms. Our trenches were flooded, and our supply lines were cut. We lost a lot of time due to these circumstances and were not able to finish two low-lying peripheral kurgans with deep chambers, which promise to yield excellent organic remains (permafrost in August lies on 1.5m below ground in areas without stones). The water made it impossible to document the pits and we had to conserve them at the end of August, to wait for a drier period next year. In the burial mound of one of these kurgans we found a very early Scythian mirror and some ceramic fragments, which might date to the same period.

The

finances for the 2019 excavation are already in place. We were able to

establish a camp structure infrastructure which allows us to work efficiently.

We were able to define a suitable methodology for next year’s campaign.

Geophysical surveying would be a great help for planning the next steps and is

thus being implemented at the beginning of the next campaign.

We recovered well-preserved wood from the construction of the main

burial mound. The log was sampled and we were able to count a total of 61 tree

rings. This provides a very good basis for wiggle-matching and receiving an

accurate date for the construction of Tunnug 1. The full report will be made

available after the article about the field campaign currently under review at

the journal Antiquity has been published.

Figure 1: The site with the excavated southern periphery. The two kurgans in the south are clearly visible. The trenches were completely filled with water after heavy rainstorms. Excavating the southern kurgans without heavy-duty pumps will not be possible.

Figure 2: Quadrants at the border of the main burial mound. The cleaning and documentation of the stones takes a lot of time. On top of the stone surface, the majority of the skeletons was found, barely covered with soil. This situation is unknown and requires further investigation.

Figure 3: We established camp on an elevated part in the Uyuk Valley flood plain. A traditional yurt serves as the office and meeting place. We built a sauna close to Uyuk river which replaces showers.

Figure 4: Trenches completely filled with water, a common occurrence and major problem during the first campaign at Tunnug 1.

Figure 5: The team of archaeologists with Explorers Club Flag #134 held by Dr. Gino Caspari.

Society for the Exploration of EurAsia

Campaign Summary 2019 - Tunnug I

Authors and Excavation Lead

Gino Caspari, Timur Sadykov, Jegor Blochin

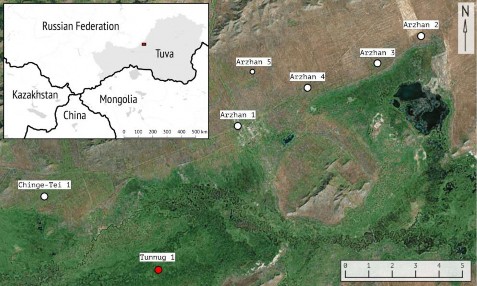

- Fig. 1. Map of the “Valley of the Kings” in Tuva Republic, Russian Federation. Most important burial mounds indicated. Tunnug 1 is the only large burial mound on the southern river terrace.

- Brief Project Introduction

The Early Iron Age in the Eurasian steppes marks the beginning of the appearance of fully mobile pastoralist groups and a steeply hierarchical society with a social elite of warriors fighting from horseback. The circumstances and reasons for its inception are the topic of a hot debate. For the first time in the history of the Eurasian continent, a largely coherent material culture spread from Mongolia to Eastern Europe within only a few generations. The earliest remains of this archaeological culture - defined by the “Scythian triad,” consisting of an assemblage of horse gear, weapons, and items decorated in animal style - are found in Tuva Republic, southern Siberia. Large Early Iron Age burial mounds are plentiful on the river terraces of the Uyuk Valley in Tuva Republic, hence it has been dubbed the Siberian “Valley of the Kings”. The area is widely assumed to have played a key roles in the formation of Early Nomadic societies of the Eurasian steppes. Scythian material culture in Tuva is divided into three periods: An early Arzhan stage (9th/8th century BCE) followed by the Aldy-Bel stage (7th – 6th century BCE) leading into the Uyuk-Sagalyn period (5th to 3rd century BCE). Despite the archaeological documentation of many Iron Age burial mounds in Tuva, the large tomb Arzhan 1 remained the only archaeological monument dating to the formative period of “Scythian” material culture at the end of the 9th / beginning of the 8th century BCE and effectively defined an entire period by itself. In 2014 a much smaller burial mound with around 50 m diameter was excavated (Arzhan 5) which through architectural and stylistic parallels of its objects seemed to date to a similar period. Only in 2017, a first survey at the royal burial mound Tunnug 1 established that this tomb was the earliest known so far. The monument was first analyzed through WorldView-2 data, before a field campaign generated a high-resolution 3D-model and recovered first samples of preserved wood.

The key position Tunnug 1 takes within the chronology of the Early Iron Age steppes has since led to the establishment of a large excavation project. Due to the size of the burial mound and its periphery it is difficult to get a first overview over the extensive funerary architectural complex and – even though necessary – excavation is slow and tedious under the Siberian environmental circumstances. The burial mound’s location within a swamp leads to irregular vegetation growth and an overall difficult readability of vegetation marks. Freezing soil, cryo- and bioturbation complicate the stratigraphy. In order to generate an overview over the site and its surroundings it was thus necessary to integrate a number of data sources to generate a holistic picture of the buried funerary architecture. We were looking to answer the question whether we can detect additional peripheral monuments, later destructions of parts of the burial mound, or internal architectural structures. This led to the publication of a paper in the journal Sensors in 2019 Caspari, G., Sadykov, T., Blochin, J., Buess, M., Nieberle, M., & Balz, T. (2019). Integrating remote sensing and geophysics for exploring early nomadic funerary architecture in the “siberian valley of the kings”. Sensors, 19(14), 3074.The archaeological site Tunnug 1 consists of several parts which can be distinguished as logical spatial units.

-

main mound built of wood, clay and stone

-

the surrounding “gallery” with clay structures

-

a wall surrounding the gallery, made of stone tiles

-

pits going under the wall from the inside (from the gallery)

-

stone rings and layouts surrounding the complex in a whole

-

a large burial mound and some smaller structures dating back to the beginning of our era, partially destroying stone rings

and the edge of a stone wall, especially on the southern periphery of the monumentj. a medieval burial field south of the mound

h. some finds related to the Middle Bronze Age

By the end of the field season of 2019, these parts have been studied to varying degrees. The structures of the beginning of our era, like medieval ones, have been excavated completely. The study of the main, early Scythian component of the monument is just beginning, no more than one-eighth of the area of the main barrow, gallery, wall, stone layouts and rings has been investigated. However, the very first results on a wide area turned out to be extremely interesting We are already able to provide new important arguments for the discussion about the formation of the early Scythian cultural complex. The interpretative part of the article is preliminary and debatable in nature, but all the materials and facts set forth below are firmly documented.

-

- First results and their interpretations

- Magnetometry and Stone rings

The magnetometer survey was carried out using a Geometric 858 magnetometer in the so called duo-sensor configuration. The two caesium sensors were fixed parallel on a special light-weight carrying device. The distance between the two sensors on the device was 0.5 m, amounting to a line width of 1 m. The survey areas were measured in zig-zag mode, with an orientation measurement every five meters in order to locate the constant measurements relative to the line. The data was process in the software Magmap 2000 and the software Surfer for data enhancement and visualization. As with geoelectrics, the survey areas of the geomagnetic measurement were then located with a total station in order to integrate the visualized results into a geographical information system.

In total, an area of approximately 27.000 m2 was covered by the geomagnetic survey. The geomagnetic survey showed very good results under the conditions on site. Anthropogenically placed stones displayed a high contrast against the natural background. This is a very interesting effect since fired or otherwise processed materials (like e.g. bricks) are generally absent on site.

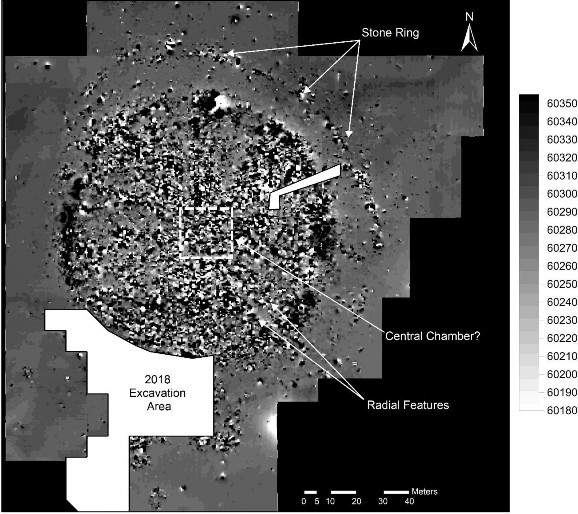

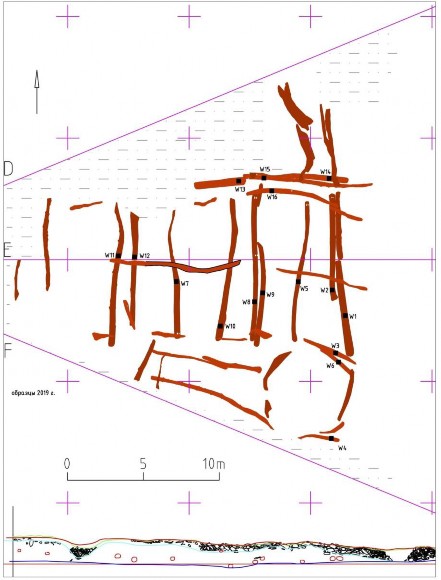

The composition of the stones will be analyzed in a future field campaign. Based on their reddish patina, they might have a high Fe content. The main result is a very clear stone ring around the monument which is not visible in the WorldView-2 data and neither in the high-resolution orthophotography, due to the high ground vegetation. The earth’s magnetic field had an average value of 60.290 nT at the time of the campaign. The data, processed with a lowpass filter and reduced by a coarse-grained moving average filter, show only minimal superposition by (interfering) bipolar anomalies compared to the raw data. This processing made it possible to sharpen the geomagnetic measurements in the area of potential chambers. Walking on site, some of the stone accumulations of the circle can be identified, but the extent remained unclear even when mapping out all visible stones with a total station. The outer ring of stones extends from the northwest to the southeast of the burial mound. In the northwest it is broken by the palaeochannel, likely eroded and carried away by the river. In the south we can see a number of other peripheral archaeological structures which might have made use of the stones from the central burial mound and the surrounding circle thus destroying parts of the site through sourcing building material. Despite difficulties due to surface roughness, we were able to cover the entire burial mound with the geomagnetic survey. It turns out that the radial features already seen in the satellite imagery are even more clearly visible in the geomagnetometry results. The burial mound seems to be separated into sectors running from the outside to the inside. Not all sectors have the same size. In the northwest the radial features are denser whereas in the north and west, the sectors show with great clarity. A very deep trench at the border of the burial mound is rendered in black. Its existence was already apparent from the excavation in 2018 but it might be the case that this circular ditch does not run through along the entire border of the burial mound. In the south internal structures of the burial mound are unclear and the image is very noisy. Simple filtering was applied, but without decent results. However, the centre of the burial mound seems to contain another structure. Rectangular in shape and roughly 18m x 19m it might be that the magnetometry survey was able to detect a large central burial chamber.

Fig. 1: Results of the geomagnetic survey (in nT) with the clearly visible outer stone ring of the burial mound, additional unknown peripheral structures in the south, clear internal radial division of the tomb and a potential central chamber.Additional peripheral archaeological structures were discovered south of the main burial mound. We were also able to define the extent of a large amorphous structure which was not completely excavated in 2018. We also surveyed the areas of the 2018 excavation where some stones had been left in place. The stones showed again with great clarity. The limited depth of the topsoil allowed for a similarly distinct imaging of the stones as if they would be lying out in the open.

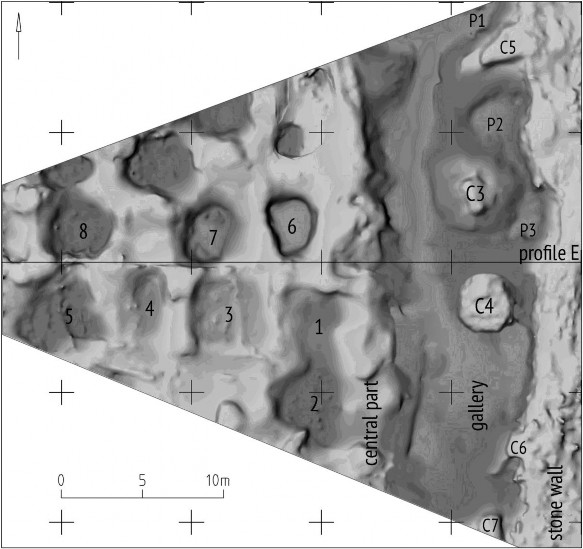

Fig. 3: Excavated stone rings and layouts east of the mound

The stone rings surrounding the central embankment are an indispensable element of the Early Scythian monument, and this element in the Early Scythian monuments quite unequivocally finds correspondence in the deerstone khirigsur culture of Mongolia. An interesting planographic detail is the paths (“rays”) going from the stone wall to the line of stone rings surrounding the mound. Stone structures of this kind are also fixed in some cases during the study of khirigsuur in Mongolia, for example, Ulaan Uushig I, Kh-1. The stone rings, as far as one can judge from the excavated part and by the magnetometric survey, are located in a row around the mound. On many culturally comparable monuments studied, the lines of the rings around the mound may be 2 or more. In Arzhan 1, for example, on the excavated site, 3 lines of rings are uniquely identified.

Among the studied rings, at least 3 types stand out (Fig. 4) according to the rocks of the stone, location and thoroughness of the structure.

Fig. 4: Types of stone ringsThe rings of the first type are constructed from large fragments of an underworked gray flagstone. This type of stone is quite rare among the stones of the wall or the main mound of the mound. In those cases when it does occur, we can assume that these are parts of the disassembled ring, since in most cases one of its edges has a rounded contour. The rings of the second type are made of limestone, but the color and texture of these plates are quite arbitrary. In addition, fragments of stones from the rings of the first type can be used in these rings, but the rounded side edge of these rings is not used as an external one. In one case (DE-R2 and DE-R3 rings), a stratigraphic correspondence is directly visible - under the ring of the second type, a layer of earth with small fragments of stone, characteristic of the rings of the first type, is traced. The rings of the third type are made of ragged rock. All of them are fixed on one of the sites, five in a row. The main conclusion that arises from these observations - the rings are not part of the architecture of the mound - they are traces of some ritual actions and could be destroyed at the end of the rite, and the stones of the rings could be reused. Moreover, the heterogeneity of the rings can also speak of the heterogeneity of the population using the mound as a cult place. Among the stones of the rings, only individual small animal bones were fixed, not far from them, but out of an unambiguous context - a bronze knife and adze, individual fragments of ceramics, without whole forms, which can be interpreted as early Scythian.

- DEM of the central part

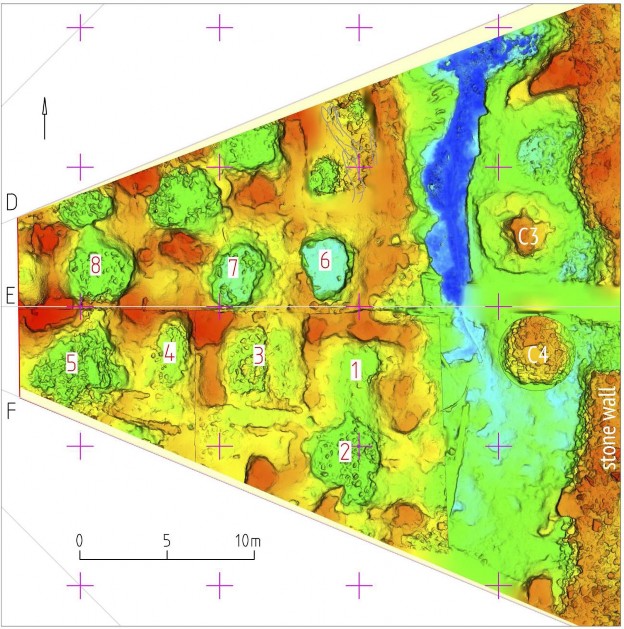

If the structure of the periphery of the monument can be quite clearly represented by the magnetometric plan, then the main part of the monument, completely covered with stone, on the magnetometric plan looks rather monolithic. We produced a digital elevation model of the mound during the preliminary exploration, and this method is more indicative in many aspects. In 2019, even before the start of excavation work, all the vegetation was removed from the mound, the grass was completely mowed and a new, more accurate DEM of the mound was built with a resolution of 3 cm / pixel, on which new important details were opened. Without vegetation, strict symmetry and a radial plan of the monument are manifested to an even greater degree on the surface of the monument.

Fig. 5: DEM of the central burial mound

- Stone wall and "gallery"

The central part is surrounded by a stone wall separated from it and a “gallery” located between them. The stone wall (up to a meter high and up to 12 m wide) is mainly composed of stone slabs with relatively regular dry masonry. The internal facade of the wall is defined quite clearly, while the external facade in many cases seems to have collapsed or destroyed.

Fig. 6. Profile of a stone wall (profile E)Two clay elevations (3-4 m in diameter) was built before or during the erection of masonry, are distinguished in the body of the wall on the investigated site. These clay “pillars” in the body of the wall are fixed on a 3D model made prior to the excavation (Fig. 5, C1, C2), and the same elevations can be seen in other parts of the wall. Perhaps the external facade of the wall was also decorated with clay, this requires additional confirmation (and additional profiles). Between the wall and the central part of the mound there is a “gallery”. On the modern surface, this is a lowering ring, covered for the most part with an ungrounded stone, after dismantling of which the main surface opens. No stone structures stand out here, all this stone is the result of a simple backfill plus traces of erosion from the wall and from the central part. The width of the gallery is 8-10 m, two clay elevations are allocated on the excavated area (fig. 7: C3, C4; fig. 5: C3, C4) spaced from the wall with a diameter of 4-5 m. There are three more clay elevations at the border of the wall and the gallery. At least three pits go from the gallery under a stone wall, they will be excavated in the next field season.

Fig. 7. DEM of the clay surface

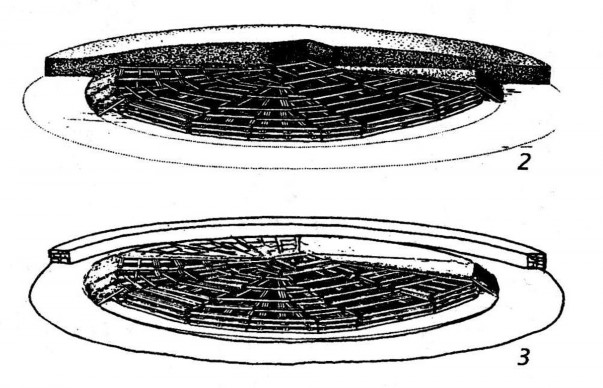

The first reconstructions of the initial appearance of Arzhan 1 mound suggested a continuous flat stone embankment over the entire monument. In the descriptions made before the destruction of the stone mound, some concavity of its upper surface is mentioned, but the presence of the wall and gallery is not clear. By the beginning of the excavations in 1971, the stone mound of the Arzhan mound ceased to exist. Only the central part of the monument (with a diameter of 75-80 m) was excavated, in the surrounding area only separate sections were examined and additional sections were made. A reconstruction was attempted based on these sections by Savinov in 2002 which resulted in a general view of the burial mound Arzhan 1. The same principle is also seen in the architecture of the Tunnug 1 mound, which indirectly confirms that the second reconstruction for Arzhan is more likely to be accurate.

Fig. 8. Reconstruction of Arzhan 1 according to M.P. Gryaznov (2) and D.G. Savinov (3)

Determining the principles of the design of sacred space is important for historical reconstructions. Separation of the central object by a distant wall is a traditional characteristic mainly of the Bronze Age; in monuments of the Scythian time it gradually disappears. On the territory of Tuva, this tradition is present in the so-called monuments of the Mongun-Taiga type and continues, possibly even in the early Scythian time. This tradition is close in many respects to the culture of Khirigsuurs of Mongolia, whose proximity to the Early Scythian culture is manifested in many aspects. - Stones on the central part of the mound

The central part of the mound is covered with a layer of stone. This layer does not seem to contain any additional architectural components. The stones covers the mound with a relatively even layer

When covering the mound, at least ten types of stone were used (a separate study will be devoted to this issue where we will identify the sources of these stones).

- Wooden structures

Fig. 9. Wooden structures at the heart of the central part of the mound. View from E.

At the heart of the central part of the Tunnug 1 mound lies a wooden grid. The logs were laid on top of one another without log cabin like cuts. Logs surrounding the mound were placed first. All radial logs coming from the center were placed after. Numerous holes were cut into the logs, apparently for transport purposes. The structure of their location (Fig. 10) certainly resembles the structure of Arzhan 1 mound, but nevertheless, the architectural differences are very significant.

Fig. 10. Plan of wooden structures and profile of the central part of the mound (profile E)

Currently, the arrangement of the logs accurately correlates with the clay structures located above it. Wood is not the main building material in Tunnug 1. It likely has an additional reinforcing function.

- Clay architecture

The main body of the mound consists of clay, and this is not a simple layer, but the remains of structures - walls and platforms. On the map DEM, all these elements are clearly visible, which continue both in the structure of the “gallery” and, in part, in the structure of the stone wall. Clay walls divide the mound into separate sections. Wooden structures play a supporting role. At the upper level, the “chambers” with clay walls were most likely covered with wooden ceilings, and only then hidden under a layer of stone. This reconstruction is not the only possible one and has not yet to be shown to be fully correct. In many depressions we find a log of very poor preservation under the layers of stone lying directly on the clay, but in most cases it is not possible to trace its direction. The most interesting in this regard are the western and southeastern parts of the embankment, where the chambers may not have collapsed yet. Clay walls divide the mound into separate sections, and the DEM generally reflects the structure of the clay level itself. On this basis, we can make a cautious assumption that in the outer ring of chambers might consist of roughly 32 individual sections, towards the center their sizes or number may decrease.

Fig. 11. Overlaying a clay DEM on a plan of wooden structuresAt the base of the clay walls lie one, two or even three logs. Clay for the walls was sourced somewhere nearby - in some cases the clay of the structure is almost indistinguishable from the soil in the periphery. The construction of one of the earliest Scythian mounds by a population familiar with the traditions of clay architecture is the most unexpected discovery of the past field season. The use of clay is completely unknown for the previous Mongun-Taiga tradition in Tuva as well as for the Deer Stone Khirigsuur Complex in Mongolia.

- Chambers" and pits

Several pits were recorded within the chambers of the mound; pits were excavated in chambers 1-4. The pits are precisely inscribed in the general wooden-clay planigraphy of the mound, and are definitely contemporary to the construction of the mound. The remaining pits will be examined in the next field season due to high water levels in the fall of 2019. In chamber 3, the stone filling of the pit was covered with a log. The pit’s depth was not more than half a meter (from the level of the wooden floor).

Fig. 12. A pit in chamber 3 before the excavation. View from the SThe investigated pits are not funerary; they did not contain archaeological material at all. At the same time, it is safe to say that the pits are clearly contemporary with the mound and do not bear the traces of a later invasion / robbery. Their significance is not yet fully understood; Materials for flotation were taken from the filling, the results of which may clarify the situation. The presence of pits is another fundamental difference between the Tunnug and the mound Arzhan 1, where all burials, treasures and sacrifices are made on the ground level. Here it can be noted that only a few percent of Arzhan 1's chambers contained archaeological material, the principle of its location is not fully understood, but it is not noted anywhere in the chambers of the outer ring.

- Early Scythian Finds

Fig. 13. Some finds. 1, 2, 5 - copper alloy, 3, 4 - ceramicsIn the central part of the mound, full funeral or ritual complexes have not yet been discovered, however, there are several finds made during the excavation of the clay layer which are unequivocally simultaneous to it. These are ancient bronze bits that were broken in antiquity without endings, a simple bronze plate, two fragments of ceramics completely uncharacteristic for Tuva, and, most interesting, a bronze buckle, which has a direct analogy both in Arzhan 1 mound and in individual monuments of the Scythian time. The metal of bronze ware is quite consistent with the metal of the Arzhan stage and is different from the metal composition of the subsequent Aldy-Bel culture.

№

item

Cu

As

Sn

Pb

Sb

Ag

Zn

Fe

Ni

Bi

fig. 13:1

bridle

main

4-5

<0,2

-

2-4

trace

-

<0,2

trace

~1

bridle

main

3-4

<0,3

-

2-4

trace

-

<0,2

trace

~1

fig. 13:2

main

<0,3

<0,5

<0,9

-

trace

<0,2

-

-

fig. 13:3

buckle

main

2-4

<0,2

-

3-5

trace

-

trace

trace

~1

Tab. 1: Metal composition of early Scythian items. - Magnetometry and Stone rings

-

Extremely generalizing, most supporters of the Central Asian theory of the origin of the Scythian culture see two main components of its composition - the culture of the khirigsuurs of Mongolia and the related Mongun-Taiga culture on the one hand and the culture of the post-Andronovo cultural circle on the other. There are a lot of versions and options, especially concerning the intermediate links from the Andronovo to the Scythians, but there are two main directions. Both of these elements are to some extent traced in the planigraphy, stratigraphy and the first finds of the Tunnug mound, in the materials of which, we hope, the initial materials for the Early Scythian complex will be found in an original form.

-

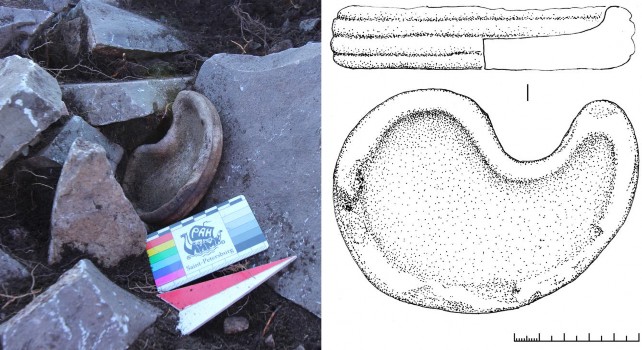

Additional finds and contributions

A wooden construction forms the base layer of the burial mound. This lattice made from complete larch trees was then covered in an irregular clay architecture, leaving gaps and depressions open. These compartments were later filled with stones and in some cases covered with wood (showing the undisturbed nature of the architecture). A petroglyph was found in the stone filling of one of the compartments. The filling of the pit was not disturbed, since also in this case, a preserved wooden log is leading over the stone filling which could be traced without any interruption. The petroglyph was lying upside down on the constructive clay layer. While turning the slab over, the depiction was recognised and photographed with the imprint in the clay still in situ. Its face-down position and broken state seem to indicate a secondary use. The petroglyph is between 2 mm and 4 mm deep and preserved to a length of 24 cm and a width of 16 cm. The larger half including a wheel and the axis has been preserved, but the second wheel is lacking since the stone was broken. The original width of the chariot depiction would have been around 30 cm. Despite scrutiny, the second half of the petroglyph could not be found in the filling of the pit. It is thus unclear if the chariot featured draught animals and a charioteer or not. To our knowledge, the case reported above is the first one in which a chariot petroglyph is directly stratigraphically associated with an archaeological complex encompassing wood architecture, and we can thus provide a terminus ante quem through wiggle matching. The creation of the petroglyph predates the construction of the burial mound since it was used in an undisturbed filling of a pit. This is a lucky case, considering Early Iron Age burial mounds are more often than not heavily impacted by looting. The wiggle matching of preserved constructive wood of the tomb yielded a date of 833–800 BCE (95% probability). This range constitutes a terminus ante quem for the creation of the petroglyph. The ‘chariot’ depiction, however, might be considerably older since its context within the Early Iron Age burial mound does suggest no conscious placement. Considering the slab’s broken state and inverted position, it might have been placed there by accident as a simple part of the filling of the pit.

Fig. 14: Chariot petroglyph with in situ clay imprint.

------------------------------------------------------------------

Tunnug 2020 Preparation Campaign Report

Key Points

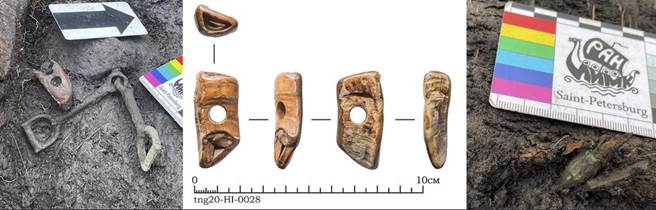

-Numerous finds from the earliest Scythians

-Preparation campaign despite no support from RGO

-First Scythian gold finds and horses

-Human sacrifice

-Independent Swiss funding allowed for continued research

Expedition Summary

2020 was a difficult year for field archaeology in general and archaeology in Russia in particular. Early on, the Russian Geographic Society refused to provide the logistics support due to Covid-19 (thus also cutting off access to transport, manpower, and further funding) and Tuva Republic was closed to foreigners and Russians from other administrative districts alike. Restrictions loosened in early June and it was possible to send a small Russian team into the field with a two week quarantine period. The authorities luckily allowed us to spend this period on site and we therefore did not lose too much time and money with unnecessary stays in hotels where the danger of getting infected would have likely been much higher.

With regards to financing, the funds provided by the Foundation for the Exploration of EurAsia were key to continuing the research and protecting parts of the site that were already uncovered in 2019 but not fully excavated. Although the team was small this time (20-25 people) and the late start of the campaign again made it difficult to reach the lower parts of the site, we conducted a very efficient preparation campaign for 2021. This year confirmed the importance of independently available funds for the project through the Swiss side that allows us to act even if funding inside Russia is cut off.

Figure 1: The excavation site in early fall.

We excavated primarily on the main burial mound. The main mound was documented based on the now clearly established architectural layers (published recently internationally peer-reviewed) - stone, clay and wooden structures. The clay architecture is beginning to change views on the origins of the Scythians already, pointing towards a possible Central Asian origin. We were unable to explore the deep pits due to flooding on site. These structures are conserved and will be excavated next spring. An additional burial, animal bones, the fragments of a cauldron vessel, as well as some smaller finds among the stones were documented. Under a layer of stone on the surface of the clay architecture, numerous horse bones with elements of horse bridles were recorded (an important element of Scythian material culture and the earliest ones of its kind).

All bones were fragmented, but appear to be in relative anatomical order. These likely were horse sacrifices performed on the surface of the mound before it was covered with stones. Final conclusions can be drawn after a long reconstruction process - processing of more than thirty 3D models and work with a palaeozoologist. We also found a significant number of human bones on the clay surface. The data is still being processed, but a preliminary interpretation would go into the direction of human sacrifice and not proper burial. Despite the small campaign, this was the field season with the most Scythian finds so far. As we are excavating larger and larger parts of the main burial

mound we are stumbling upon some of the earliest horse gear for riding and a first piece of Scythian gold (Fig. 2-3).

Figure 2: Horse bones and bronze horse gears (some of the earliest known Scythian bridles).

Figure 3: Earliest Scythian gold – probably part of a decoration of riding equipment.

The season resulted in the completion of the south, southeast, and east periphery, as well as the excavation of two sectors of the main mound down to the level of the chambers, and the discovery of a complex assemblage of sacrifices in a rather unexpected place. These are the first archaeological finds that are showing the Early Iron Age

significance of this monument.

Figure 4: Areas excavated in 2020

The reduced fieldwork gave me time to write up a lot of research and we managed to publish four international peer-reviewed papers with another paper and a book about the periphery in preparation. The Foundation for the Exploration of EurAsia appears in the acknowledgements of every paper:

-

Sadykov, T., Caspari, G., & Blochin, J. (2020). Kurgan Tunnug 1—New Data on the Earliest Horizon of Scythian Material Culture. Journal of Field

Archaeology, 1-15.

-

Caspari, G., Sadykov, T., Blochin, J., Bolliger, M., & Szidat, S. (2020). New evidence for a bronze age date of chariot depictions in the Eurasian Steppe. Rock Art Research, 37(1), 53-58.

-

Milella, M., Caspari, G. R., Kapinus, Y., Blochin, J., Sadykov, T., & Lösch,

S. (2020). Troubles in Tuva: demographic patterns of interpersonal violence in a Late Antique nomadic community from Southern Siberia (2nd-4th c. AD).

-

Caspari, G., Blochin, J., Sadykov, T., & Balz, T. (2020). Deciphering Circular Anthropogenic Anomalies in PALSAR Data—Using L-Band SAR for Analyzing Archaeological Features on the Steppe. Remote Sensing, 12(7), 1076.

The project got international press coverage including on SRF, ScienceDaily, IFLScience, Ancient Origins, and a longer article in National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/09/ancient-empire-collapse-violent- nomad-burials/

New insights into the emergence of the Scythians

The Tunnug 1 site is much more complex than a simple soil or stone mound mound over a burial as is often the case with smaller Early Iron Age sites. The archaeological complex consists of several architectural features dating to the Early Iron Age and a plethora of structures belonging to later time periods. We structurally distinguish the central part of the main mound built from wood, clay and stone; the surrounding gallery with clay structures and pits; a wall surrounding the gallery, constructed from stone slabs; stone rings and layouts surrounding the complex as a whole; a large amorphous mound and several smaller contemporary funerary and ritual structures dating back to the first centuries A.D., partially destroying stone rings and the edge of the stone wall in the southern periphery of the site; medieval burial objects in the southern periphery; and finally, stray finds dating to the Middle Bronze Age.

Around 20% of the Early Iron Age component of the site have been excavated, including parts of the main mound, gallery, wall, as well as stone structures and rings in the immediate periphery. The prepared sectors and excavated quadrants are marked below in red. Note that due to the late start of the campaign due to Covid-19 we were unable to excavate the deeper layers this year. This will happen in May 2021.

Stone rings surrounding a central mound are a frequent element of Early Iron Age kurgan sites in Central Asia, and this architectural characteristic finds clear parallels in the deer stones and khirigsuurs complex of Mongolia. A long-standing question is whether they reflect ritual practices contemporary with the construction of the burial or a gradual build- up reflective of a longer period where the burial mound served as a place of post-funerary ritual practices. Before the start of the 2019 excavations, a geophysical survey of the periphery of the site was conducted. Due to the characteristics of soil formation in the area of the site and the vegetation, the peripheral structures surrounding the main kurgan are mostly invisible on the surface. Out of the three applied geophysical prospection methods (ground-penetrating radar, geoelectric resistivity, geomagnetometry) only the geomagnetometry yielded good results. The peripheral structures appeared very clearly in the geomagnetic data. The eastern periphery of the main burial mound showed these features to be largely undisturbed by later anthropogenic activity and was therefore

chosen for excavation. The stone rings, as far as can be judged from the excavated part and from the geomagnetic survey, are arranged around the mound in a single row. The number of rows is variable for different sites. A row of stone circles can surround only part of an Early Iron Age mound. At Arzhan 1, for example, from 1 to 3 lines of rings are identified. At Arzhan 2 an unorderly circular arrangement was chosen with up to 4 short rows of stone circles closely aligned.

Among the studied rings at Tunnug 1, at least 3 types can be distinguished based on the type of stone, the location, and constructive tidiness. The rings of the first type are constructed from large fragments of worked gray flagstone. This type of stone is quite rare among the stones of the wall and the main structure. In cases where it does occur, they are always found on top of the stone surface of the main mound. We can hypothesize that these stones pertain to disassembled rings. In addition to being of the same type, they also display the same artificially rounded contours on one side. The rings of the third type are made of an unorderly assemblage of unworked rock of reddish color. We continued to excavate ritual stone rings around the main monument.

To cover the mound and to build the rings, at least ten types of stone were used (a separate study based on sourcing analyses will be devoted to this issue). On the mound no obvious system concerning their distribution has so far been noted. Within sight of the

kurgan, only one possible quarry was identified, but the type of stone found there is not the most common on the site. We don’t know much about the types of stone in Arzhan 1 and therefore lack a mean for comparison. Arzhan 2, however, was built almost exclusively with Devonian sandstone and its quarry was found in 2 km distance from the site. The situation on Tunnug 1 is completely different.

The main conclusion that results from these observations is that the rings are not all contemporary with the initial construction phase of the royal kurgan. They are in part remains of later ritual actions. The stones from the rings could be reused or destroyed with the next ritual. At the same time, the diversity of the rings may also hint towards the heterogeneity of communities that used the kurgan as a place of worship. Different sources of stones, different construction technique (shaped slabs in the rings of the first type, simple piled stones in the rings of the third type), different planigraphic positions of the rings of different types could be interpreted as reflecting chronological and cultural differences.

Among the stones of the rings, only individual small animal bones were documented. Not far from them, but without an unambiguous context, a bronze knife, a socketed axe, and some fragments of ceramics were found which can be interpreted as Early Iron Age based on their typology. An interesting planigraphic detail are the broad stone pavements connecting the stone wall with the line of stone rings surrounding the mound. Similar stone structures have been documented in some cases in the khirigsuurs of Mongolia, for example Ulaan Uushig I, Kh-1 or Tubshin Nuur, Kh-3. Another distant, but nonetheless interesting parallel in this case are the so-called “kurgans with mustaches” [kurgan s usami] from Kazakhstan and the southern Ural. The dating of these appendices is still debatable, and they might not belong to the original construction phase of the burial mounds. These architectural features are consistently located in the east of the burial mounds. Based on the geomagnetic data, we do not expect finding additional appendices. At Tunnug 1 they seem to only appear in the east.

Presupposed destructions by Soviet machinery

In the 1970s Gryaznov had pointed out that stone was sourced at the Tunnug 1 mound

for the construction of a nearby winter road during Soviet times. This was a major concern before the start of the excavation because heavy machinery might have destroyed a part of the site. The geomagnetic data showed the structure of the periphery quite clearly, but the central part of the site, being completely covered with stone, is characterized by a large amount of noise. Already during the survey campaign in 2017, we produced a digital elevation model (DEM) of the kurgan and this method proved to be in many ways more effective in revealing the structure of the main burial mound. In 2019 before the start of the excavations, all vegetation was removed from the mound, the grass was completely mowed down and a new, more accurate DEM of the mound with a resolution of up to 3cm/pixel was generated through photogrammetry. This revealed the architectural outline of the mound in a new level detail.

With the vegetation removed, the wheel-like structure of the site with radial spokes coming from the center and going to the periphery is even more evident. Some small areas, which we can interpret as traces of destruction, are visible. However, it seems that if stone was sourced at all, this has only led to minor signs of destruction. Generally, stones would have been taken from the gallery surrounding the central mound, where stones are free of vegetation and easily accessible. But also in this case, we can only see slight alterations of the original form of the mound. We investigated the remains of a defunct winter road nearby which showed no stones that would immediately suggest the kurgan as the source. In summer the area is frequently flooded and impassable. In winter, the ground is deeply frozen and does not necessarily require a road for passage. It might be that Gryaznov interpreted the open parts of the gallery which remain free from vegetation due to all water being drained quickly into the ground, as destructions caused by sourcing stones for a road. From the aerial photographs and the DEM, these depressions are clearly a structural part of the site, but this was hard to grasp from the ground in the 1970s.

In addition to evaluating the general structure and preservation conditions of the mound in the DEM, it is possible to note individual areas that deserve attention. The western and southeastern sectors of the central mound have almost no depressions on the modern surface. Perhaps this means that the underlying construction in these areas has not collapsed. Here it will be necessary to conduct a particularly detailed excavation of the upper levels to try and document the wooden structures located above the clay layer. The westernmost part of the gallery sees an interruption of the depression, bridging the wall with the central part of the mound. Perhaps an additional architectural element can be documented here in future campaigns.

Stone wall and gallery

The central part of the kurgan Tunnug 1 is surrounded by a stone wall framing a gallery in between. The stone wall - up to a meter high and up to 12 m wide – is mostly composed of stone slabs piled up in relatively regular dry masonry. The internal facade of the wall is clearly defined, while the external facade on the studied area seems to have collapsed. Two clay hillocks with 3-4 m in diameter were built before or during the construction of

the masonry. Similar elevated areas can be seen in other parts of the wall. It is possible that the external facade of the wall was also formed with clay, but this requires additional confirmation.

The wall and the central part of the mound are separated by a gallery. On the modern surface it looks like a ditch, covered mostly with stones and lacking vegetation. This layer of stones lies on top of the geological layer. No stone structures can be identified inside the gallery. All stones inside the gallery are the result of a simple filling process. In part, erosion might have had an additional impact on smoothing out the borders of the main mound and the wall with stones gradually sliding into the gallery. The width of the gallery is 8-10 m. At least three pits in the gallery seem to be partially covered by the stone wall. Clay and wood structures generally lie lower than stones. The entire structure of the monument looks unified and planned, despite the different construction techniques that

were used in its make-up. The DEM clearly shows that additional clay humps and pits

will be found in the gallery and in the stone wall.

A find made in association with the wall in 2019 serves as a terminus ante quem and indirectly confirms the Early Iron Age date of this part of the architecture. This tear- shaped stone vessel has widespread analogies. It is well-known in the Aral Sea area from the sites of Uigarak and Southern Tagisken, examples have been found in northern Kazakhstan and Arzhan 2 in Tuva. Stone vessels of this type are in most cases found in kurgans dating back to the 7th century B.C. Here we can present a likely earlier example that is also associated with the Early Iron Age and supports that the wall is part of the main burial mound construction. The stratigraphic relationship of the stone vessel with the wall, however, leaves room for interpretation and does not necessarily have to be completely contemporary with the underlying stone construction.

Previously unknown clay architecture in Siberia

In the Late Bronze Age Mongun Taiga architectural tradition, all kurgans are exclusively built from stone. Similarly, khirigsuur monuments also see the almost exclusive usage of stones as a construction material. One of the few exceptions is the Huahaizi (Sandaohaizi) site in northern Xinjiang which contained remains of wooden logs and “earthen heaps”. The vast majority of Early Iron Age burial mounds in Tuva are constructions made from stone. Exceptions are very rare. During the Aldy-Bel stage, most of the known mounds

were built from stone. The kurgans Arzhan 1 and Arzhan 5 are essentially wooden structures covered with stone. No other materials are mentioned by the respective excavators. Before starting the excavations on the Tunnug kurgan, we therefore expected to find wooden structures at the base level, but assumed that the main body of the mound consisted exclusively of stone.

After excavating two sectors, it became clear that the central part of the Tunnug burial mound is made up of clay and covered with a relatively thin layer of stone. This stone layer does not appear to contain any additional architectural components. Before the start of the excavation, we mapped all vertically placed stones visible on the surface of the mound. It seemed important to identify all possible indications of consciously arranged stone structures. With the progression of the excavation, however, it became clear that these vertical stones on the surface are connected with the edges of depressions (“chambers”) rather than being originally placed with a specific intent.

The main body of the kurgan consists of clay. The clay is not a simple constructive layer, but was rather shaped to form architectural elements like walls, ramparts, humps, pillars and platforms. On the DEM of the clay level all these elements are clearly visible. They continue further into the structure of the gallery and, to some extent, in the structure of the stone wall. Clay walls divide the mound into separate sections with individual compartments.

A radial structure of larch logs as the base layer of the Tunnug 1 burial mound seemingly only played an auxiliary role. The wood was covered in clay forming compartments with clay walls. These compartments were most likely closed with a wooden ceiling made up from additional wood beams, and finally covered with layers of stones. This is merely a tentative, although likely, reconstruction which has yet to be further supported. Often poorly preserved wood is found under the layers of stone lying directly on the clay. In most cases it is not possible to trace its direction or estimate its quantity due to the bad preservation. The most attention in this regard deserve the western and southeastern parts of the mound, where the compartments may not have collapsed yet.

Clay walls divide the mound into separate sections, and the DEM of the kurgan before excavation generally reflects the structure of the clay level. On this basis, we can make a cautious assumption that there may be about 4-5 rows of compartments between the outer border of the main mound and the center of the mound. We estimate around 32 chambers in the outermost ring with their size and number decreasing towards the center. Based on this, the total number of compartments in the central part of the kurgan will be about one hundred.

At the base of the clay walls lie one, two or even three wooden logs. Clay for the walls was sourced somewhere close to the kurgan - in some cases, the clay of the structure is almost indistinguishable from the geological layer. The usage of clay as a construction material is completely unknown in the previous Mongun Taiga tradition in Tuva and does not find parallels in the deer stone khirigsuur complex. Clay sometimes is used on sites with Scythian material culture, but they all postdate Tunnug 1. In the few cases where clay is used, it never serves as the main construction material. Finding one of the earliest burial mounds of Scythian material culture using clay as a construction material is

unexpected. It raises the question whether the origins of Scythian material culture contain

a component beyond the regional Late Bronze Age precursors. Could there be an influence by a community familiar with the traditions of clay architecture?

The wood structure

The radial wooden structure with internal “chambers” in Arzhan 1 is often referred in the scientific literature as unique. The excavations during summer 2019 and 2020 at the site of Tunnug 1 clearly revealed a comparable structure of larch logs underneath the burial mound. We can report that there is at least one more “royal” kurgan with the same architectural tradition. This will have implications for our perception of the Arzhan horizon in the Uyuk Valley and possibly lead to a clearer idea of the time span associated with these constructions.

The base layer of the central mound of the Tunnug 1 site is formed by a wheel-like wooden structure with spokes coming from the center, separated by crossbeams. Larch logs were used for this construction after their bark was likely removed. The logs were