FIELD REPORT

ON THE

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS

AT ILIBALYK SITE

(MEDIEVAL CHRISTIAN NECROPOLIS),

KAZAKHSTAN IN 2023

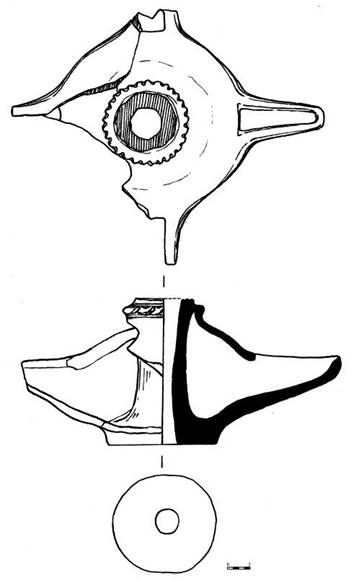

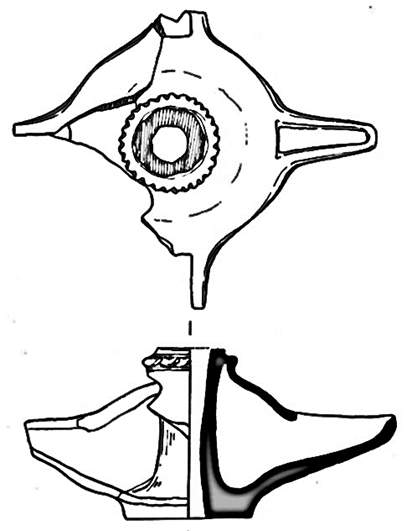

FOUR-NOZZLE LAMP (CHIRAG)

Almaty 2024

LIST OF EXCAVATORS

Introduction

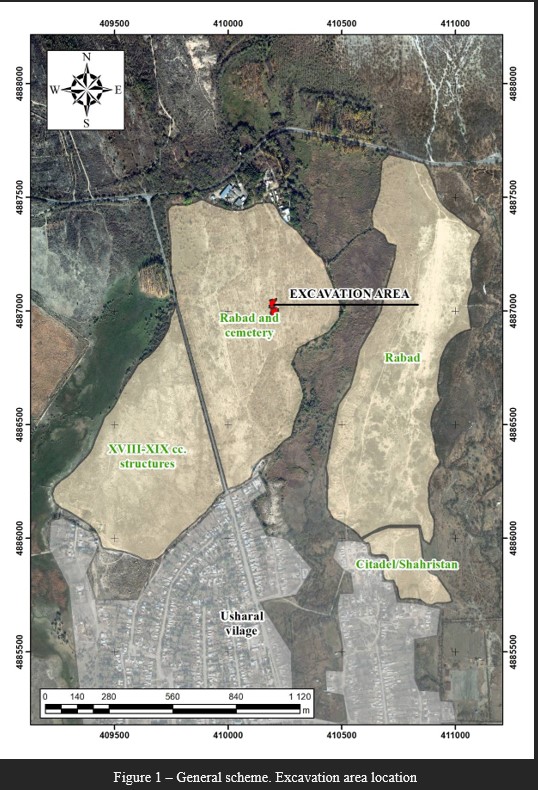

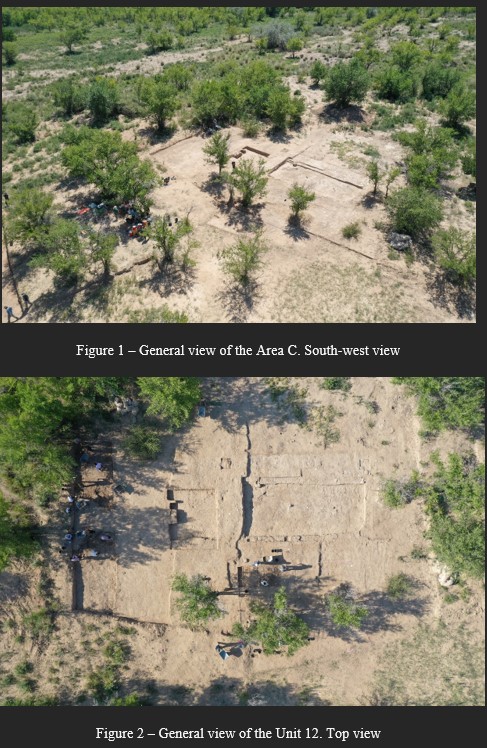

Excavations at Usharal-Ilibalyk in the Republic of Kazakhstan has now completed their eight season. This past summer, July 9-30, 2023, the international excavation team continued archaeological investigations within Area C of Field IV, a Christian cemetery and funerary chapel at the Ilibalyk site, a 5000 m 2 medieval city that existed between the 10th through 15th centuries.

This project is under the direction of Dr. Dmitry Voyakin (Archaeological Expertise, LLC and International Institute for Central Asian Studies); with field direction under Mikhail Gurulev (Archaeological Expertise); and financial sponsorship by the Society for the Exploration of Eurasia (Dr. Christoph Baumer, President) in joint-participation by Lipscomb University’s Lanier Institute for Archaeology (Nashville, TN, USA, Dr. Stephen Ortiz, Dr. Thomas Davis). Additional sponsorship has also come from an anonymous group of private donors both in the United States and the Republic of Korea. In addition, both professional archaeologists, archaeology students, and local and international volunteers from 12 different countries have participated in this project over the years exceeding 200 participants and laborers. Of special note is the team of workers from the village of Usharal (Panfilov district) itself, who have provided excellent labor consistently every year together with the support of the local administration (with special thanks to the village akim (mayor), Tanatar Zhangaziev) and townspeople who annually extend their hospitality.

This excavation’s methodology, processes, and results have been carefully documented at the conclusion of each season. In addition, as the bibliography indicates, several recent publications have provided a clear record of both the results and interpretations rendered based on both the archaeological and historical context. The annual field reports can be found at https://www.exploration-eurasia.com/inhalt_english/frameset_projekt_aC.html.

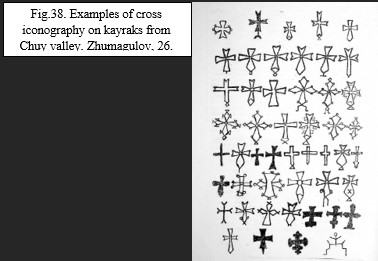

The Ilibalyk investigations have provided groundbreaking information concerning the presence of medieval Christianity, specifically Church of the East (Nestorian), as it existed between the 12th-14th centuries in the Zhetisu (Semirechye) region on the territory of today’s Kazakhstan. The Christians at Ilibalyk were part of a larger Christian community throughout Zhetisu that extended the length of the so-called Silk Road of Central Asia during the Mongol period, and most specifically under the domain of the Chagatay khanate between the mid-13th through early 14th centuries. To date, 110 graves have been excavated in the Christian cemetery (estimated 60 x 70 m) located in the northern section of the medieval city. In addition, with the discovery of a funerary chapel in 2020, this structure was studied more thoroughly this season with the most recent discovery of either a northern martyrium wing to the chapel or a stand-along mausoleum which contains at least one grave. This tomb contains a person who is potentially a founder of the Christian community and whose burial indicates he was highly revered by the Christian inhabitants of Ililbalyk, with possibly two more graves identified within this structure.

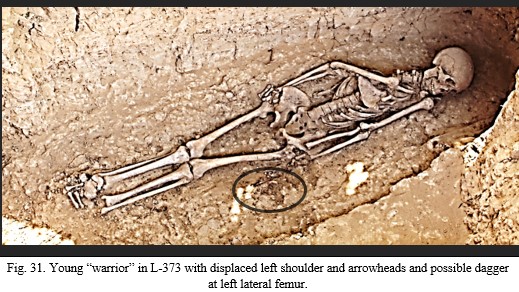

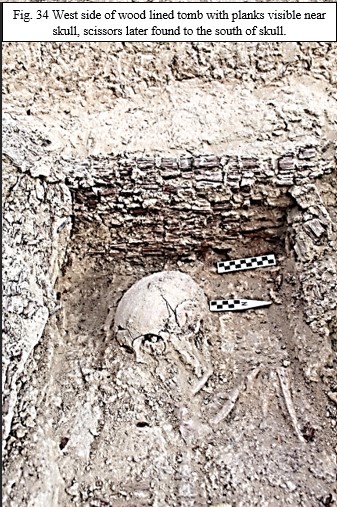

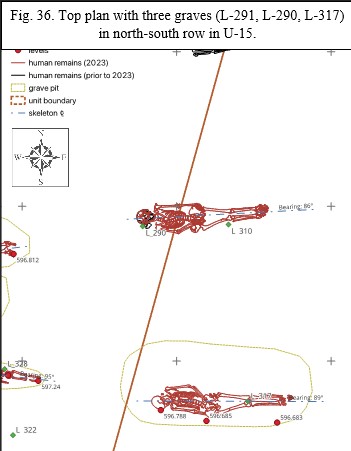

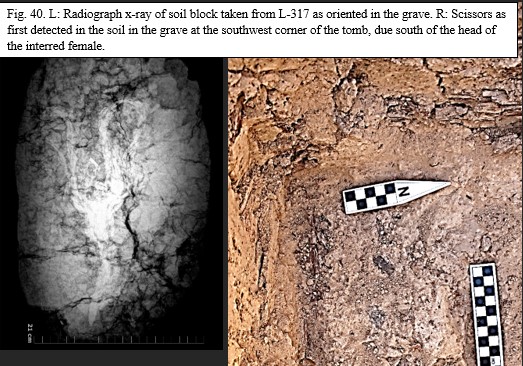

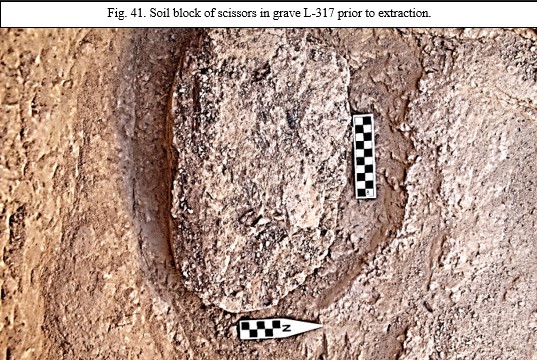

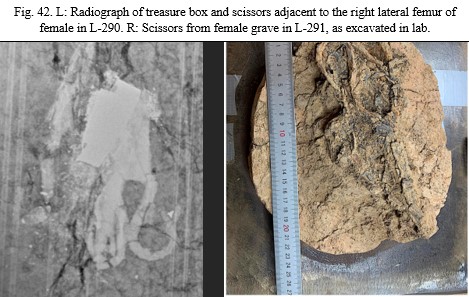

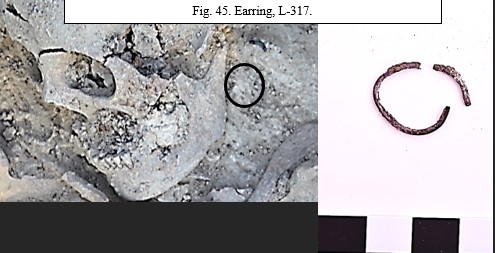

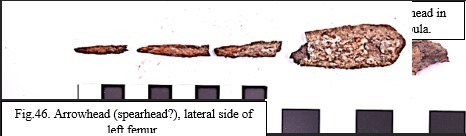

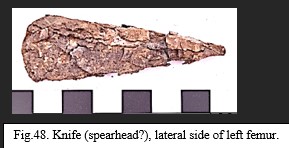

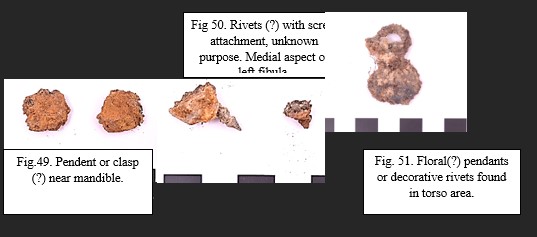

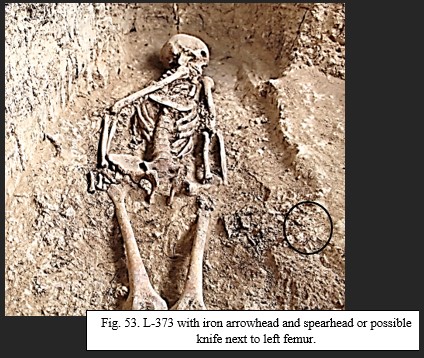

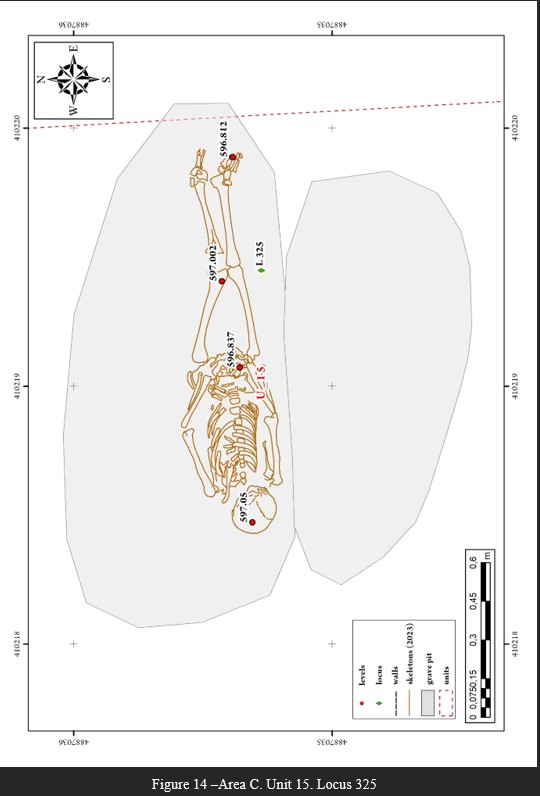

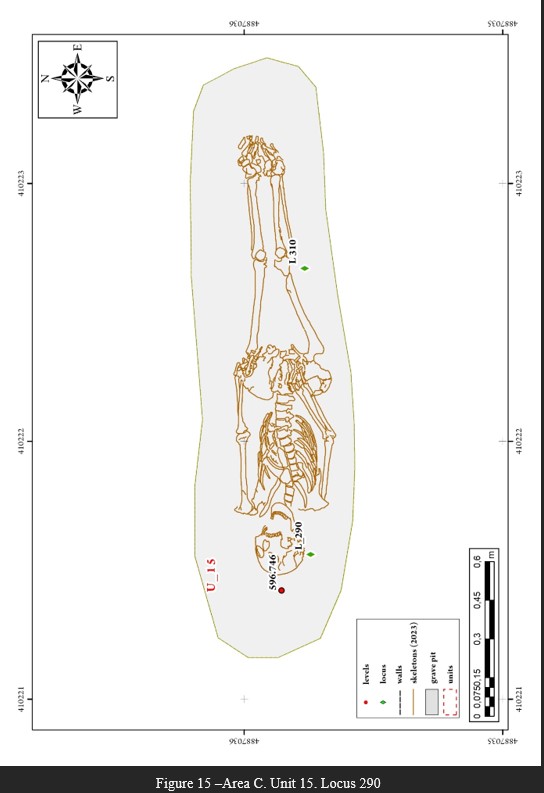

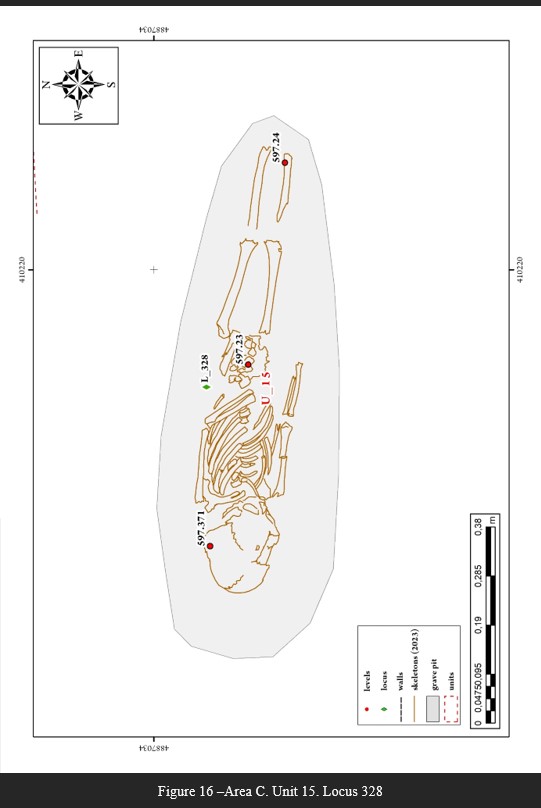

As the following report will explain, more clarity has also been provided regarding a section of the cemetery that is best interpreted as containing burials with Turko-Mongolian nomads based on the interment methods, specifically grave goods. This is the same section of the previously discovered high-status female (L-290) buried with a boqtag headdress (an elite status symbol) whose remains were subsequently examined in a controlled laboratory setting. Her burial not only included the boqtag, but other items placed around the body, such as a dagger, a small jewelry box, and scissors. This season’s excavations revealed another female in an elaborately constructed wooden enclosure who also had a pair of scissors placed to the right (south) of her head; as well as a young “warrior” who was discovered with evidence of weapons placed in this tomb at the time of burial. Thus, these findings may be the first archaeological evidence for nomadic Christians who were known to exist in the region between the 11th-14th centuries.

Such findings, as detailed below, clearly demonstrate a complex community of Christians, with an organized clergy, burial rituals based on the Christian rite, structures dedicated to the declaration of the Christian faith during those funerary rites, and accompanying markers of those graves to perpetuate the memories of the dead. This season’s excavations also extended the border of the cemetery to the east, which is leading to the team’s ability to discern the exact boundaries of the cemetery. The combination of both osteological and cultural material investigations continues to yield a growing abundance of specific information that will aid scholars, historians and archaeologists in the study of Central Asian Christianity and late medieval culture far into the future.

Research Questions and Objectives

The excavation team entered the 2023 season with the following questions:

What is the relationship and function of the section between funerary chapel and the cemetery?

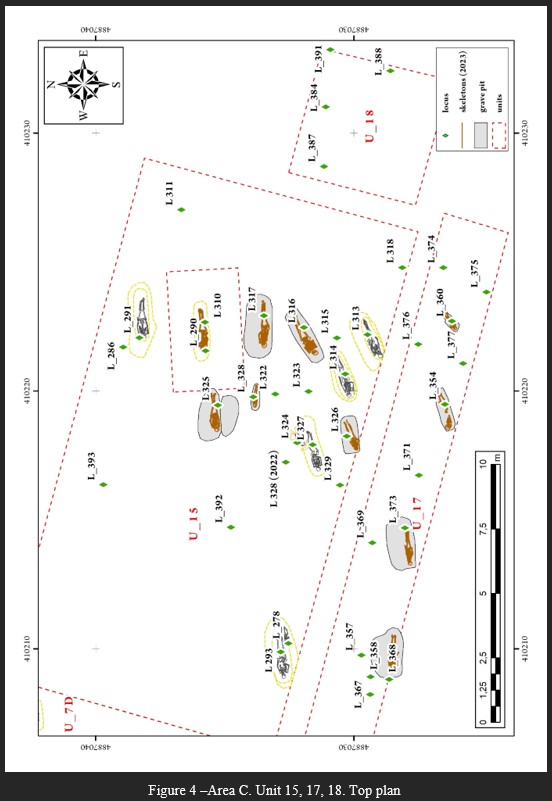

Do graves continue to the east and south of Unit 15, the easternmost unit of the cemetery in Area C, and is this section of the cemetery indicate a distinct sub-culture within the cemetery in comparison to other graves investigated so far?

Are more graves present in Area B (east of Area C and D) which can further help the teams understanding of the cemetery’s boundaries?

Based on the discovery of water mill stones in 2022 on the stream to the east (Karasu), can more be discerned there with the use of LiDAR drone technology?

Can LiDAR scanning help yield more information concerning the overall Ilibalyk site?

Based on these research questions, an excavation plan was adopted as follows:

Further excavations on the previously revealed graves of excavation Unit 15 will be conducted with special focus on those graves that could not be examined because of the block extraction of L-290 conducted in 2022.

Excavation units will be dug to the east and south of Unit 15 to determine if graves continue in those directions.

Excavations north and east of the funerary chapel will be conducted to determine if any other structures or graves are present in those locations. There will also be an attempt to discern the medieval occupational surface in and around the chapel.

Due to the purchase of a new LiDAR drone, scans will be conducted across the entirety of the Ilibalyk site to provide an updated geodesic survey as well as potentially locate possible structures or features that may require further investigation via excavation.

Excavation Methodology and Equipment Utilized

Because previous methodology and equipment has been detailed in previous reports, the reader is encouraged to consult those reports which provide descriptions and specification on the use of a theodolite total station for GIS, photogrammetry, and basic elevation. Excavation techniques involved the use of earth moving equipment for the removal of initial non-diagnostic agricultural topsoil, shovels, and hand tools such as trowels and even dental tools for more delicate work within graves. The osteological field procedures are discussed in the Field Forensic section. All the soil from graves was 100% sifted to insure the discovery and retrieval of all cultural material.

All activities were photographed and described using written documentation. The following report provides unit and loci descriptions explaining the excavation processes, findings, and interpretations. Excavation baulk profiles were drawn and described. Identified features were provided loci numbers and elevations taken for these features and/or for any special cultural finds. All pottery and other cultural material was carefully cleaned according to procedure with key examples drawn and described below. All the finds were recorded into the overall database, which will soon be made public via an online application.

Special care and documentation were provided to the human remains according to set procedures of previous digs. The remains were packed to carefully preserve the remains which are later examined in laboratory conditions. While field observations of the remains are taken, final conclusions regarding age, sex determination, and possible pathology are made in that setting can are official documented in the lab and will be provided in a future and final report.

Because the LiDAR scanning drone was utilized for the first time, a more detailed report concerning its usage and initial findings are provided below.

LiDAR Survey Report

Introduction

The 2023 expedition utilized a drone-mounted LiDAR solution to generate a dense three-dimensional (3D) point cloud model representing approximately 4 sq km of the immediate excavation site and surrounding context. The point cloud was then analyzed to gain further understanding of ground surface characteristics at and around the excavation site and to assist decisions regarding potential new dig locations. It was hypothesized that analysis of a high-resolution digital reconstruction of the ground plane might exhibit anomalies in the ground surface that could be indications of human-made structures or artifacts beneath. The LiDAR scans were also used to confirm and supplement measurements taken on the ground of various excavation features.

General Description

LiDAR is an acronym that stands for Light Detection and Ranging. The technology has been around for several decades, but in recent years has seen new applications developed in coincidence with the growth of the remotely controlled aerial drone industry. These applications range from surveying and mapping to environmental management and agriculture.

A LiDAR unit utilizes a reflected laser pulse to measure the distance to some observed subject. If the location of the LiDAR unit is known, as well as the direction of the laser pulse, it is then possible to determine the location of the observed subject in space in some coordinate system. When LiDAR units are part of a complete hardware and software solution, they can be used to generate informationally dense virtual reconstructions of 3D subjects, be it a small vase or a mountain range. The resultant data sets are called point clouds.

A point cloud consists of data points in a cartesian coordinate system representing three-dimensional geometry. Each point in the cloud corresponds to a specific location in space and is defined by its X, Y, and Z coordinates, sometimes accompanied by additional attributes such as color, reflectance, return count or intensity information. Software may be used to generate 3D models from the point cloud data for visualization and analysis.

In previous years, the excavation team utilized photogrammetry from drone flight imagery to produce 2D and 3D virtual reconstructions of the Ilibalyk site and context. While photogrammetry and LiDAR share some capabilities, it is important to understand the differences between the technologies particularly as it applies to our use case.

For our purposes at Ilibalyk, photogrammetry provides a medium resolution reconstruction of surface shapes that has value when understanding site conditions at a larger scale. Photogrammetry employs computers running specialized software to construct a representative digital model of a subject (typically three-dimensional) by analyzing dozens to thousands of images taken at different angles and reference points. It is computationally intensive, and the usefulness of the end product depends on the software/hardware used, the quality and quantity of input images, and the physical and form characteristics of the subject. It is a recognized weakness of photogrammetry that subjects with dense overlapping features such as vegetation produce models with confusing or inaccurate reconstructions.

The Ilibalyk site has large areas covered in dense shrubbery and trees. LiDAR offers the possibility to gain some understanding of the ground topography under these areas which has not been possible with photogrammetry. LiDAR’s advantage in such areas is due to the ability for the laser pulses to either penetrate leaves or pass between them. Where photogrammetry offers a calculated guess of a surface shape based on multiple photos, with LiDAR each reflection of a light pulse may be generally accepted as a true location of a physical surface at the given location in space, be it a leaf or a ground plane. Therefore, point clouds generated by LiDAR scans provide a high degree of information of areas covered by trees and vegetation compared to photogrammetry generated models of the same.

Specifications

The LiDAR solution utilized on this project was the DJI Zenmuse L1 LiDAR unit payload mounted to the DJI Matrice 300 RTK enterprise drone platform. The Zenmuse L1 includes an RGB camera for mapping color to the resulting point cloud. The GNSS (GPS) receiver and real-time kinematic (RTK) capabilities of the drone platform provide the precise location information (up to 2 cm horizontal precision) required for accurate LiDAR modeling, while the Zenmuse L1 employs a high accuracy inertial measurement unit (IMU) capable of sensing the laser pulse direction to within 0.025°(roll/pitch) and 0.15°(yaw). To locate a point within some reference spatial system, three things must be known: location of observer, angular direction from observer to subject, and the distance from observer to subject. For a LiDAR system, the reference location is provided by the GNSS receiver, direction (angle) to subject by the IMU, and distance to subject measured by the laser pulse. This DJI LiDAR solution, in a typical use-case with recommended settings, can generate model data at a rate of 240,000 – 480,000 points per second of flight/capture time.

The specifications and settings for each individual flight mission at Ilibalyk varied slightly based on various factors at the time and as the process was adjusted to yield higher value data. Generally, the scan missions used the following parameters:

- Drone flight speed: 5.5 m/s (12.3 mph)

- Scan altitude (above ground plane at starting position): 60 m (196 ft)

- Flight Pattern: The DJI drone flight planning software creates an optimized flight pattern for optimal efficiency and coverage based on the desired scan area. The pattern generally consists of back-and-forth passes across the subject area ensuring complete and consistent data capture. In our case, adjacent passes on the flight pattern were approximately 35m apart (115 ft).

- RTK or PPK: Both real-time kinematic (RTK) and post-processed kinematic (PPK) workflow was utilized. Due to connectivity challenges in the field, most missions had to be processed using a PPK workflow based on GNSS correction data provided by a base station in nearby Zharkent. For GNSS based locationing to be usable for LiDAR scanning purposes, the locations as calculated based on GNSS satellite signals must be corrected and made more precise to account for factors such as atmospheric conditions. (Note: GNSS refers to the Global Navigation Satellite System, a system that incorporates satellite systems developed by different countries, including among others GPS (United States), and GLONASS (Russia). The GNSS satellite system used in Kazakhstan and therefore for purposes of LiDAR on this project is the Russian-developed GLONASS.)

- LiDAR frequency/pulse: 240Khz. Therefore, our flight missions captured data at a rate of nearly a quarter-million cartesian points per second of flight time.

- Return count: Double. This setting tells the LiDAR unit how many reflections to register for each individual laser pulse. For example, when using dual return, the sensor may recognize a laser return (reflection) off a leaf at the top of a tree, and then a second return off the ground beneath, effectively providing double the model clarity per laser pulse in contexts with vegetation.

- Scan Path Overlap: 50%. This setting determines the flight path plan such that the scan surface of each pass of the drone overhead will overlap with the adjacent scan surface pass by the specified percent.

- Cloud Density (points per unit of area): 447 points/sq m (42 points/sq ft). This is the calculated assumed density based on the flight plan. Actual cloud density on some of our scans is much higher, sometimes by a factor of three.

- Ground Sample Distance: 1.36 cm/pixel for nadir aerial photography. (A function of altitude, camera resolution, and lens parameters, GSD describes the real-world distance represented by a single pixel in an overhead image.)

- Scanning Pattern: Repetitive. The Zenmuse L1 unit has two modes defining the pattern the laser takes as it sweeps across its view. The Repetitive pattern is a simple back-and-forth motion optimal for scanning large areas such as our context. The other available mode is Non-Repetitive, which is a spiraling laser sweep more suited to scans of complex-shaped individual objects.

- Coordinate Reference System (CRS): The models produced in initial processing from the captured LiDAR data were assigned the projected coordinate reference system WGS 1984 / UTM 44N

LiDAR Capture Process

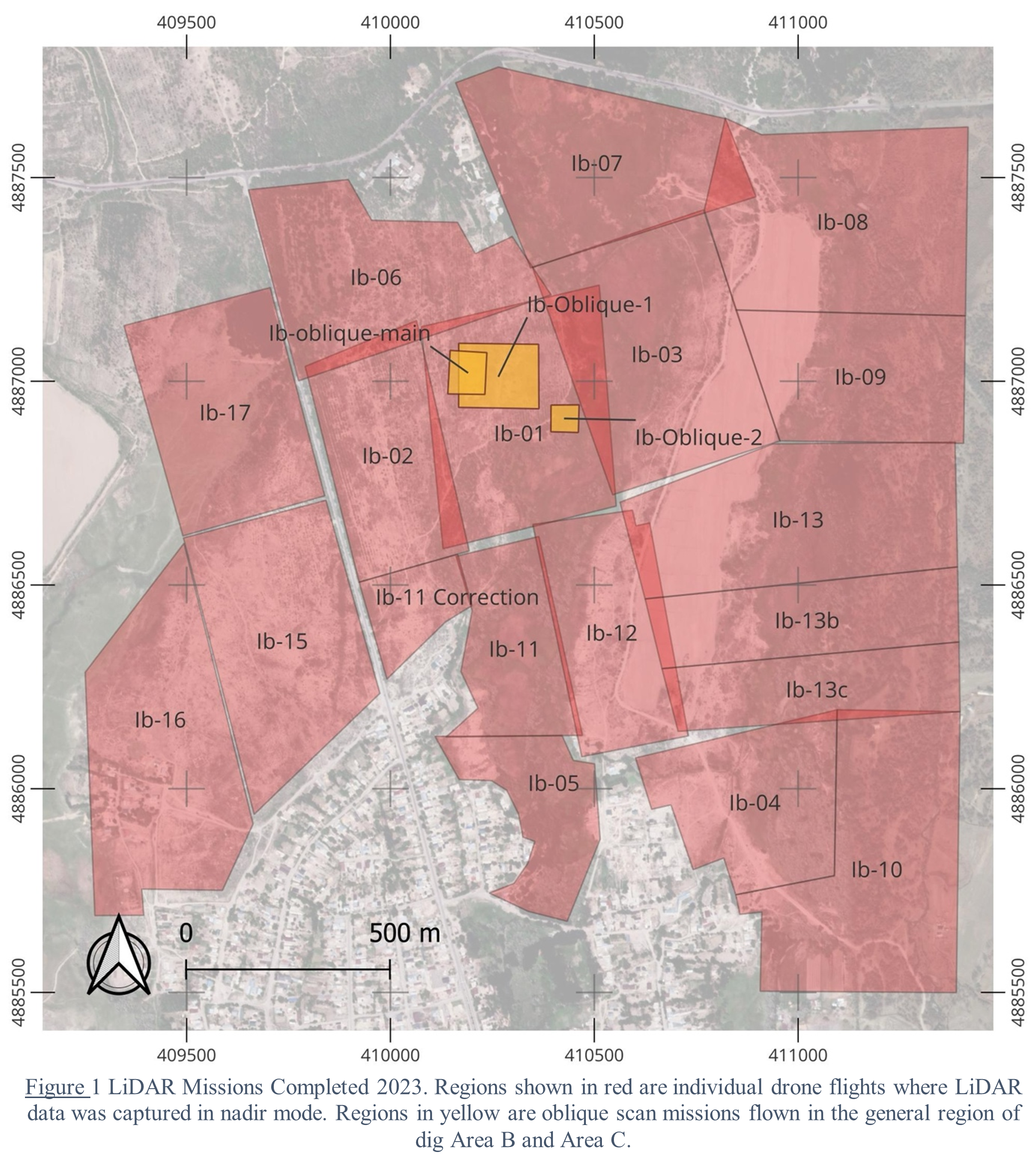

In total, 20 LiDAR scanning missions were completed over the course of a week, concurrent with the 2023 dig schedule. The scanned area covered approximately 3.7 square kilometers surrounding the excavation site. See Figure 1 for a map of the planned missions.

Flight missions were set to capture either nadir or oblique scans of the terrain. Nadir scans (the majority of missions flown) involve pointing the LiDAR scanner directly downward so that the laser pulse direction is generally perpendicular to the scanned surface below. Oblique scans set the laser pulses at an oblique angle (e.g. 45°) to the scanned surface, such that the LiDAR unit is essentially looking at its subject from the side. The oblique scan mission consists of five flights of the subject area, four from the cardinal directions observing the subject from an oblique angle, and one from a nadir position. The five resulting point clouds are then merged post-process into a single model yielding more clarity of the three-dimensional characteristics of the object. Oblique missions were flown to scan the immediate dig site, once in the middle of the expedition, and once at the end.

Data Processing and Analysis

Proprietary software DJI Terra was used to provide initial processing of the raw data recovered from the LiDAR unit post-flight. The primary function of this initial processing is to apply either the real-time kinematic (RTK) GNSS corrections or the post-process kinematic (PPK) GNSS corrections to the point cloud, increasing the GNSS precision of each point from a few meters to a few centimeters.

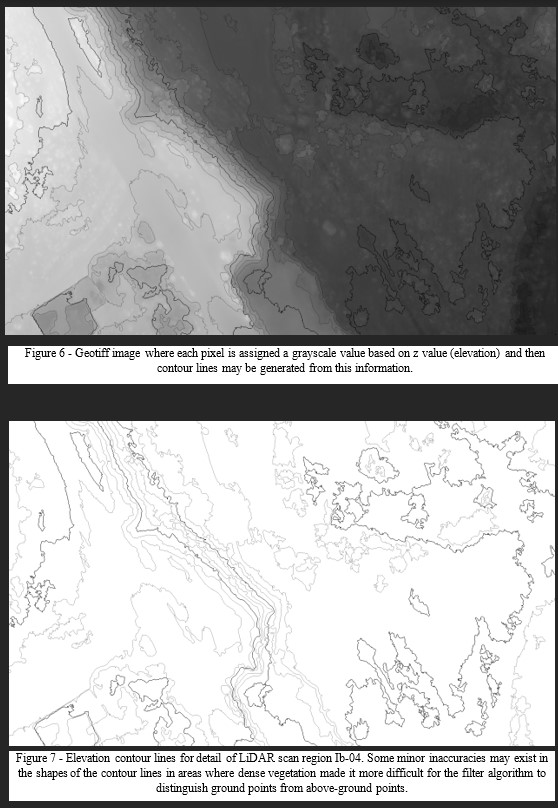

Once the raw data was processed, it was exported to a non-proprietary point cloud format for further analysis with other point cloud and GIS software tools. This specialized software offered the ability to visualize and manipulate point cloud data in various ways. For our purposes, primarily four capabilities were utilized: 1) filtration of point cloud data to distinguish ground plane points from above-ground objects, 2) scalar colorization of the model’s z-axis data for visual identification of ground surface anomalies, 3) generation of contour plots from which topographic maps could be created, and 4) distance, location, and geometry reporting.

As the primary interest in employing LiDAR on this project was the analysis of the ground surface shape or topography, a first step in processing the point cloud was to utilize specialized algorithms that could distinguish “ground points” from “above ground points.” The result of this process yields a point cloud where much of the vegetation points are removed and visualization and analysis of the ground surface can proceed with more clarity.

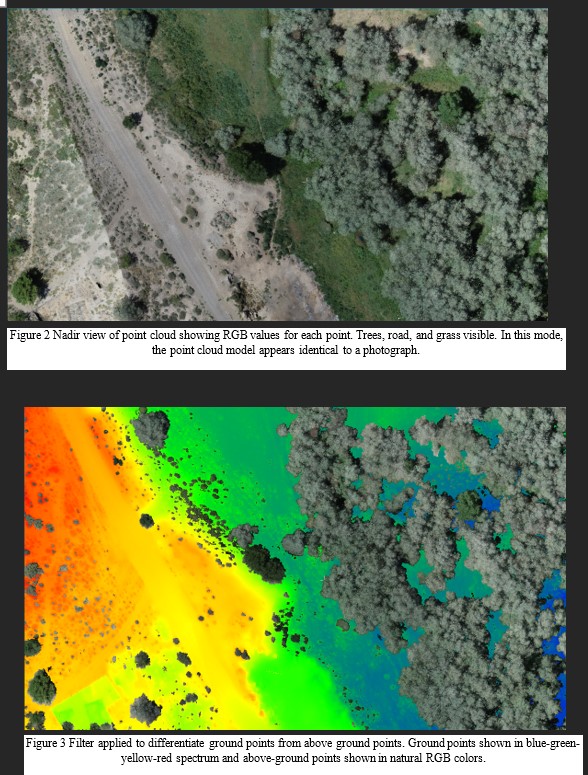

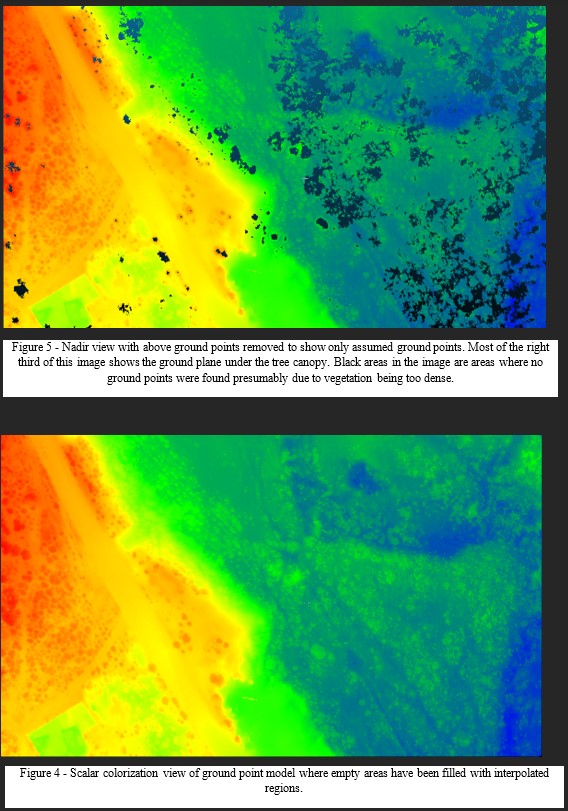

The images below (Figures 2 through 4) illustrate this part of the process. Figure 2 is a top view detail of the resulting RGB colored point cloud from scan Ib_04. Note the location of the trees in this view. Figure 3 is the same location on the same scan, but where CloudCompare has attempted to differentiate points representing the ground plane from points representing above-ground elements (vegetation, buildings, etc.). Figure 4 shows the same view, but this time with the above-ground points hidden to show the density of point information at the ground plane. Note that in this area of the model even under the tree canopy, it is possible to fully comprehend the shape of the ground plane. (Note that this level of ground plane topography information is non-existent in photogrammetry generated models).

Scalar Field colorization is rendering a point cloud such that each point is colorized on a given spectrum based upon some predetermined type of information about that point. For example, a point cloud might be rendered on a spectrum of blue to green, where dark blue points have the lowest z-value (elevation), and bright green points have the highest relative z-value (elevation). Such a rendering visually illustrates areas of the model which are higher or lower based on the color, even if one is viewing the model from above. Scalar colorization was heavily utilized during visual analysis of the Ilibalyk LiDAR scans.

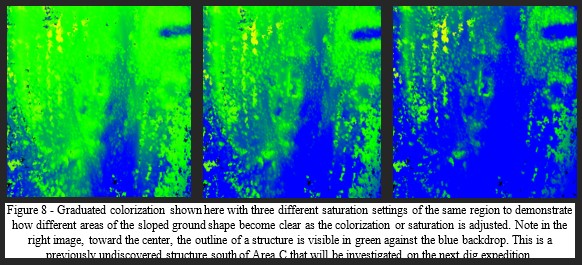

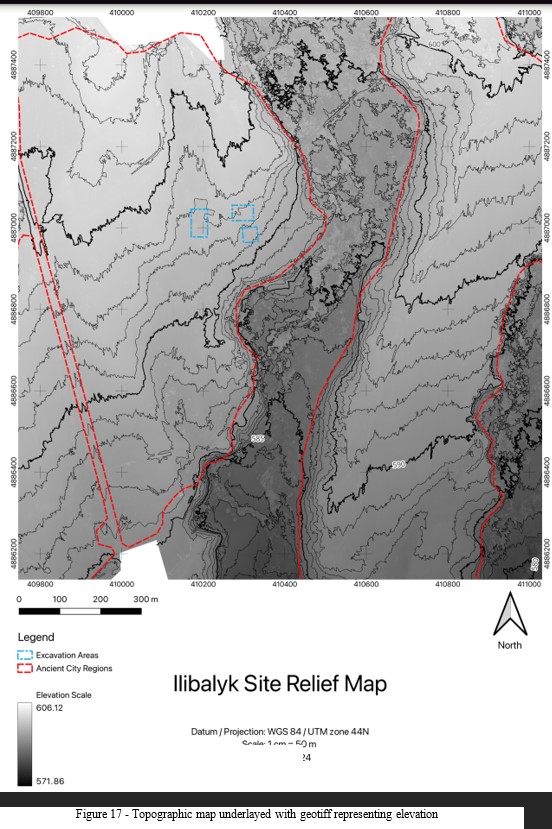

Ilibalyk was located on a topographic plane that slopes gently downward to the south. Moreover, the creek in the middle of the site means a depressed region along the center of the ancient city. In the case of field IV of the excavation site, the slope is both to the east (the creek) and the south. Including the entire area scanned with LiDAR during the 2023 expedition, there was an overall difference in elevation from highest to lowest point of over 30 meters across nearly 2.2 km horizontal distance. The significance of this during analysis of the point cloud data using scalar field colorization is that a sloped site will display a spectrum of color merely by nature of one end being higher and one lower, distracting from color differentiations that would indicate local features of the surface shape. Consequently, to visually exaggerate surface anomalies on a sloped ground plane, the color spectrum parameters must be adjusted for each respective section of the sloped ground plane moving from north to south or vice versa. This is illustrated in the images of Figure 8.

Interpretation and Results

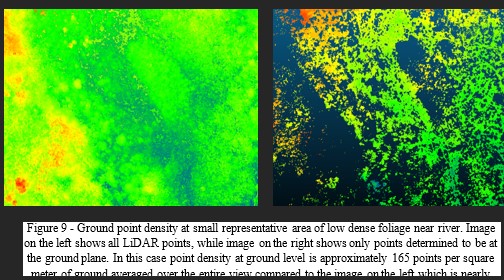

Scan regions Ib-03 and Ib-07 (refer to map above) represent regions that are heavily covered in dense low foliage. Figure 9 shows the filtered ground points in a small representative area of region Ib-07. The point density of the ground points in this region is 165 points per square meter. This contrasts to some areas with tree coverage (high foliage) which has a higher average point density of 215 points per square meter. The whole model density (ground and above-ground points) is as high as 1500 points per square meter. The result is that any interpolated ground form in dense foliage areas has relatively low reliability. It is possible to locate the ground elevation due to the fewer points that are captured at the bottom of the foliage but point density at the ground plane is too low to reconstruct the ground form in such a way that would display shape characteristics of value for our uses. This may not be entirely problematic in all cases. These densest areas of vegetation are generally found at the lowest part of the valley along the river. As our primary interest is finding new areas of the populated rabad for excavation, we can assume that these densest foliage areas are too low in the flood plane of the river to be a realistic location for most human-made structures. Should it be determined that there is value in obtaining a ground plane model with higher reliability in these low, dense foliage areas, additional LiDAR scanning should be conducted in the fall months after most leaves have fallen.

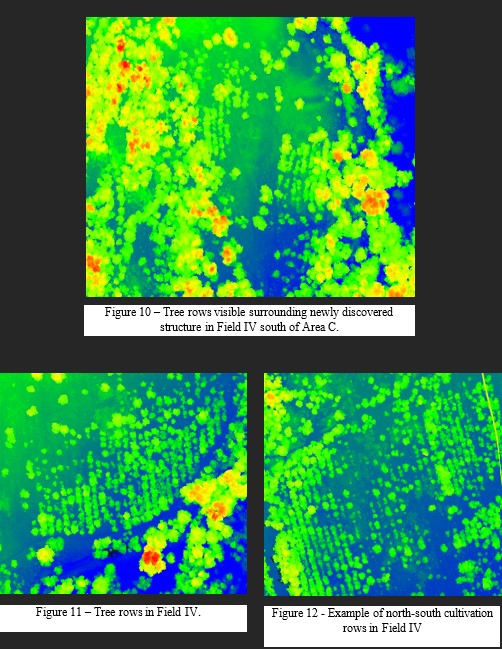

Agricultural activity from the previous two centuries in the vicinity of the medieval Ilibalyk site has re-textured the ground surface over a large portion of the overall area scanned. In the region immediate to Field IV, satellite and aerial photography reveal a discernable pattern of cultivation rows oriented generally north-south, parallel to the direction of slope. See Figure 12, Figure 11, and Figure 10. Measurements of the LiDAR model in these areas indicate an average row to row width of approximately 3.5 meters. The shape of the ground plane corresponds with the visible lines of trees. The ground texture in these areas is a clear ridge-and-furrow pattern on 3.5 meter centers with trough-to-crest elevation difference typically between 10 and 30 centimeters.

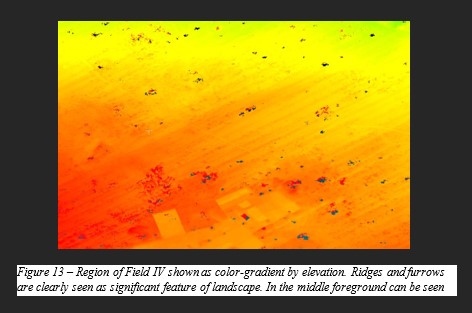

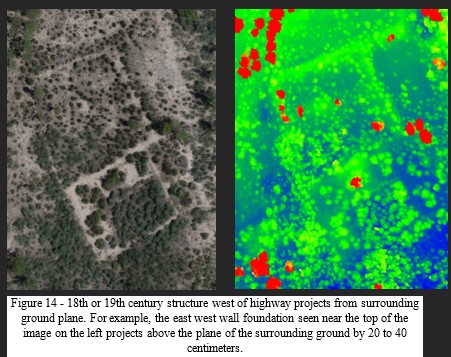

Given that our main objective in employing LiDAR on this project is to aid in finding locations of medieval structures below ground, it is important to consider how this ridge and furrow ground texture hinders us in this task. Figure 13 employs scalar field colorization to help visualize the ridge and furrow texture of the ground around Areas A and B. The orange striations in the image are the 10 to 30 cm elevation difference from furrow to crest mentioned above. Now consider the structure foundations from the 18th and 19th centuries known to exist sub-surface from in the region to the west of the highway (see field report from 2016). At these locations, the ground surface at the presumed structure location projects slightly above the surrounding grade. We can measure the amount of this projection and compare it to the ground surface re-texturing in the cultivated regions of Field IV. Such a comparison suggests that the dimensions of the furrows in regions such as Field IV are sufficient to obscure indications of structures that might otherwise be discoverable with LiDAR data analysis. Put differently, the furrows are deep enough that they would theoretically erase otherwise noticeable surface traces of structures where they occur. Figure 14 shows an aerial photo and color gradient view of a structure assumed to be from the 18th or 19th centuries located west of the highway. The greatest elevation difference between surrounding ground level and level on top of foundation is approximately 40 cm. The ridge and furrow ground texture in Field IV may potentially be preventing our detection of similar underground structures that may exist there.

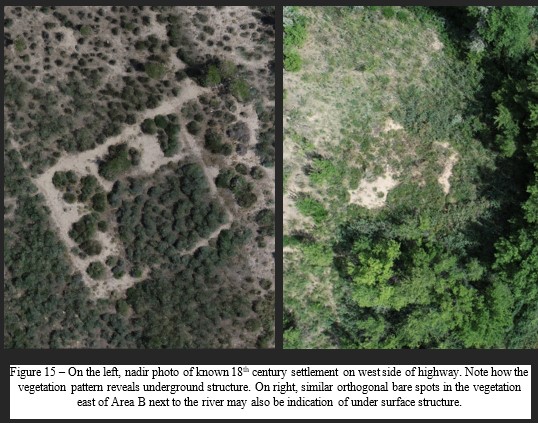

Analysis of the aerial photography that was captured during the LiDAR scan process may have yielded another approach for determining location of sub-surface structures. Nadir photographs taken in the 18th/19th century area west of the highway reveal a distinctive pattern in the distribution of plant growth in certain places. It may be hypothesized that the bare areas in these images (see Figure 18) are due to underground structures. The orthogonal arrangement and length of these bare areas suggest the presence of foundation walls for either enclosed structures or stand-alone walls. Notably, Figure 15 shows how an area in Field IV shares similar characteristics to the afore mentioned area west of the highway. The image on the right is located east of dig Area B, adjacent to the river. A discernable rectangular shape rotated slightly to the east may be inferred from ground vegetation pattern. Further examination of plant distribution and growth as seen in the aerial photography may offer additional insights, guiding the identification of areas warranting further investigation.

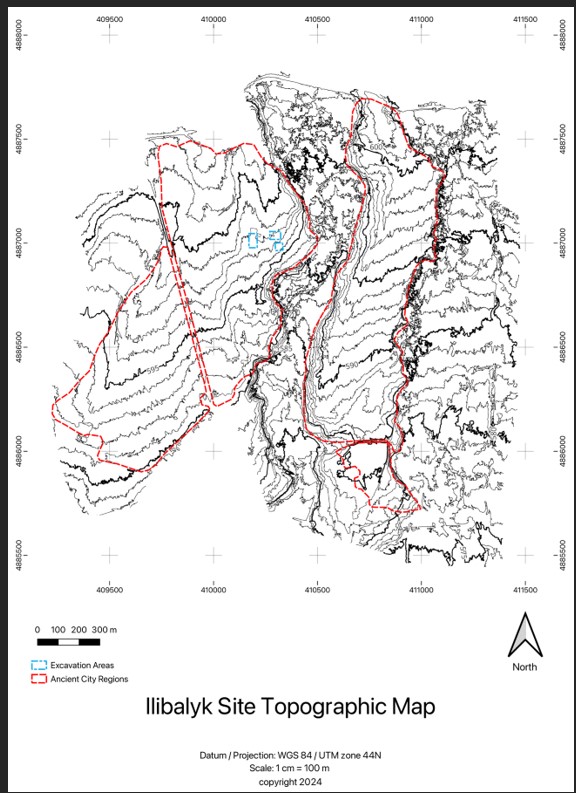

LiDAR data captured in 2023 was used to create detailed topographic maps. These maps allow us to analyze the physical landscape of Ilibalyk, providing insight into its layout, infrastructure, natural features, and relationship to the river. For example, we are now able to understand more clearly the locations and routes of the irrigation channels located throughout the scanned area.

Figure 16 - Topographic map generated by processing LiDAR data from 2023 scans of Ushural/Ilibalyk region

Other Considerations

Commercial utilization of remotely operated flying systems in Republic of Kazakhstan airspace is governed by Order No. 706 of the Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure Development from 2020 and subsequent revisions (The ministry was reorganized and divided in 2023 into the Ministry of Transportation and the Ministry of Industry and Construction). The dig team endeavors to be compliant with all local and federal regulations regarding the registration and use of unmanned aerial vehicles whether for the purpose of LiDAR scanning or photogrammetry. See bibliography for links to official regulation sources.

Conclusion

The LiDAR scan activities during the 2023 expedition provides precise and high-resolution data for analyzing ground surface characteristics. The technology's ability to penetrate vegetation offers a distinct advantage over other methods like photogrammetry, particularly in areas with dense shrubbery and trees. Analysis of the LiDAR-generated point clouds is facilitating the identification of potential anomalies indicative of sub-surface structures. While agricultural reshaping of the ground surface reduces the usability of the data in many areas, the LiDAR data is providing valuable insights for ongoing excavation efforts. Integration of LiDAR technology into the archaeological investigations at Ilibalyk is offering a nuanced understanding of the site's overall topography adding to our understanding of how the settlement in this area was organized, and its relationship to the river. The point cloud data captured in 2023 will continue to be analyzed with various visualization and filtering techniques with the purpose of potentially leading the team to new areas for excavation.

Bibliography for LiDAR Report Section

- Утверждены правила эксплуатации беспилотных летательных аппаратов в воздушном пространстве Республики Казахстан https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=38097460

- Как можно использовать дрон в Казахстане — в МИИР напомнили правила https://www.zakon.kz/tekhno/6015766-kazakhstantsam-napomnili-o-pravilakh-ekspluatatsii-dronov-v-vozdushnom-prostranstve.html

- приказ Исполняющего обязанности Министра индустрии и инфраструктурного развития Республики Казахстан от 31 декабря 2020 года № 706 Об утверждении правил эксплуатации беспилотных летательных аппаратов в воздушном пространстве Республики Казахстан, http://law.gov.kz/client/#!/doc/181230/rus

- Crutchley, S., & Crow, P. (2018). Using airborne lidar in Archaeological Survey: The Light Fantastic. Historic England https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/using-airborne-lidar-in-archaeological-survey/heag179-using-airborne-lidar-in-archaeological-survey/

- Herrera, V. M. (2017). Archaeology et geomatics: Harvesting the benefits of 10 years of training in the Iberian Peninsula (2006-2015). Sidestone Press.

- Štular, Benjamin and Lozić, Edisa. "Airborne LiDAR data in landscape archaeology. An introduction for non-archaeologists" it - Information Technology, vol. 64, no. 6, 2022, pp. 247-260. https://doi.org/10.1515/itit-2022-0001

- Cowley, D. C., & Opitz, R. S. (2012). Interpreting archaeological topography: Lasers, 3D data, observation, visualisation and applications. Oxbow Books.

- DJI Zenmuse L1 User Manual https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/Zenmuse_L1/20210518/Zenmuse_L1%20_User%20Manual_EN_1.pdf

- DJI Matrice 300 RTK User Manual https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/matrice-300/20200507/M300_RTK_User_Manual_EN.pdf

- DJI Smart Controller User Manual https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/smart+controller/20190110-2/DJI_Smart_Controller_User_Manual_EN_V1.0_0110.pdf

- Kersten, T., Wolf, J. and Lindstaedt M., Investigations into The Accuracy of the UAV System DJI Matrice 300 RTK with the Sensors Zenmuse P1 and L1 in The Hamburg Test Field, The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLIII-B1-2022 XXIV ISPRS Congress (2022 edition), 6–11 June 2022, Nice, France, https://isprs-archives.copernicus.org/articles/XLIII-B1-2022/339/2022/isprs-archives-XLIII-B1-2022-339-2022.pdf

Unit and Loci Descriptions

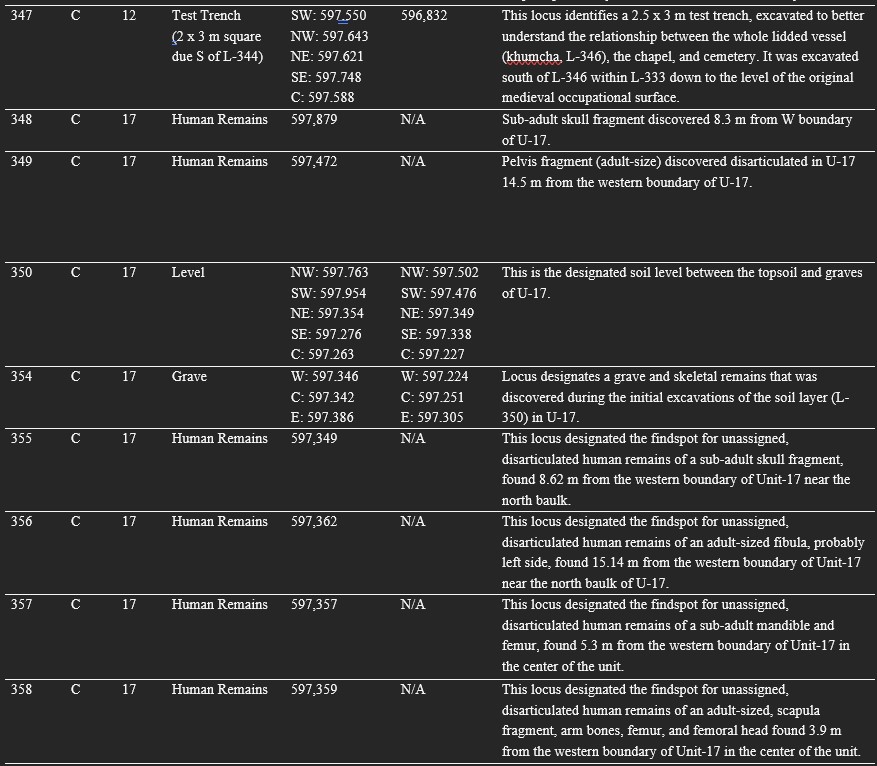

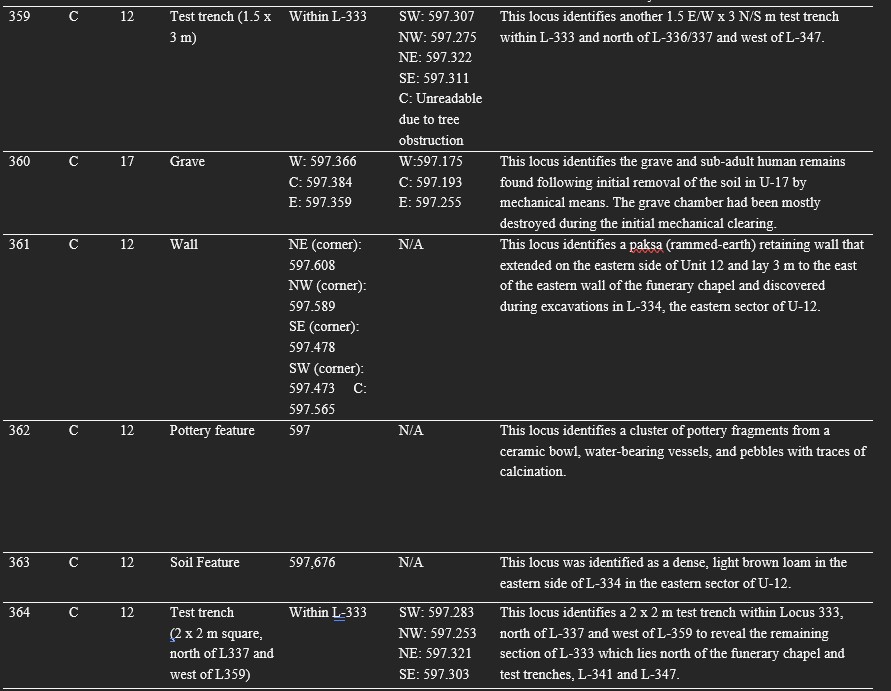

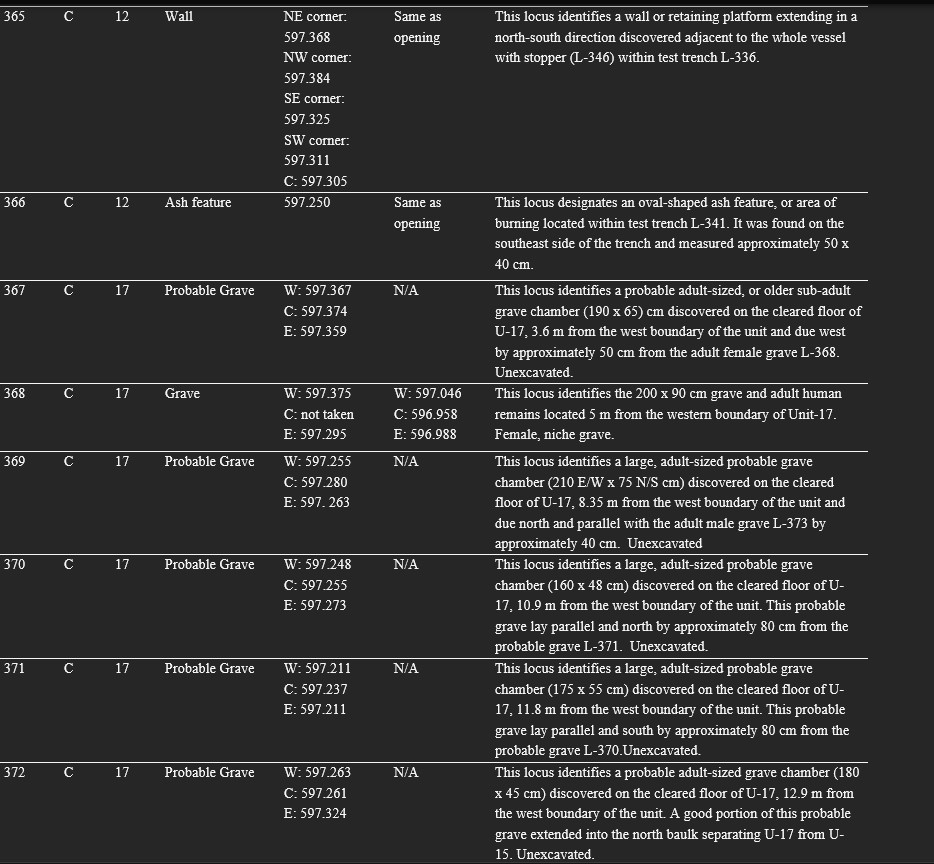

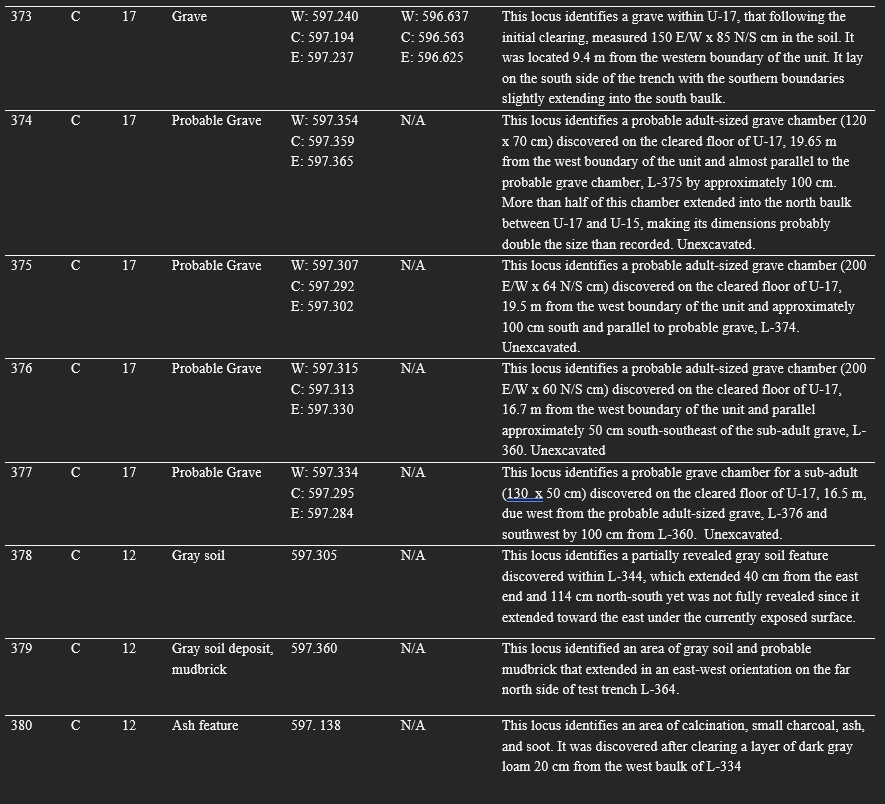

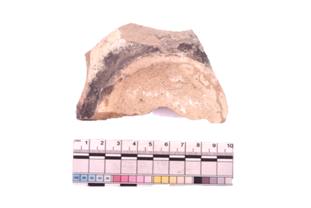

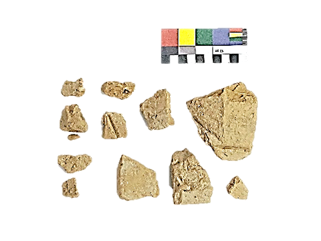

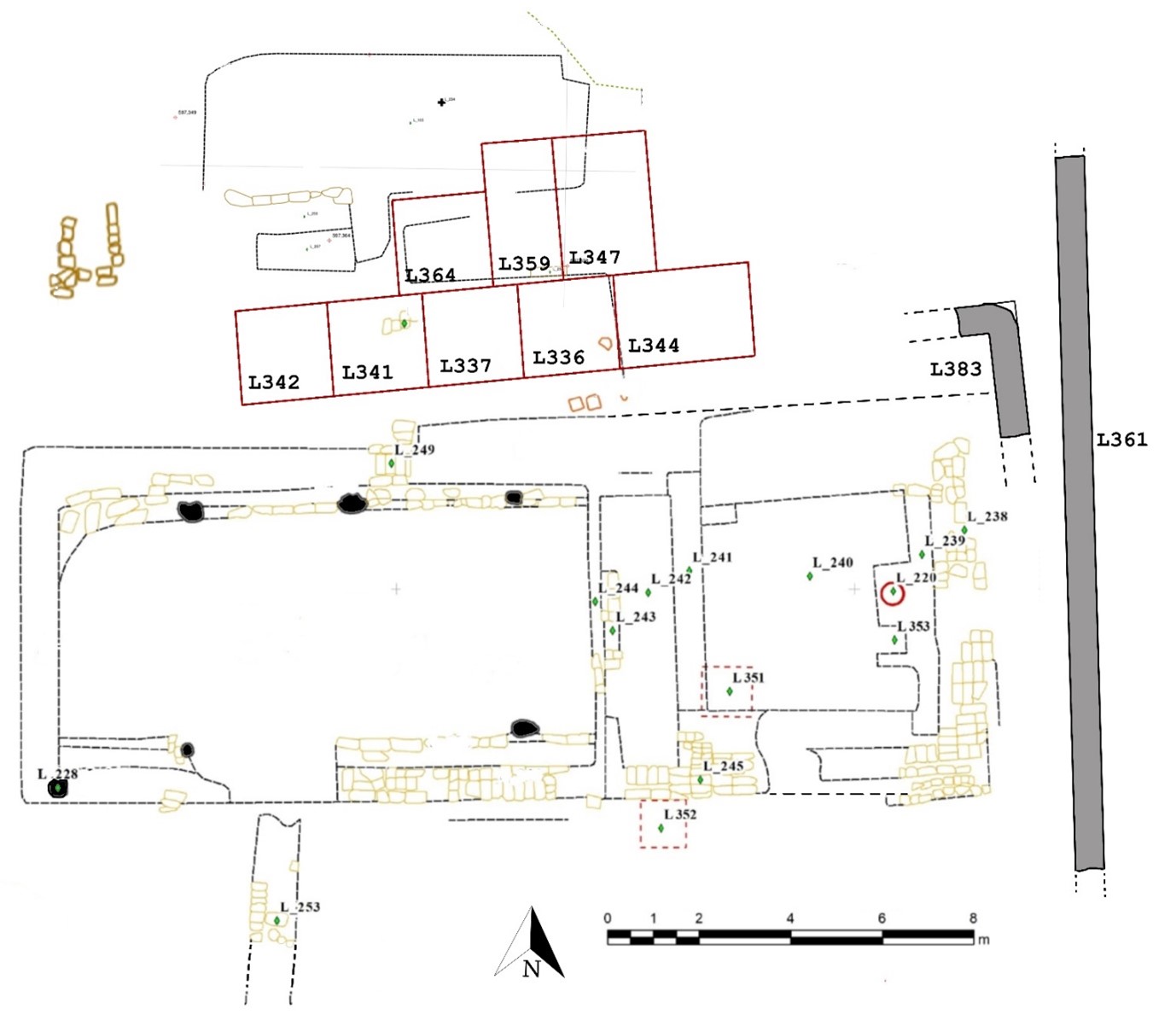

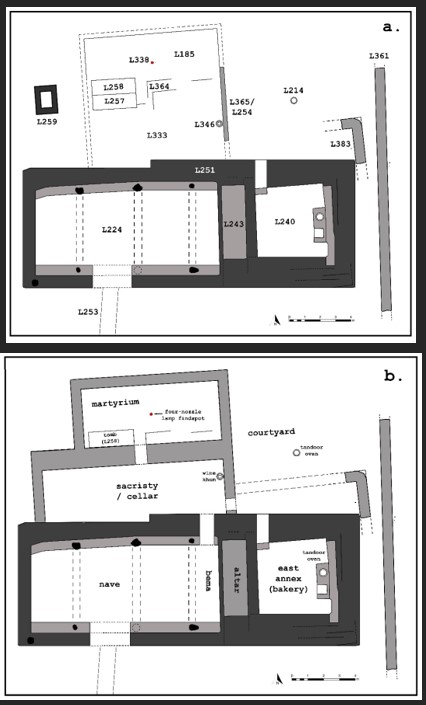

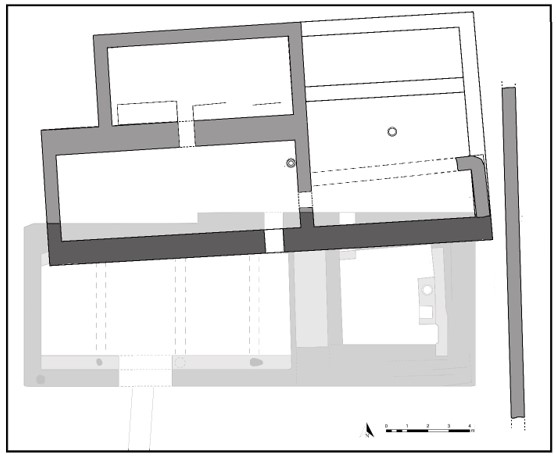

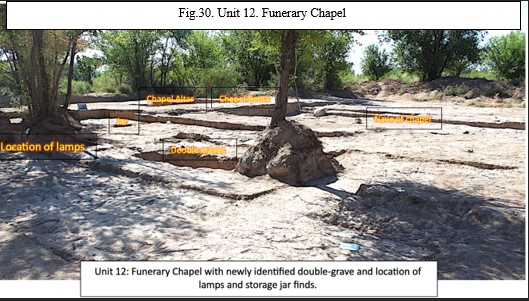

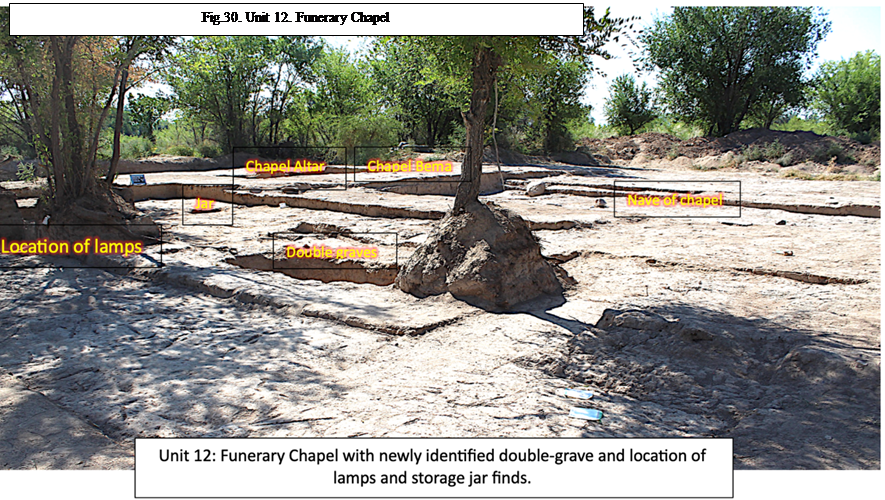

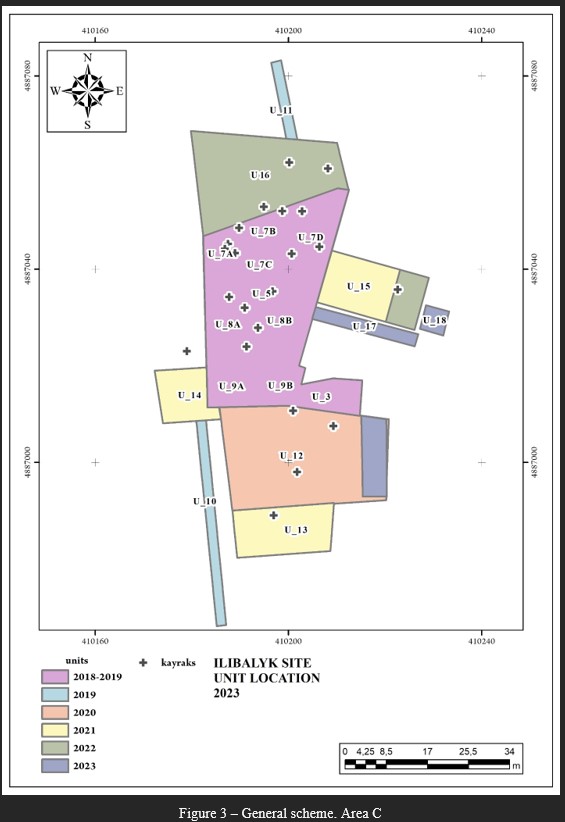

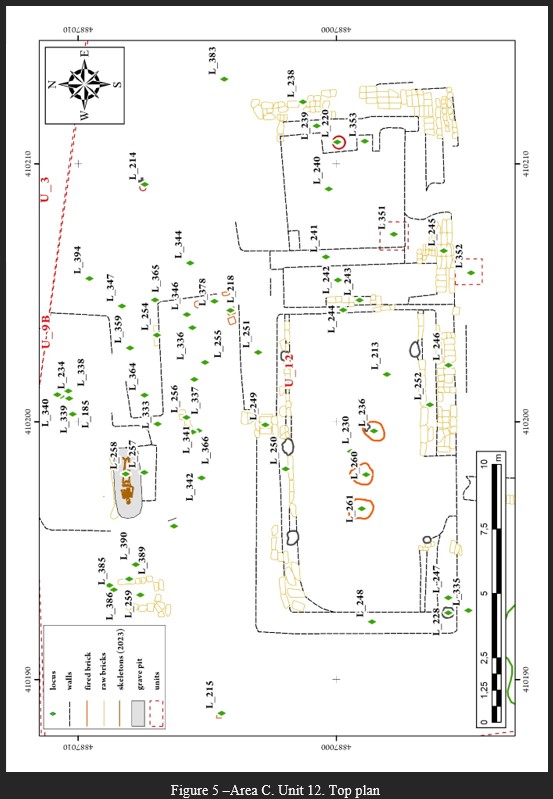

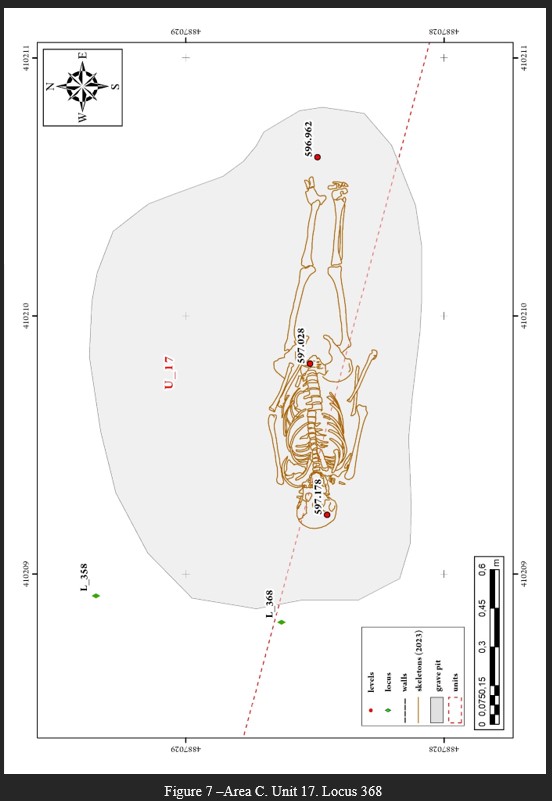

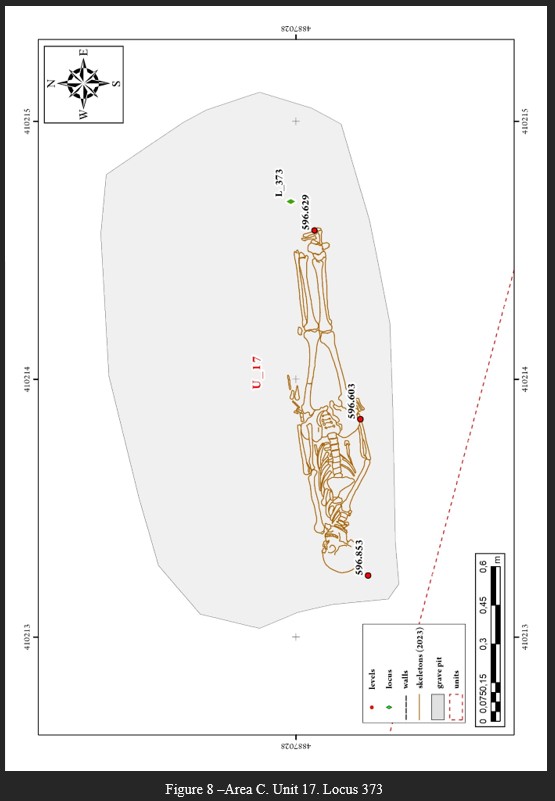

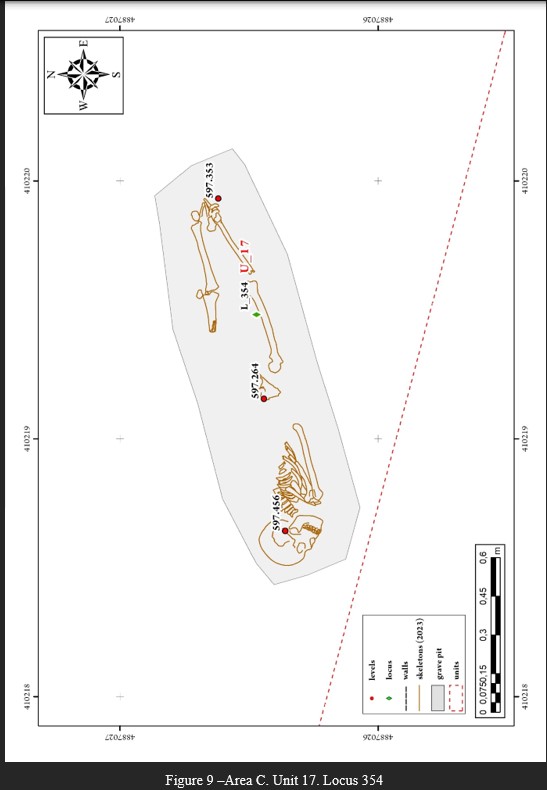

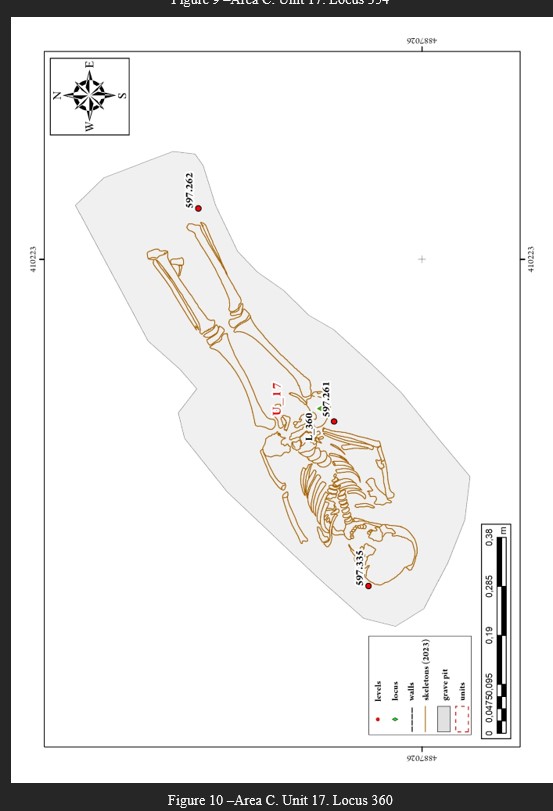

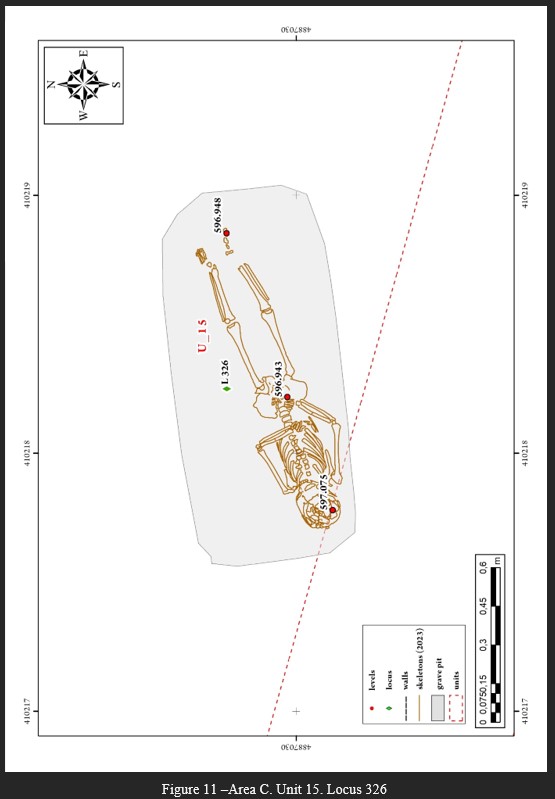

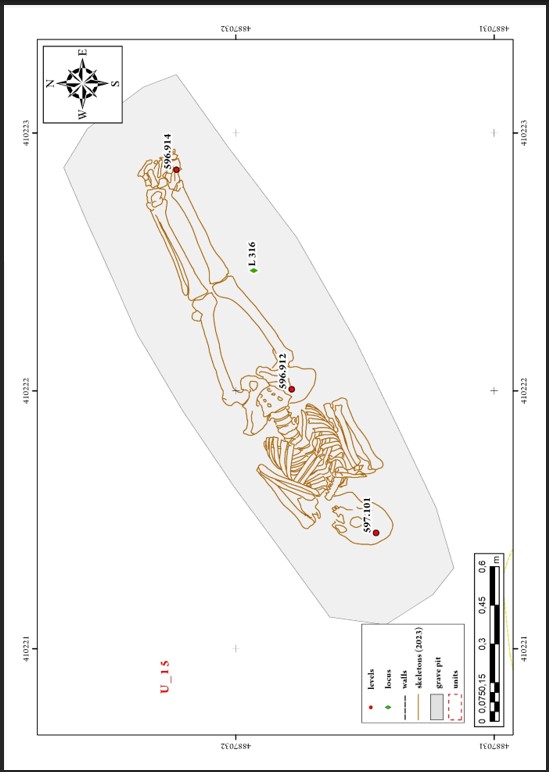

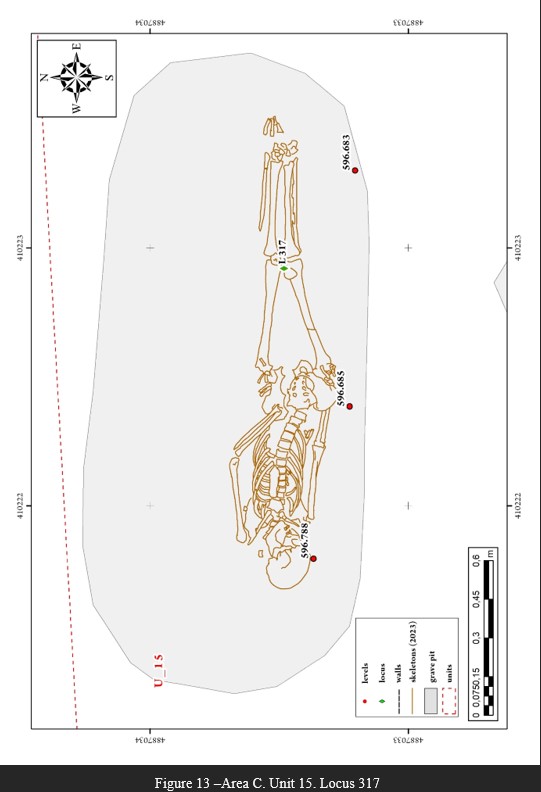

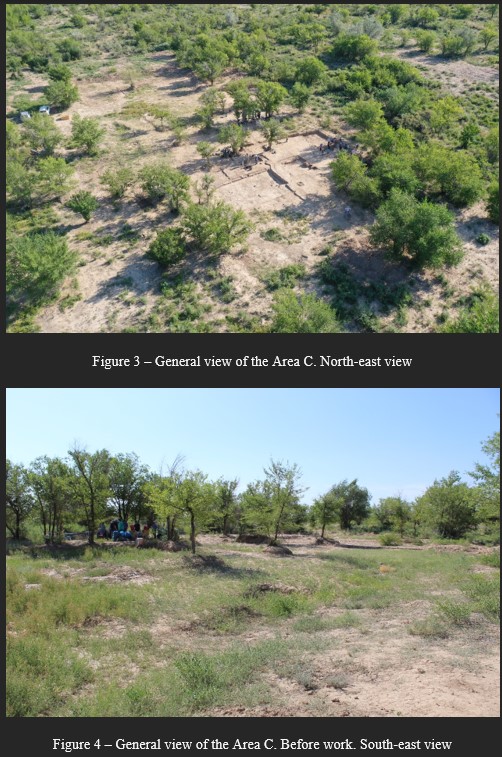

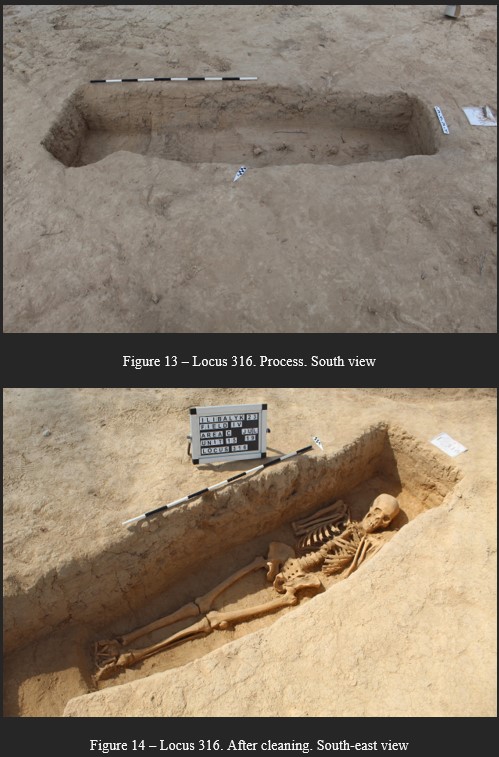

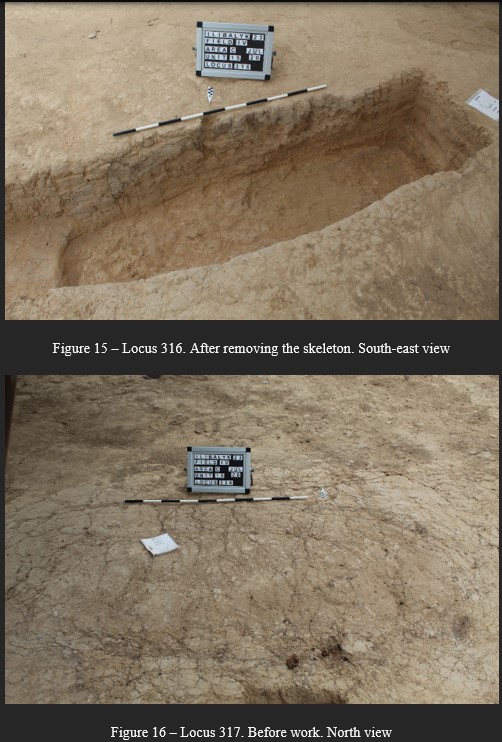

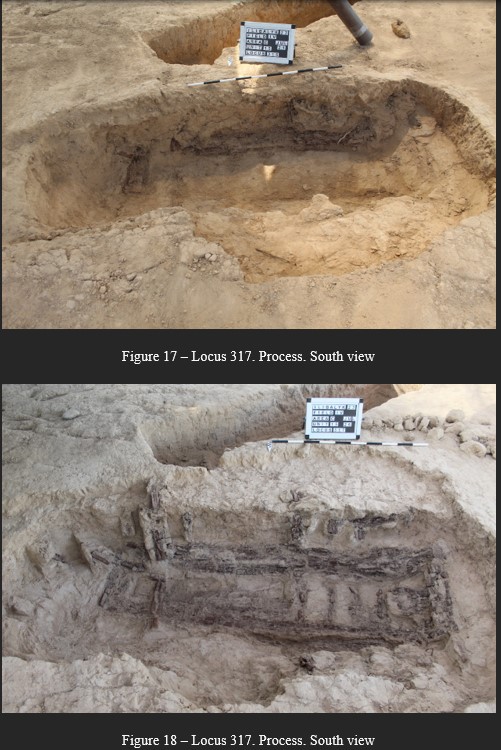

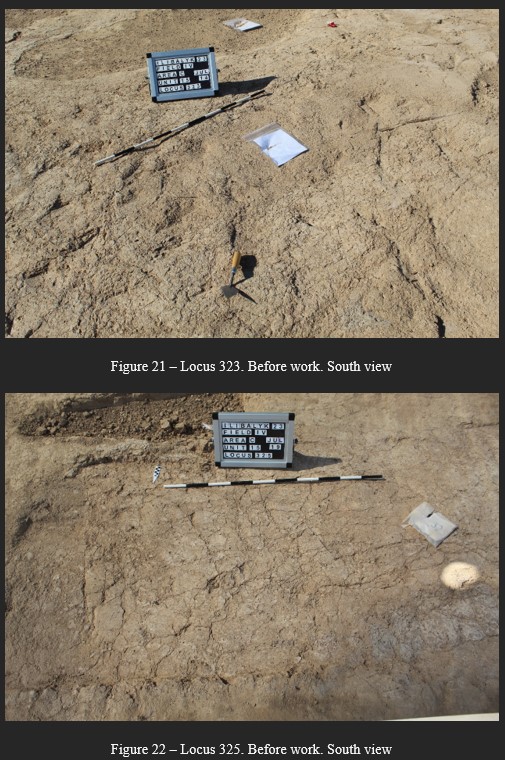

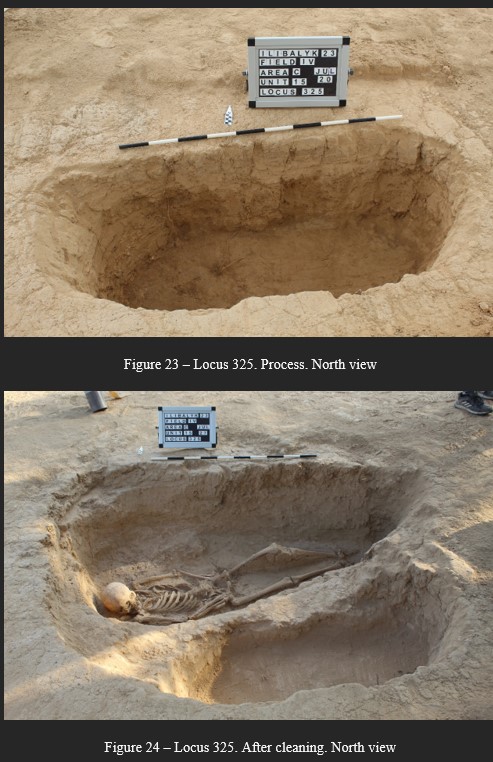

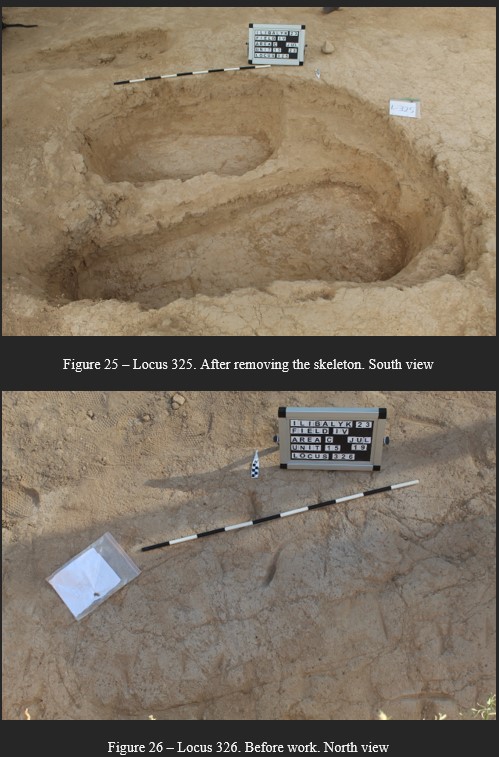

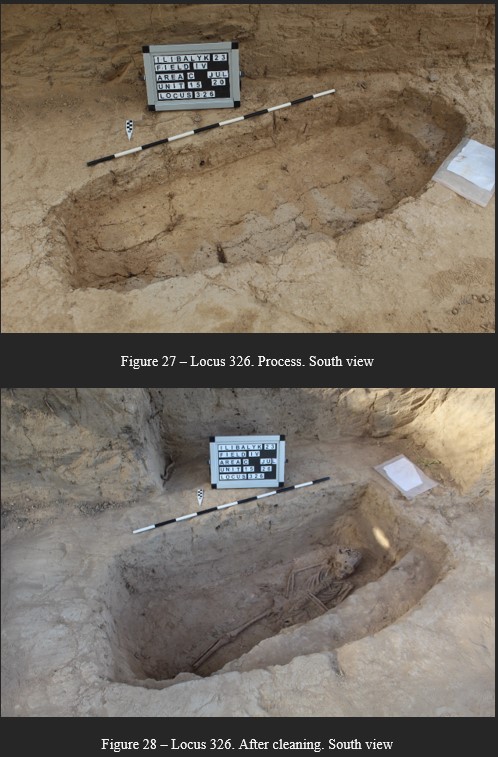

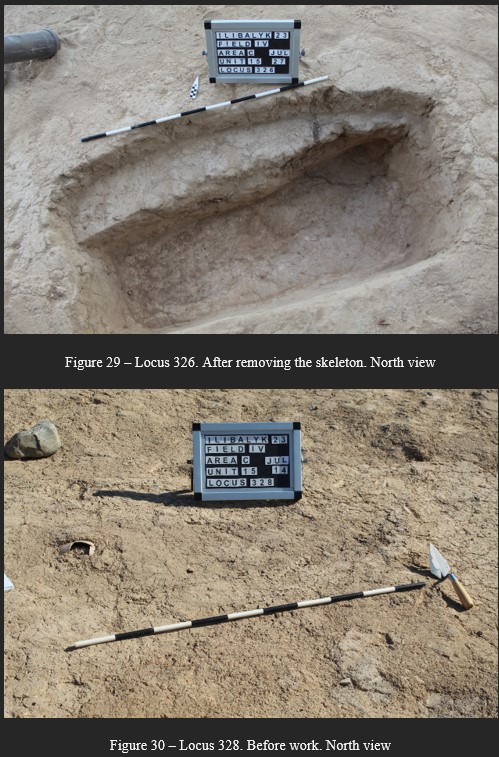

Excavations during the 2023 opened 2 new units (excavation trenches)—specifically Units 17 (23 E/W x 3 N/S m) and 18 (5 x 5 m). Further excavations were conducted in Unit 12—east and north of the previously identified funerary chapel first discovered in 2020—and Unit 15, an area of elite graves initially revealed in 2021. In total, 67 loci were identified, 8 of which had been designated in previous seasons such as graves that had not been excavated. In addition to the 10 graves excavated (1 in U-12, 5 in U-15, and 4 in U-17) an additional 15 probable graves were discovered in which time limitations prohibited further investigation. These discoveries expanded the known boundaries of the cemetery in Area C. In Unit 12 to the north of the northern wall of the funerary chapel as series of test trenches, along with an expansion of L-185, revealed what is currently interpreted as a martyrium that served as a possible northern annex to the chapel, or stood as a separate structure, such as a mausoleum. Excavation on the far east side of U-12, which extended beyond the eastern wall of the chapel, revealed two additional walls, one of which was a possible retaining wall for the eastern half of the structure (L-383) and the other (L-361) which may be from an earlier construction phase of an unknown building and extended the length of the unit along its north-south axis. (Appendix “Photos”. Fig. 1-4)

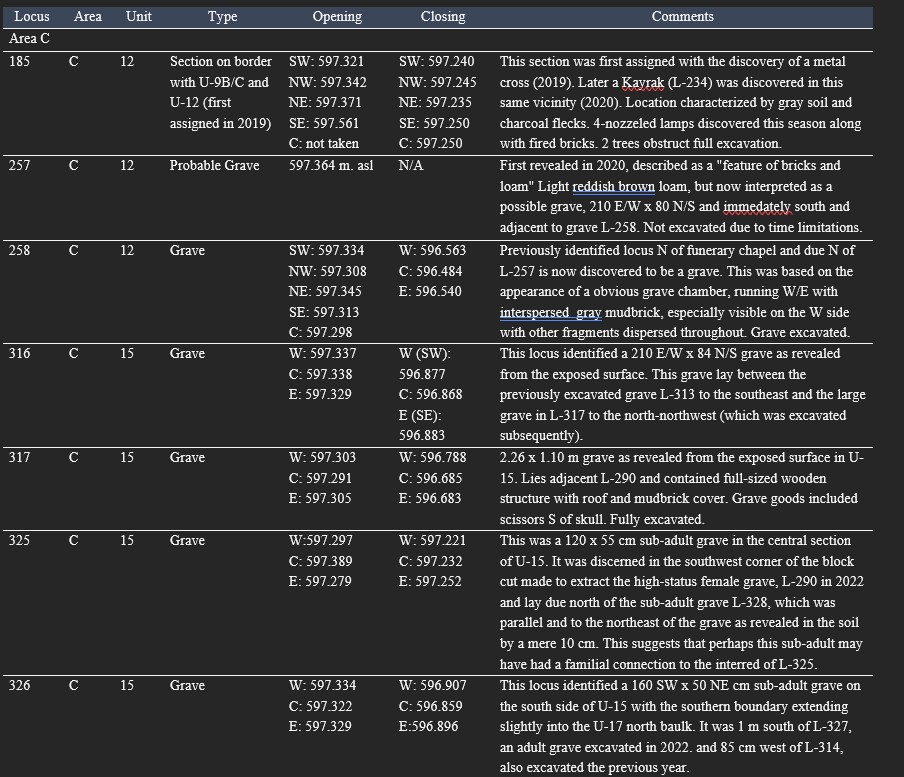

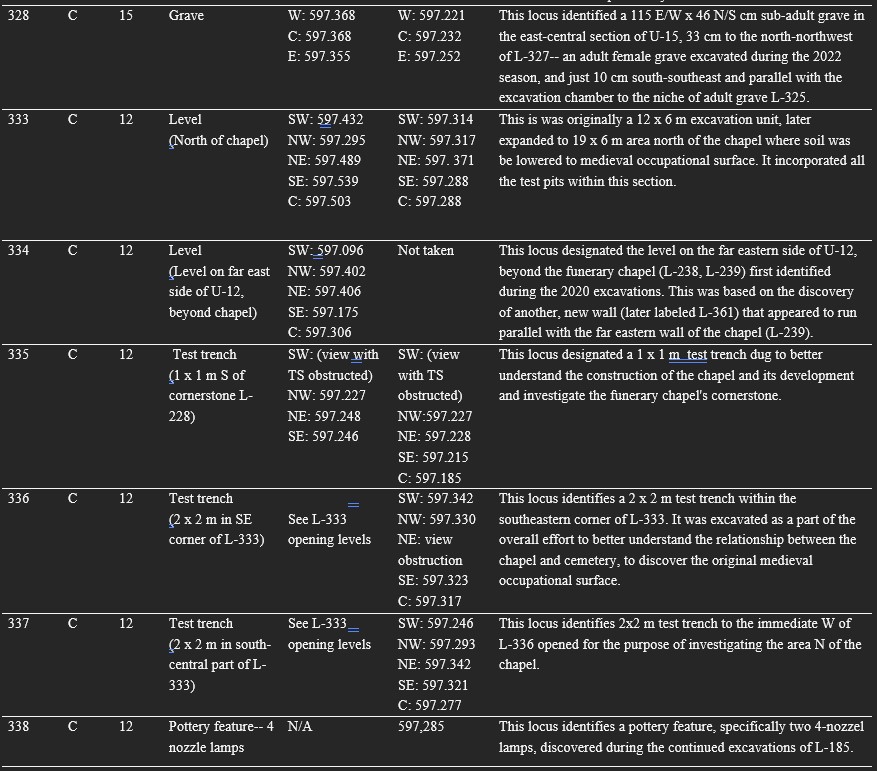

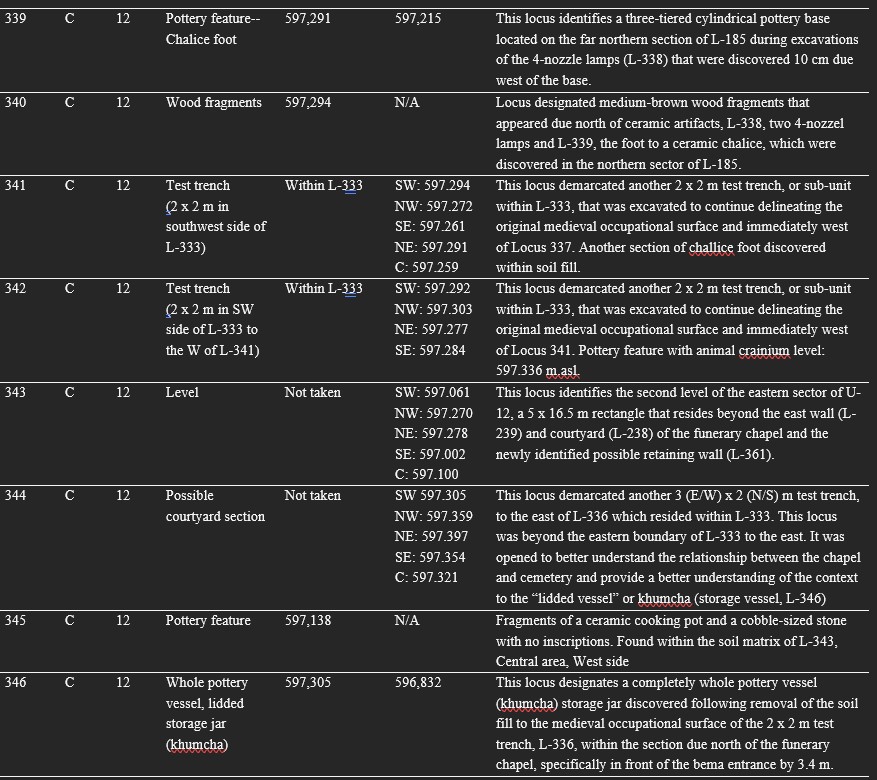

The following loci descriptions are grouped according to their excavation units in numerical order. All these loci are within Field IV, Area C. (Appendix “Drawings”. Fig. 1-5).

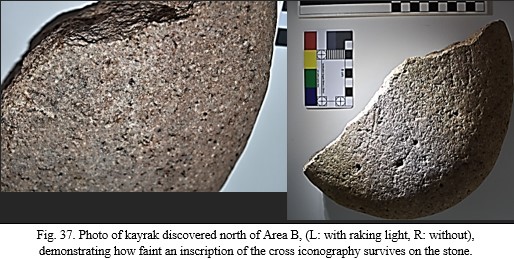

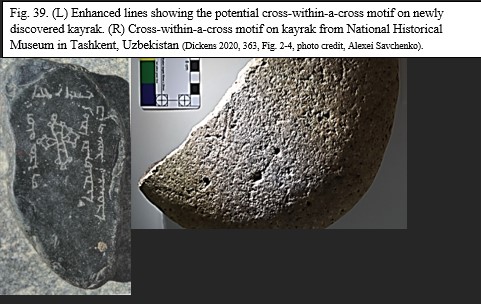

Unit 12

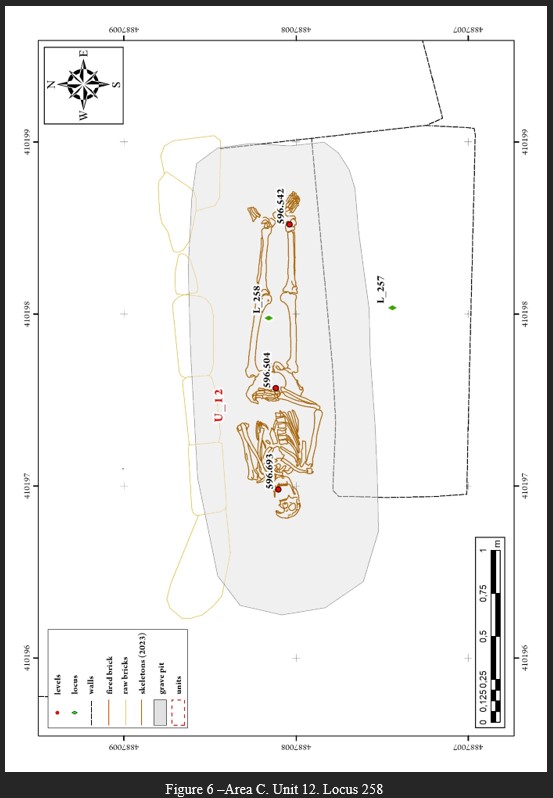

This unit was first excavated in 2020 and was initially delineated as a 32 E/W x 22.5 N/S m area, which at the time, was the most southern boundary of the excavation in Area C. The 2020 excavation revealed what is currently interpreted as a funerary chapel (See 2020 Field Report, pp. 70-77; 2021 Field Report, pp 5-6, and 2022 Field Report pp. 115-127). Cultural material finds and the architectural layout (E/W orientation, identified nave and altar area) continue to affirm the ecclesiastical identification of this structure. The 2023 excavation objectives involved further investigation of the area north of the chapel, specifically Locus 185, from which significant cultural finds, including a metal cross, glaze ware pottery, and a kayrak (L-234), were discovered. Excavators surmised that this section’s area needed to be lowered by several centimeters to better discern this northern section’s relationship to the chapel. In addition, 2 loci (L-257 and L-258), characterized as rectangular shaped features but indeterminate as to function called for closer examination. The results, as detailed below, exceeded expectation with the discovery that Locus 258 was a grave of high status and contained within the possible martyrium and L-257 a possibly grave laying adjacent and parallel with L-258. Due to safety concerns that arose in excavating these two graves that were immediately next to each other, excavation of L-257 was delayed for potential excavation in a future season. Additional graves in and around these two main graves were also detected but are currently obstructed by trees (Appendix “Drawings”. Fig. 6).

As when first discovered in 2020, the chapel area at the conclusion of each season’s excavations had been covered with geotextile to preserve the mudbrick and paksa (tamped earth) wall foundations. This has proven quite effective as the revealed structures remain in good condition. After sweeping the chapel, a 3-D lidar scan by an iPad Pro was successfully completed to be added to the database. Two artifacts sitting on the nave floor (Locus 230)— the base of a bowl and an animal bone—were cleared and catalogued.

The backfill soil, which created a thick layer upon the geotextile contained a few potsherds, which was expected, yet none of these sherds can provide any diagnostic information or can be considered even from the soil matrix since this backfill soil has been removed and replaced several times.

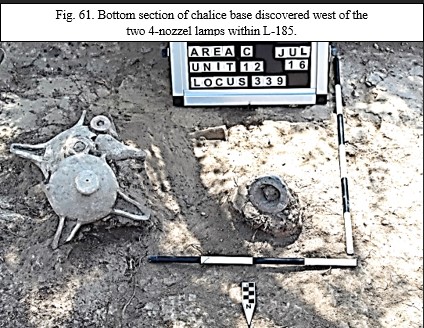

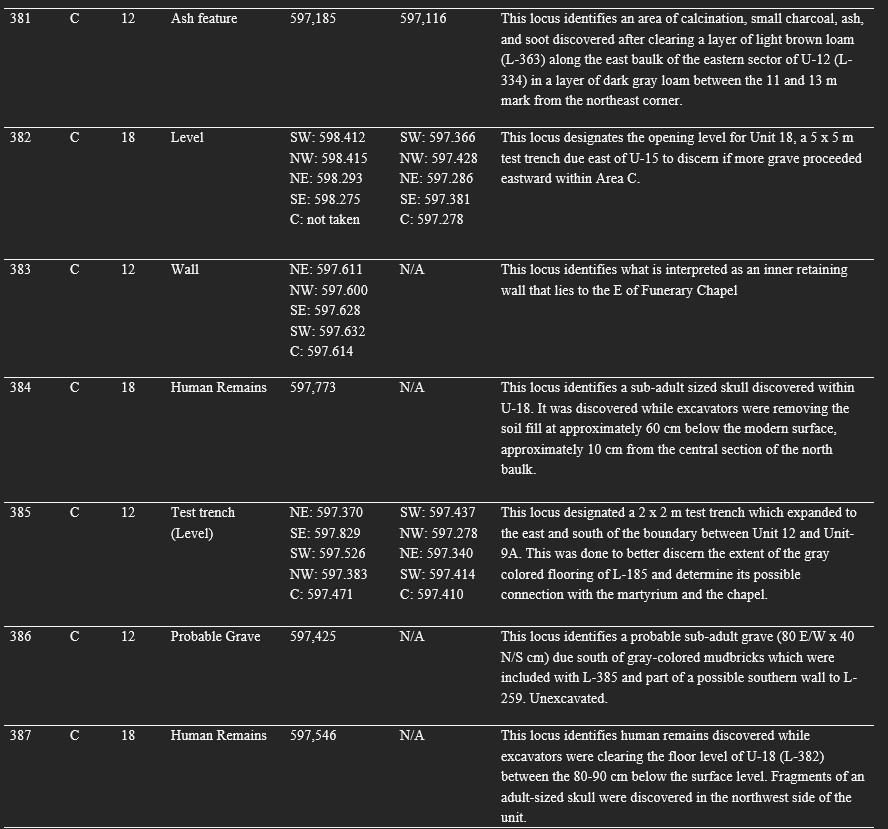

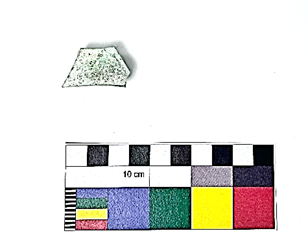

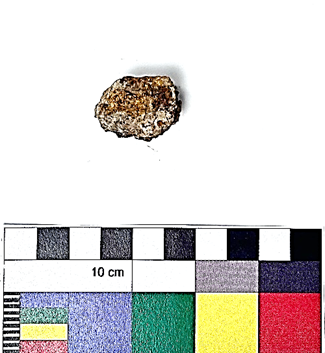

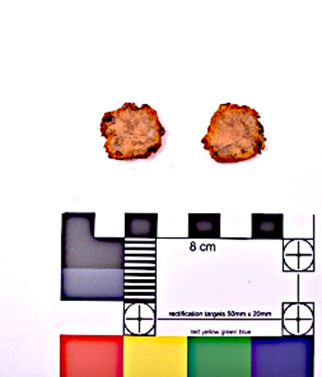

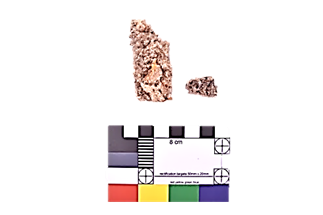

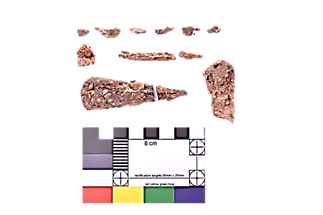

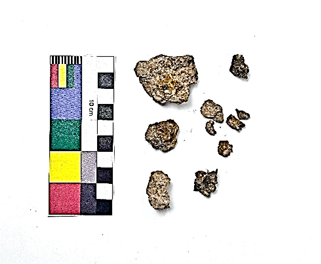

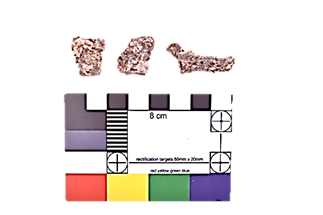

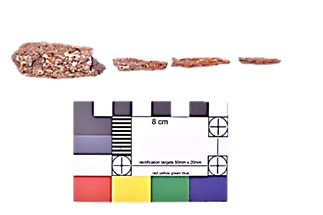

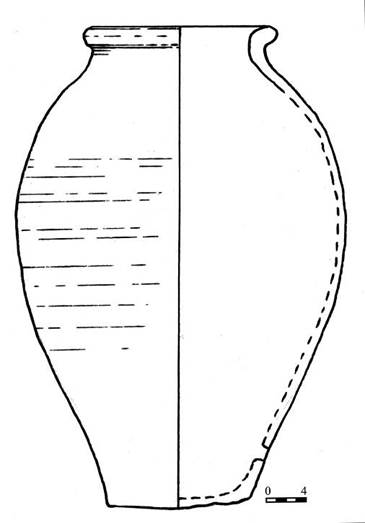

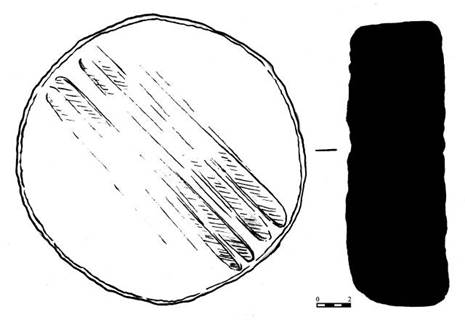

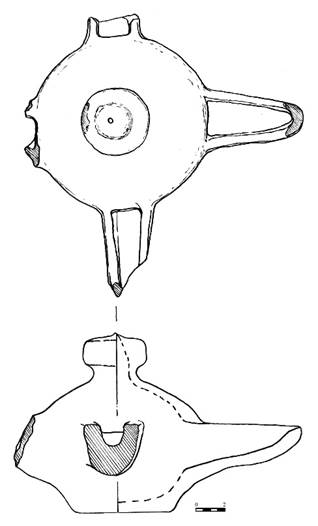

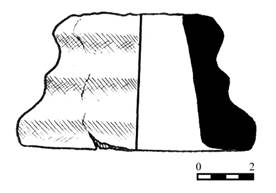

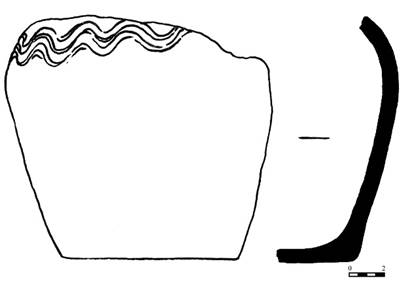

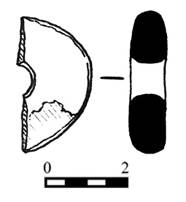

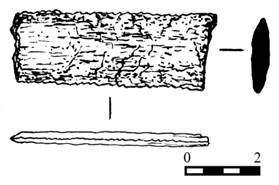

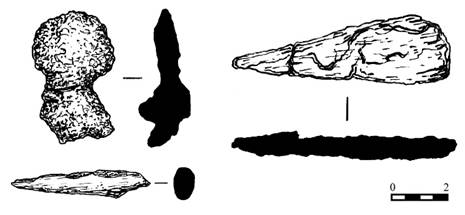

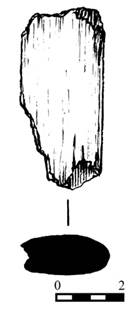

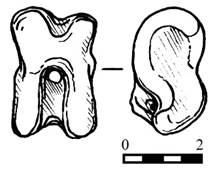

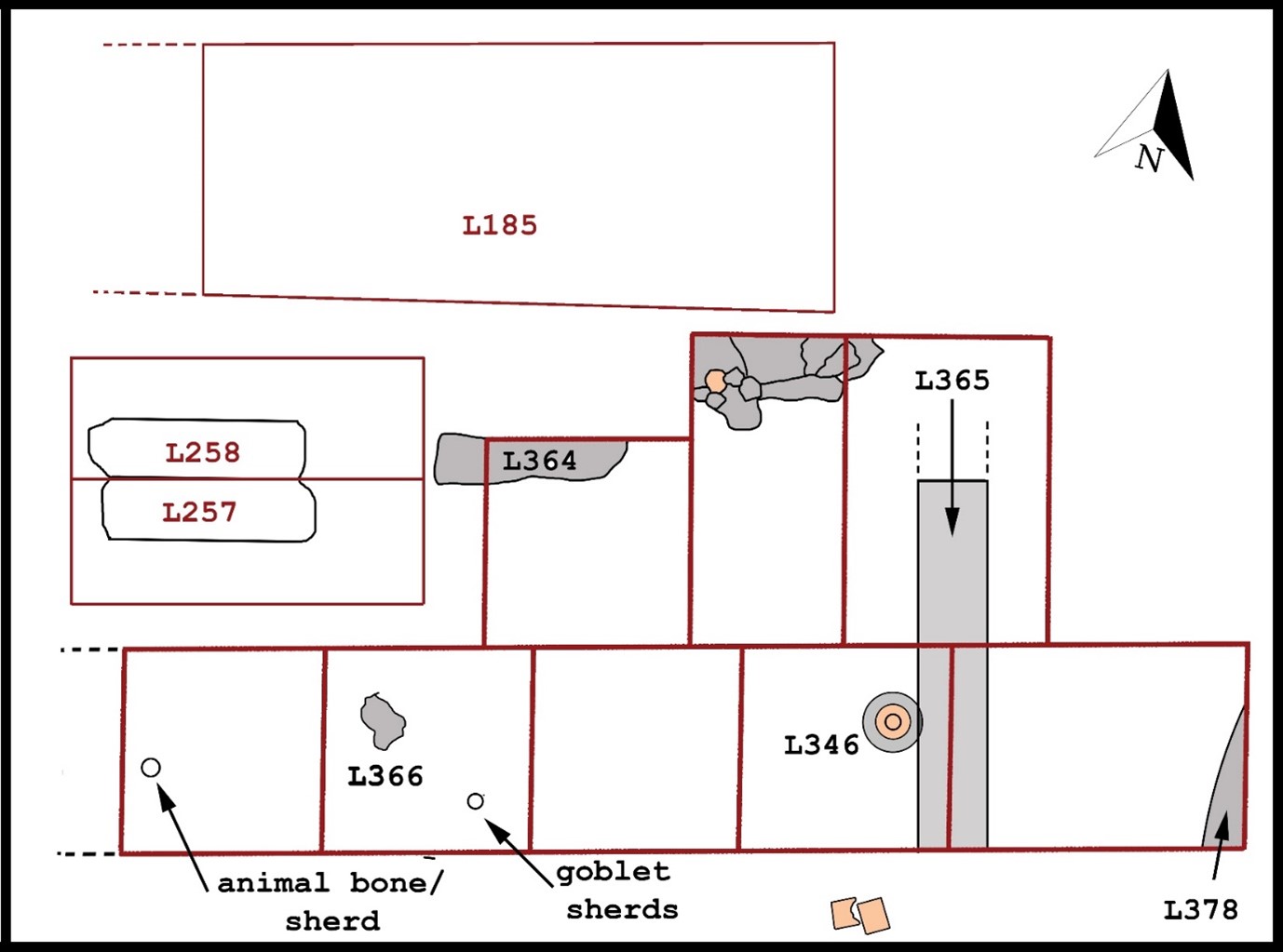

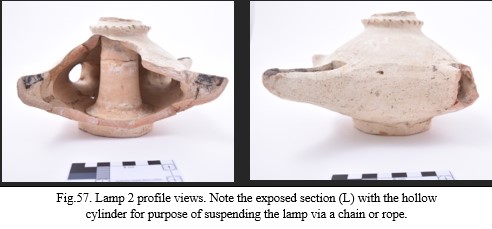

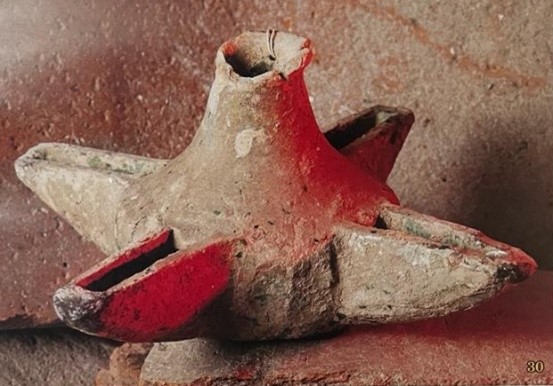

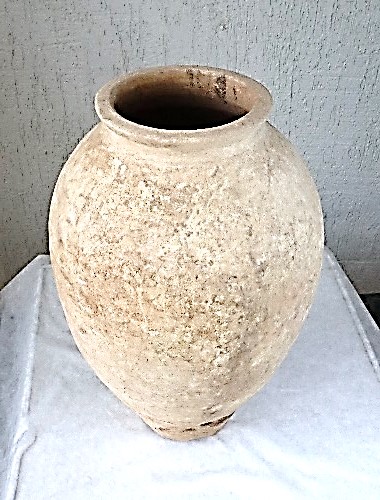

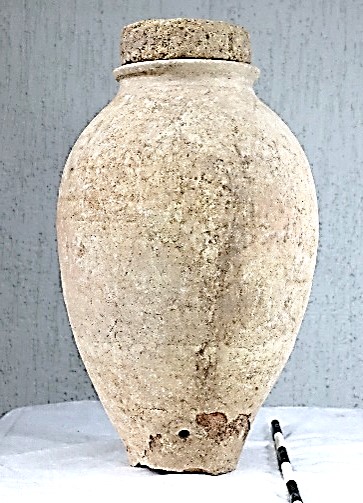

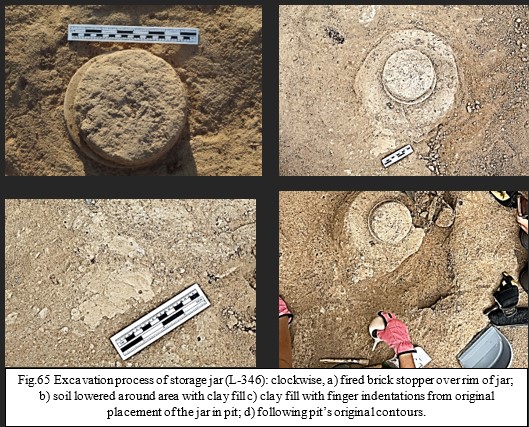

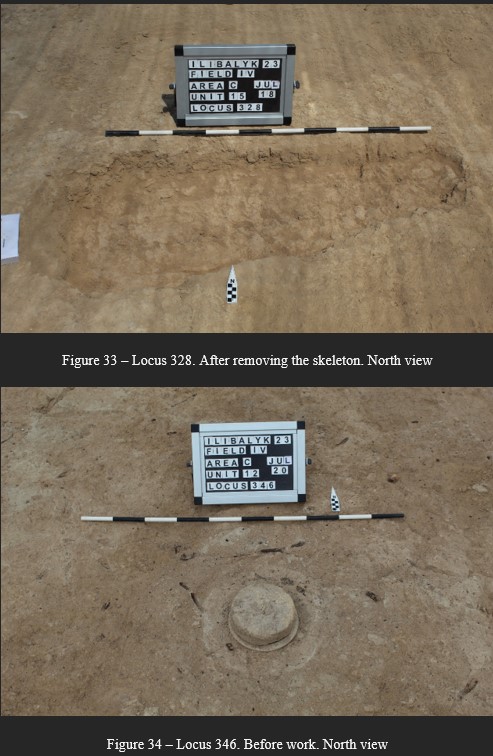

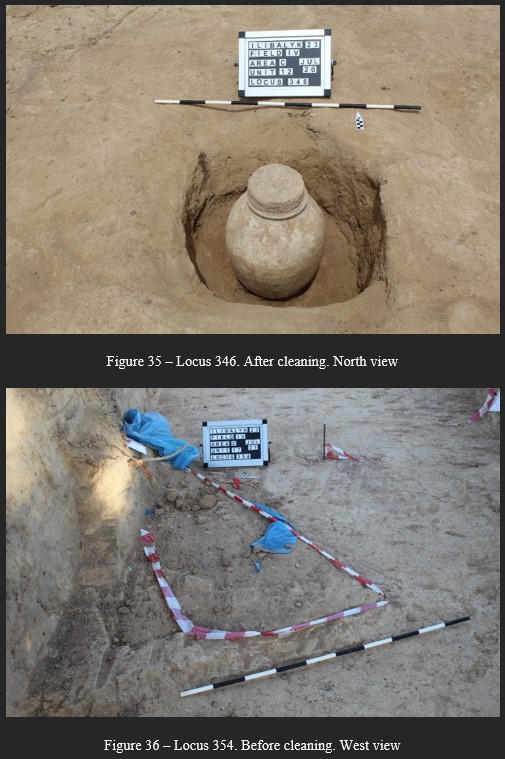

This section, designated L-185, contained a cluster of two small fruit trees hampering excavation efforts, was expanded to the south and west in 2020. This section lies between the cemetery of Area C and the funerary chapel. It also yielded additional pottery finds, including two 4-nozzel lamps (L-338), possibly used to light the martyrium. South of this section and near what appeared to be a retaining wall and platform parallel to the altar area, a completely whole vessel (L-346, a medium-sized storage jar, known as a khumcha in Russian) with an intentionally rounded, secondarily used fired brick stopper was discovered which had been inlaid at the floor level, likely utilized for storage of food stuffs or drink.

The medieval occupational surface was discerned in this section and the area identified as L-185 had gray-colored soil (Munsell 10YR 7/2), likely because of trampled ash like that discovered within both the altar area (L-240) and the chapel nave (L-230). This same-colored soil has often been found within the mudbricks of many graves within the cemetery (See 2021 Field Report, pp. 97-98). The area with the gray-colored soil appears to be contained within the possible enclosure of the currently interpreted martyrium and was possibly an enclosed structure. Further excavation will be needed to see if this potential structure was a self-contained building or an annex to the chapel.

Examination of the chapel on the east side of Unit 12 discerned a second wall (L-361), thought to possibly be a retaining wall that formed a semi-circular enclosure around the altar. Thus, the team decided to expand excavations to the east within the previously exposed boundaries. This area was contained within the initial boundaries of the previous excavation and was more definitely demarcated as a 5 EW x 16.5 m (82.5 m2) unit. Since this area was contained in the previously designated Unit 12, no additional identification was given. The purpose was to determine if any other features, cultural material and/or graves might be present. While clusters of pottery (including archaeologically whole vessels) and ash pits were discovered, no graves were discerned. (Appendix “Drawings”. Fig. 5).

The eastern, southern, and northern sides of U-12 is adjacent to the usual collection of trees as throughout Field IV, in which dense tall herbaceous vegetation, colloquially called wormwood (Artemizia) grows, along with low-growing shrubs and trees of the Laeagnus commutata variety (silver oleagenin). Additionally, wild apricot trees related to the common apricot (Prunus armeniaca Lin., Armeniaca vulgaris Lam) can be found. The soil in this eastern sector of U-12 is similar in type, color, and description as throughout the excavation site. The initial level for this northern sector of U-12, which marked the soil below the cleared surface first revealed in 2020, was designated as Locus 334 and is described below.

In total, 35 new loci were identified, and 3 previous loci were investigated, comprised of test pits in the northern sections, ash pits, pottery features, and two graves, one which was excavated (L-258).

Fig. 18. Loci excavated (and or investigated) in Unit 12, supervised by C.A. Stewart in 2023, in relation to previous season(s). Measurements and orientation are approximate. L-333 incorporates all the sub-divided test pits and the is designated level between the surface at excavation and the identified medieval occupational surface.

Fig. 19. Top plan of Loci excavated (and or investigated) in Unit 12, supervised by C.A. Stewart in 2023. Measurements and orientation are approximate.

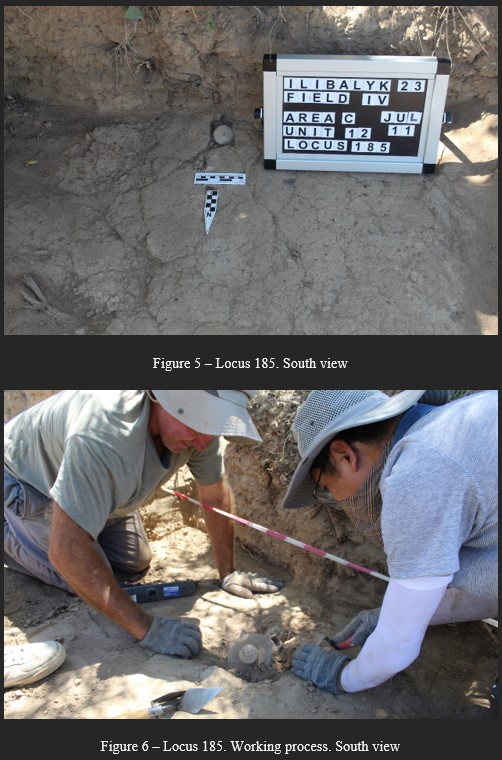

Locus 185

Level

(Appendix “Photos”. Fig. 5-7)

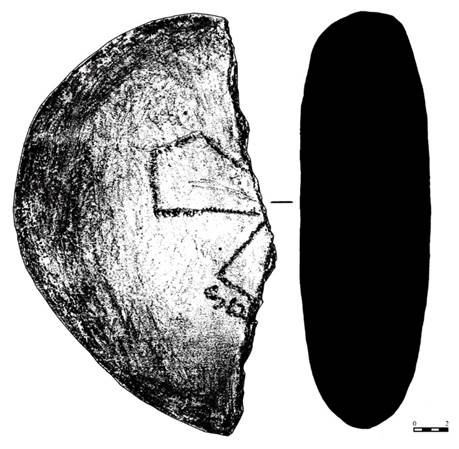

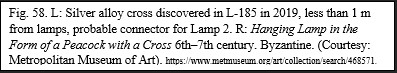

This locus, initially demarcated in 2019, lay on the south side of the cemetery at the south baulk of Unit 9C, identified as “ashy-colored soil” (2019 Field Report, p. 111). It was also in 2019 within the soil matrix of this baulk that a 5 x 5 cm copper cross in the cross patee (equilateral) style was discovered (depth 597.384 m. asl.; Ib_19_C_IV_001_I025; 2019 Field Report, pp. 7, 228). Two of the opposing crossbars contained pierce holes on each end. The Initial interpretation was that this cross might have been possibly nailed to coffin or hammered to a wall as a decorative piece. This interpretation was further bolstered when a kayrak (gravestone) (20.6 x 17.7 cm) with a simple cross inscription was discovered the following year (2020 Field Report, p 52, Ib_20_С_IV_I234), yet at a higher depth than the metal cross (597.703 m. asl.) by 31 cm. This kayrak was discovered about a meter away from the cross’ findspot.

In 2020, with the discovery of the funerary chapel in Unit 12, due south of L-185, the archaeology team began trying to discern the relationship between L-185 and the chapel itself, particularly because of the gray soil which continued to be revealed as more upper soil began to be removed. What was first thought to possibly be the typical, gray-colored mudbrick which has covered many of the graves in the cemetery, was now apparently some type of floor surface. (2020 Field Report, pp. 13-14). The dense, gray-colored surface contains many flecks of charcoal, which initially led excavators to conclude that the surface was exposed to burning, and possibly part of an open-air courtyard. The excavation, complicated by a cluster of fruit trees, continued to reveal this floor to the west. Yet, by the conclusion of the 2020 excavation, no connection with the chapel had been determined.

As part of the 2023 excavation goals, understanding the northern territory that incorporated the chapel was priority. Thus, excavators sought to fully reveal the gray-colored surface. Eventually, it was determined that this surface was compacted (possibly due to human traffic) with the interspersed charcoal fragments a part of ash that had possibly been intentionally deposited on the floor’s surface, as opposed to being an ash layer from a catastrophic fire, however, this latter hypothesis cannot be fully ruled out.

Initial level measurements were taken with the total station: SW: 597.321; NW: 597.342; NE: 597.371; SE: 597.561 m. asl. The modern surface level with the cluster of fruit trees was also measured: 597.970 m. asl.

After excavation commenced, in the northern area of L-185 [Block 1], an unglazed lamp nozzle was found along with a brick fragment, this appeared in situ as it was found under the geotextile. This find was in the soil fill near the two trees which, as mentioned, was also the location of several previous finds, including a kayrak (L-234) discovered in 2020 and a metal cross (Ib_19_C_IV_001_I025) found in 2019. While clearing new soil in and around the area of these trees, additional pottery was discovered, including what appeared to be a large, rounded knob connected to a vessel. This piece was left in place as it extended lower than the currently cleared surface. Photos were taken and an initial total station level was taken: 597.400 m. asl.

More pottery fragments were discovered in this northern section of L-185, including 3 blue glazed pieces that were possible fragments from an archaeological whole vessel discovered near the same spot in 2020 (Ib_20_С_IV_ 185_I002). Due south of these two pieces were 2 parallel fired bricks which appeared in situ. In addition, light gray soil was found under and surrounding these bricks with a boundary or edge running in an east to west direction. Tree obstruction continued to hinder this investigation. While initially thinking the edge demarked a grave, it became clear that these bricks are more likely in conjunction with a wall line extending from the chapel or part of the later identified martyrium.

While continuing to peel back soil around trees to discern possible feature(s) under trees and around the 2 fired bricks on the northeast side an attempt was made to discern the function of fired bricks. What initially was thought to be mudbrick with a burial chamber was hardened soil. The soil was lowered on both sides of the bricks so they would be on the same level with both sides of the bricks. More large pieces of charcoal were found west of the bricks.

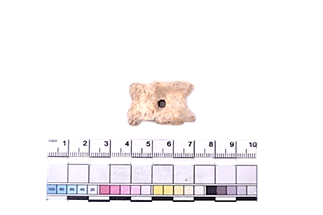

The soil area between the two trees was lowered. No cultural material was found in the first 30 cmbs, but, then at approximately 40 cm above the cleared surface, 2 other fired bricks were revealed, these lying horizontally. These bricks were at a slightly higher level than the other bricks on the northeast side of L-185. The first brick measured at a level of 597.615 m. asl. and the second brick to the south measured 597.575 m. asl. and they were separated by approximately 30 cm. The soil fill between the trees was then lowered to match the level of nearby L-333 and a few pottery sherds found, including a small piece of green glaze ware. Also discovered was a small piece (get dimensions) of worked bone possibly calcined by fire and part of a possible utensil, yet this is uncertain.

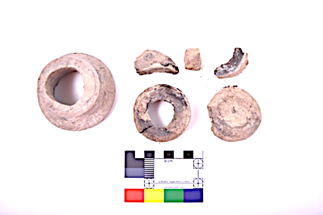

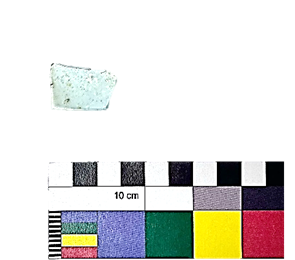

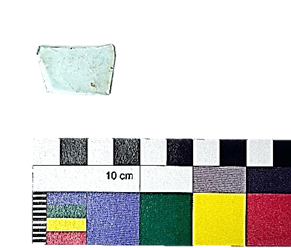

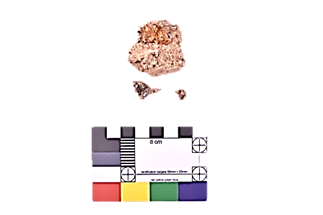

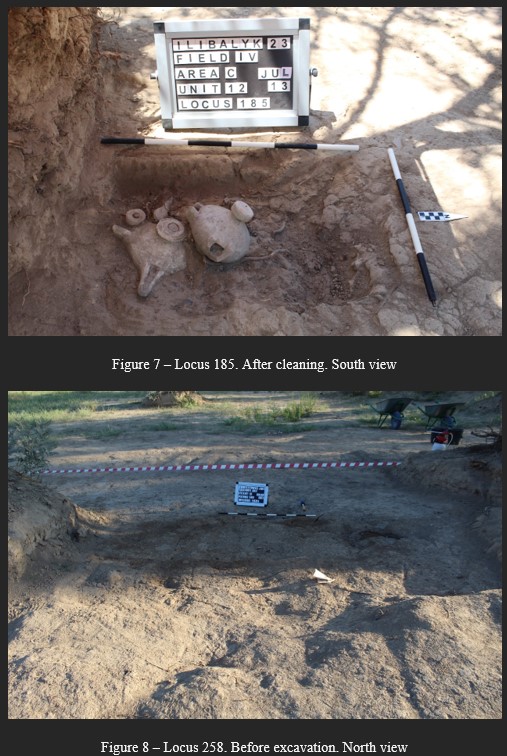

As excavations continued, focus was turned to the ceramic feature which initially revealed a four-nozzle lamp, virtually complete, yet with two revealed nozzles broken at the intersection with the vessel’s body. Immediately south of this vessel, another round decorative pottery fragment was discovered, thought to be a broken fragment of the first vessel. However, when proceeding to remove the 4-nozzled lamp, a second lamp also with four nozzles, yet with a variation in style, was discovered next to the original find. Both vessels lay at a slight angle parallel with each other, with the first partially on top of the second. Due north of these vessels, large wood fragments was also discovered, which appeared to be either from a large root, but more likely, wood flooring or even fragments from a box or chest, yet no complete determination could be made. A new locus was assigned to this pottery feature, Locus 338.

The soil in and around the 2 lamps was then cleared to reveal the occupational surface more clearly, and it appeared that the lamps may have been buried slightly lower than the occupational surface, or perhaps inside a container, yet no wood that might have been found from the floor of a container was discerned. To the west of the lamps, yet another pottery feature was discovered. This appeared to be a round slightly hollowed cylindrical piece, which eventually was identified as a base to a vessel It was assigned a locus number, L-339 (see locus description). Both features were measured with the total station: L-338 Lamps, Level 597.285 m. asl. L-339 Cylindrical pottery piece 597.291 m. asl. Thus, these pieces were likely deposited in this area, possibly deliberately, and at the same time.

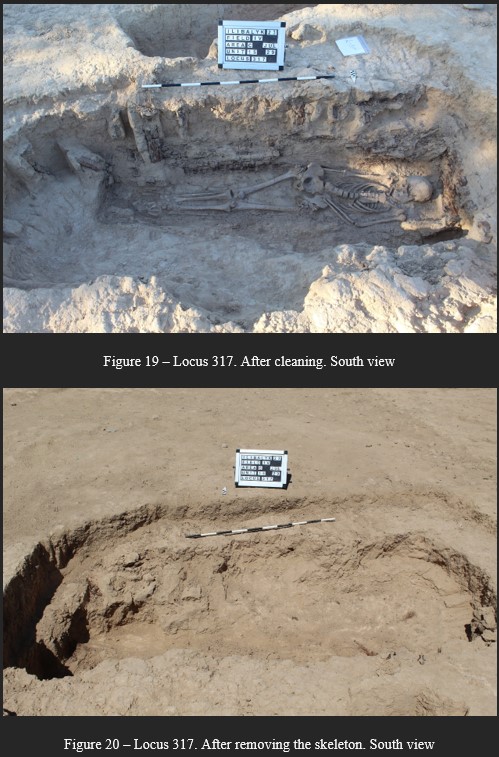

Wood continued to be found on the gray-colored occupational surface and an attempt was made to trace it both to the east and west immediately north of the section with these pottery features. This area lay on the borders between U-12 and U-9C. Possible mudbrick was observed with this wood and what appeared to be border lines on both the north and south of the wood feature. Excavators initially thought it marked a grave with a wood cover (such as previous discoveries in the cemetery, L-146, L-291, and L-317), yet uncertainty remained as to whether the wood was natural roots from the obstructing trees, or if it was some type of flooring. Most certainly contemporary roots were seen on this level, however, they appeared to be tracing along the possibly wood planks. The ceramic features (L338/339) were kept in situ for a longer period in hopes of determining the full context. This wood feature was given a locus (L-340) with a total station level taken: 597.294 m. asl.

As excavations continued, in the northeast corner of the revealed, gray-colored surface an area of burning (calcined, red soil) was found along with an ash spot. The wood fragments proceeded across the entire area, and it was determined that the pottery vessels were probably sitting on top of the wood, which were planks of about a 1 cm wide to 1.5 cm thick, though it remained difficult to discern. Final clearing with a mechanical blower revealed a line of 5 single course mudbricks, to the east of the pottery feature by approximately 1 m and extended 1 m long proceeding in an approximate north-south direction immediately parallel with the gray-colored surface. The bricks were not in a perfectly perpendicular straight line but appeared to extended north/northwest along the edge of the gray surface. A possible hypothesis is that this section of L-185 was possibly part of a foundation for a wood structure or floor that stored vessels or the line which appears to be in line with the whole khumcha pottery feature, L-346. This area of L-185 currently does not appear to contain a grave, though the final determination is still not made due to the obstruction of the trees.

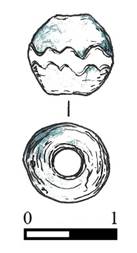

Once the context of the east side of L-185 was better determined, the lamps (L-338/L-339) were removed and carefully packed for later investigation and cleaning in the field lab. Both lamps had 4 nozzles, yet not all of them were intact or had survived unbroken. The feature in L-339 was the base to a chalice which was later confirmed in the field lab and matched with another fragment to this based that was discovered in L-341. Soil and wood samples were bagged for later analysis.

L-185 was then extended to the west for the purpose of tracing the gray-colored, compacted soil floor. It was extended to the west by 10.6 m and to the north by 2.4 m. As the tracing continued, a “turn” to the south at approximately 3 m to the west of the gray-colored flooring was detected which extended to the south just beyond the western side of the grave boundary discovered in L-258. This means that this grave and the probable grave immediately parallel (L-257) were contained within a structure, some form of mausoleum or martyrium in conjunction with the chapel. The 20-cm thick, compacted gray layer with ash and large flecks of charcoal may be indicative of the ceremonial use of ash in Syriac funerary practice (Wiśniewski 2018, 168; Wickes 2015, 120; Brock 2009, 180).

Also, in the northern extension, on the northwest side of the gray-colored flooring, a soil change was detected, containing loose sandy loam with small pebble-sized gravel and soil with a yellowish tint and no charcoal inclusions. It extended 100 cm east-west and could have served as a possible north entrance from the martyrium to the cemetery. Regardless of its function, it was outside the boundary of the gray-colored floor.

Since the soil around the tree could not be completely removed, a profile was created by the excavators to possibly detect features within an “unexpected” south baulk (230 cm) and a smaller east baulk (80 cm). This profile was then drawn (described below). The south baulk profile revealed at least 3 clusters of mudbricks, which may indicate detrital collapse or some other feature, such as grave(s). The level of the compacted, gray-colored floor was also clear within the profile and was approximately 12-20 cm thick with the bricks extending below and into the surface. This indicates possible phasing and with the usage of the structure under investigation over a long period. It also suggests that the lamps were deposited in a hole in the floor later, which might indicate rapid flight with the hope of eventual return, or some sort of ceremonial destruction of what would be considered sacred vessels by the community.

Stratigraphy Profile Description (L-185)

An east-to-west line of three fruit tree clusters in the central section of L-185 were kept in place to adhere with state regulations within the protected land area in which Areas A, B, and C of the cemetery excavations have occurred. The two tree clusters on the far eastern side of L-185, which stand east of the probable grave (L-257) and the excavated grave, (L-258) impeded the team’s ability of fully interpret the supposed martyrium that resides north of the funerary chapel. During this season, excavators sought to remove soil as closely as possible around these trees without creating permanent damage. In addition, an 80 cm stretch of soil to the west of the easternmost tree was shaved closely to create a baulk face in which to read the stratigraphy. The same was done with the soil of the other tree to the west, this time on the north side of the tree, creating a south baulk face extending 230 cm from east-to-west. The following descriptions detail the features as recorded within the profiles of these two baulks.

East baulk profile

This profile of the 80 cm east baulk of L-185 (within U-12) was characterized by three layers: an intermixed layer of topsoil from the plow zone and current excavation work, a layer of sandy silt, and a light brownish gray layer of compacted floor.

1. An intermixed layer of topsoil from the plow zone and current excavation work. This first layer of the profile was comprised of a light gray (Munsell: 10YR 7/2) sandy silty loam ranging 40 cm deep on the north side to 45 cm on the east side of the profile This layer extended across the 80 cm length of the profile and completely covered the sandy silt layer that lay under it. The soil was intermixed with soil from both the Soviet-era plow zone and the backfill from previous excavation work that was first initiated in Area C in 2017. The soil had inclusions of root systems and from churned up humus. No cultural material was visible in the soil.

2. A layer of sandy silt. This second layer of the profile was comprised of a pale brown sandy silt (Munsell: 10YR 7/2) with the top of the layer ranging from 40 cm on the north side below the surface and descending to 47 cm on the south side below the surface. The layer’s width ranged from 15 cm on the north side and descended southward to a width of 7 cm. The base of this layer overlapped the lower gray layer of compacted flooring and extended evenly across the entire profile. The layer had root disturbance and root systems with no other inclusions.

3. A light brownish gray layer of compacted floor. This third layer of the profile was comprised of a compacted light brownish gray soil (Munsell 10YR 6/2) with multiple pieces of black charcoal inclusions. The top layer appeared 55 cm below the surface and extended evenly across the entire length of the profile. It was 30 cm wide. This layer is interpreted as the floor to the martyrium. No mudbricks were seen within this layer.

South baulk profile

This profile of the 230 cm south baulk of L-185 (within U-12) was characterized by three layers and 1 feature: an intermixed layer of topsoil from the plow zone and current excavation work; a layer of sandy silt; a light brownish gray layer of compacted floor; and three mudbrick clusters within the compacted floor.

1. An intermixed layer of topsoil from the plow zone and current excavation work. This first layer extended from the 85 cm demarcation rather than across the entire baulk since the top two layers on the east side of the baulk had been removed due to excavation. This layer was comprised of a light gray (Munsell: 10YR 7/2) soil which was a mixture of Soviet-era topsoil and backfill from previous excavations that began in 2017. It contained much churned humus and root inclusions. Its length, from the 85 cm mark, was 145 cm and its width ranged from 27 cm on the east side 7 cm on the west of the profile. It overlapped across the entirety of the sandy silt layer. Inclusions of red clay pottery were visible within the cross section.

2. A layer of sandy silt. This second layer extended from the 85 cm demarcation rather than across the entire baulk since the top two layers on the east side had been removed due to excavation. This layer was comprised of and very pale brown (Munsell: 10YR 8/3) sandy silt. It contained inclusions from the tree root systems as well as cultural material such as red clay potsherds and possible fired brick fragments. Its length, from the 85 cm mark, was 145 cm, with an undulating width ranging from 17 in the central section of the layer to as narrow as 4 cm at the 190 cm mark on the west side. Its depth below the topsoil ranged from 27 cm on the east side to 7 cm on the west side. It is possible that the undulating nature of this layer is due to the presence of mudbrick which this layer may have eventually covered. These bricks may be from possible graves which were a part of the martyrium, though this is speculative.

3. A light brownish gray layer of compacted floor. This third layer of the profile was comprised of a compacted light brownish gray soil (Munsell 10YR 6/2) with multiple pieces of black charcoal inclusions. This layer’s length extended across the entire 230 cm of the profile. On the east side, this floor had been exposed from excavation. The upper two layers then covered the flooring starting at the 85 cm mark. The floor began to ascend slightly at the 100 cm mark, reaching its peak at the 190 cm mark, being 10 cm higher and then descending again by 10 cm on the west side of the profile. The black charcoal inclusions, some up to 7 cm wide, were interspersed throughout the layer. The soil was hard and compacted, yet some roots from the tree appear to have penetrated the layer on the west side of the profile. Three clusters of mudbrick, some gray, some with a reddish-brown tint, were also visible within this floor layer.

4. Three mudbrick clusters within the compacted floor. This feature within the third layer of the profile manifests itself as three clusters of mudbricks. The first cluster began at the 18 cm mark with a large amorphous mudbrick (approximately 30 x 10 cm) of reddish-brown tint quite visible within the compacted floor of the third layer. Additionally in this first brick cluster were three bricks with this same color (approximately 23 x 7 cm) in a straight line 10 cm higher in the profile beginning at the 23 cm mark and proceeding eastward and terminating at the 75 cm mark. The second cluster of bricks began at the 100 cm mark with three mudbricks in a perpendicular line from the base of the baulk. The bottom brick was reddish-brown (15 x 7 cm) with an amorphously shaped gray mudbrick immediately on top of the bottom brick. This gray brick measured 15 x 7 cm. A third gray mudbrick appeared to have been placed on top of the second brick in a perpendicular position (15 x 7 cm) with a smaller fourth brick (10 x 5 cm) adjacent to the west and perpendicular (90 degrees) to the west of this third brick terminating at the 120 cm mark. The third cluster of bricks were comprised of four mudbricks of various sizes in a straight line across the base of the profile beginning at the 140 cm mark and extending to the 213 cm mark. The first brick was gray and measured 20 x 10 cm, the second brick—due east with the east end slightly below the bottom boundary of the baulk—was reddish-brown and appeared broken with significant detritus. The third and fourth mudbricks (which may be part of one brick) were gray with reddish-brown inclusions, measured approximately 10 x 5 in the baulk. It is possible that the bricks in the second and third clusters are part of the same feature, likely a grave.

Locus 257

Probable grave

This locus, as well as L-258, were first revealed and identified during the 2020 excavations and described as being a “feature of bricks and loam.” (See 2020 Field Report, p. 27-28). In L-257, the soil was described (and remains) as a “light brown loam” almost reddish, in contrast to the gray colored soil and faintly discerned bricks for L-258. Even at the early stage of excavations of 2020 which revealed the funerary chapel, the team was intrigued by these two large rectangular features and speculated that both loci, based on their size and east-west orientation, might be graves, and even speculated it might be included as part of a mausoleum. Yet, the trees, planted within the past 2-3 decades, have consistently hampered access and the ability to interpret this section archaeologically.

The following season (2021), the excavation objectives included further investigation of both L-257 and L-258 attempting to confirm whether these features were graves (2021 Field Report, p. 7). Despite troweling these loci and lowering the soil by 10-15 cm, the conclusion was that these loci were not graves, but instead marked a delineation between the cemetery to the north and the funerary chapel’s territory. It was even speculated that it could have been part of a gate construction and/or entryway into the cemetery itself in which the deceased was escorted from the chapel to the grave. (2021 Field Report, p. 96). However, following this season’s removal of geotextile from both these loci followed by mechanical blowing, the mudbrick covering these graves, particularly that of L-258, became obvious that these two features were large, adult-sized graves.

Locus 257, which lay immediately south and parallel with L-258, as first identified in 2020 measured 210 (E/W) x 80 (N/S) cm. Interestingly, its soil had more of a reddish-brown hue, than that of L-258, which had the more characteristic, gray-colored soil found in many of the cemetery’s graves. In fact, due to this difference, and because the gray-colored bricks of L-258 were more easily discerned, it was decided to excavate L-257 after its neighboring locus to the north. Lack of time and the rather deep grave pit from L-258, prohibited excavation of this locus. Yet, on current interpretation is that this is a probable grave, placed immediately next to L-258. If this is true, it is the first example of two graves being placed adjacent one another and more will be said of this in the Grave Excavation Findings section. The other possible interpretation is that this is part of a wall that separates the martyrium from the chapel. Only further excavations will answer this question.

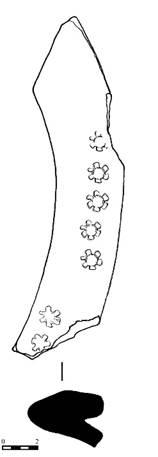

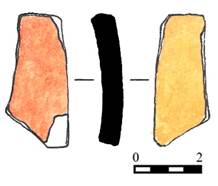

When this feature was first revealed it measured at a level of 597.364 m. asl. Since excavations concentrated on the other grave to the north, no further measurements were taken. This locus’ importance is obvious given its location which is now interpreted to be within the martyrium due north of the chapel and part of a possible double-grave in conjunction with L-258, whose excavations are detailed below. During sweeping of the soil in this section, a large pottery fragment with a decorative feature was discovered (Ib_23_C_IV_258_I001).

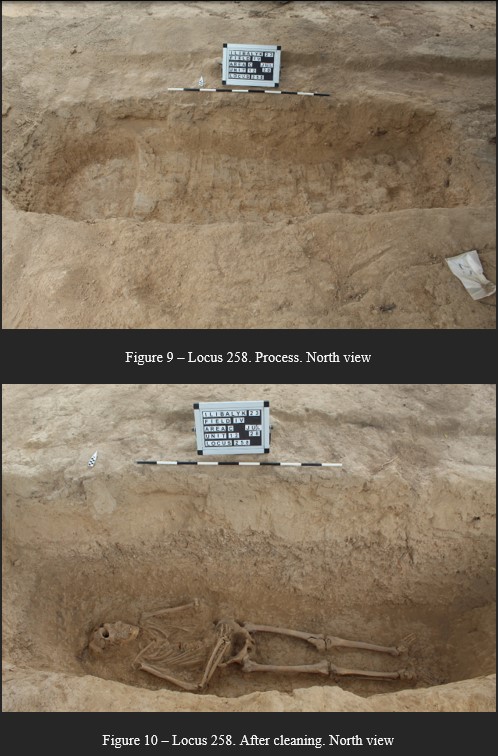

Locus 258

Grave

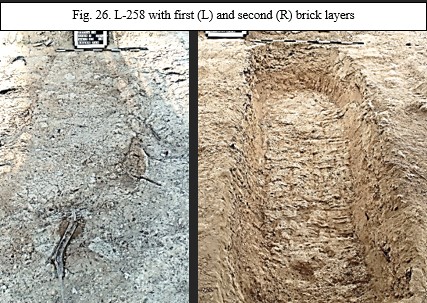

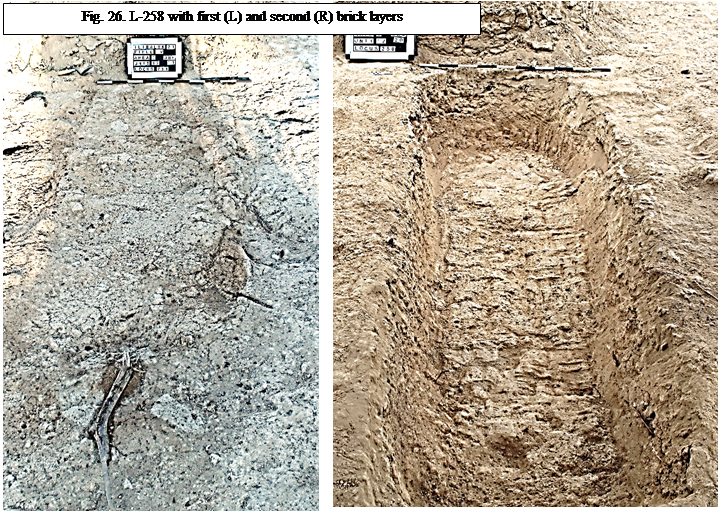

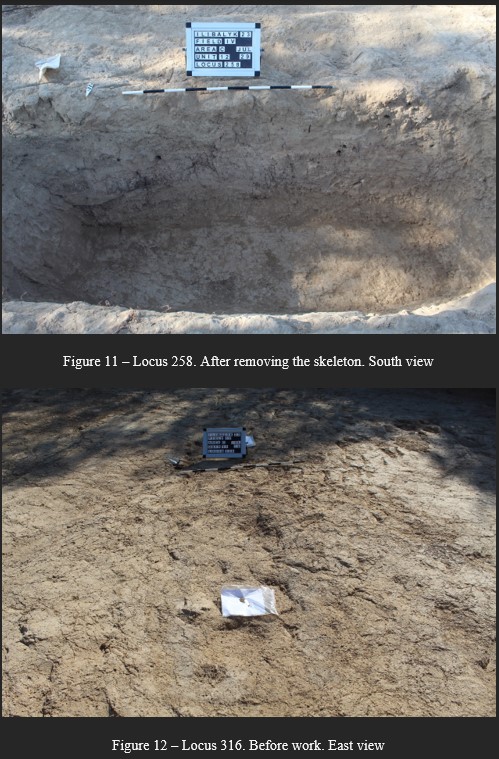

(Appendix “Photos”. Fig. 8-11, “Drawings”. Fig. 6)

As mentioned above (see L-257 description), this locus was initially identified in 2020 with lack of clarity as to whether this feature was a grave. Further investigation in 2021 caused excavators to think this rectangular feature, originally measured at 230 (E/W) x 70 (N/S) cm, was not a grave, but rather a possible entryway or foundations to a gateway that separated the funerary chapel from the cemetery in Area C. However, following routine removal of the geotextile that had been placed over this section of U-12, the gray-colored mudbricks, first discerned in 2020, had become more distinct and in a usual pattern with the bricks extending perpendicularly, or north-south, across the grave. This became even more clear following mechanical blowing of the soil.

This locus was located due north of L-257, an almost identical feature in dimension and laying adjacent to L-258. The soil, likely due to the detrital melt of the bricks, had a gray-colored hue. Some of the bricks were not placed in a uniform manner, particularly on the east side of the grave and the upper part of the chamber may have been lined, at least on the east and west sides with brick. This appeared to be similar to what the team has classified as burial Type 2B, or a vertical mudbrick-covered pit, yet later it was seen to be a variation to this type, and given a new classification, Type 2F, which is a newly assigned type based on this double brick layer variation.

Once this locus and L-257 were cleared of loose soil using the mechanical blower, it was obvious that these features were two adult-sized graves parallel and adjacent with one another. Because the mudbricks appeared more distinctly in the soil of L-258, it was determined to excavate this grave first as opposed to L-257. Once the initial boundaries were established, photographs and altitude levels were taken: SW: 597.334; NW: 597.308; NE: 597.345; SE: 597.313 C: 597.298 m. asl.

As excavations began, a 250 x 300 cm square was cleared around both loci (L-257/L-258) and opening photographs were taken. The southeast corner of L-257 was levelled to assist with access to L-258 because that section of the revealed soil was higher than the rest of the arbitrary square. The boundaries to the north, south, and east were traced. The soil which surrounded a tree lay immediately west of the grave and extended up to the modern surface making access to the west end of the grave problematic. However, the grave’s western boundary ended just prior to the tree obstruction, so the soil surrounding the tree was left in place. Mudbrick detrital melt was on the east side the grave, but the foot (east side) of the grave was discernable just west of the melt. A few small potsherds and animal bones fragments were found in this upper fill.

Once the outer parts of these two loci were leveled, excavators began to steadily remove the grave fill for L-258, beginning on the west side of the grave. It was then determined that the grave extended beyond the 300 cm designation to the west by 19 cm, with an approximate dimension of the chamber from the upper part of the cleared surface, measuring 238 E/W x 95 N/S cm. Following this initial removal of soil within the grave’s boundaries near the upper surface of the grave, a well-defined was revealed. More mudbrick was noticed continuing along the grave’s west border and along the south side. These mudbricks appeared to have been laid perpendicular, or in a north/south direction, across the width of the grave. Following mechanical clearing of the soil, photos were taken along with a LIDAR scan utilizing the iPad Pro. Finds included pieces of a fired brick or possible tile/wall fragment was discovered, a possible corner piece with pre-fired incision which lined the outer edge of this brick/tile.

Following three passes with a large pick through the medium-brown soil, the soil of the grave fill transitioned from a sandy loam to clay and a second layer of hard, dark grey-brown mudbrick was found. These bricks first appeared about 32 cm from the western most point of the grave’s boundary and about 33 cm below the revealed surface. Bricks on the east side followed the curvature of the grave. Photos were then taken of this second layer once the clay soil was removed. Such a discovery is a first in the cemetery at Ilibalyk, as a double-layer of mudbricks has never been discovered which may indicate a grave of higher status or level of importance. All soil was carefully sifted with the discovery of animal bone fragments and very small number of common ware potsherds.

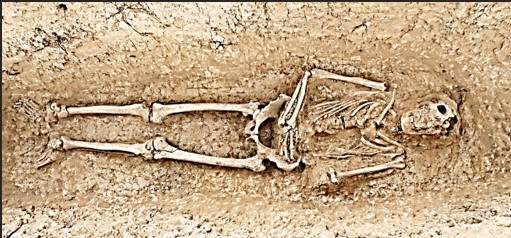

The second mudbrick layer was carefully traced and photographed prior to removal. It measured as an elevation of 596.942 m. asl. The soil just under this layer was soft and medium brown in color. At this point, two human adult-sized metacarpal bones (MC 3/MC 4) were revealed on the west side of the grave. Initially it was thought that these hand bones from an adult-sized left hand might be immediately next to the face of the skull. Regardless, it was clear that the western boundary still needed to be extended westward. The metacarpals were measured with the total station (596.811 m. asl.) and then covered with geotextile. The soil on this side was lowered to the same level. However, at this point, no skull was found. The soil in this western most area was tan with reddish and brown clay. East of the metacarpal bones, the soil remained the soft, medium brown fill which contained flecks of charcoal. Also, at this level in the gave was the so-called detrital layer (found in two layers throughout Field IV at these levels), with the typical white calcite-type particles.

Eventually, to the east of the revealed metacarpal bones, a human tooth and then the cranial skeleton was found (July 21, 8:15 am) at a level of 596.716 m. asl.— 10 cm below the left hand, which raised the first question as to the placement of the left hand, resting at an unusually higher level than if the hand were placed on the thoracic region, which would be approximately 20 cm below the hand. More soil was carefully removed from around the face and cranium. Interestingly, the skull contained no soil fill, as is typical. The bones of the cranium, particularly the facial bones, appeared brittle with much taphonomic damage, particularly to the frontal lobes and right orbit. The skull was not raised at time of burial with the gaze skyward. Initial examination showed that maxilla and upper front incisors were quite worn. Clearing of the soil just north of the skull revealed another possible mudbrick or hardened soil. A small pottery fragment was also found in the soil fill between the maxilla and mandible. At this juncture, photographs and another LIDAR scan was taken.

During detailed clearing of soil around the skull, excavations on the east side of the grave commenced attempting to locate the lower appendicular skeleton. The left patella was found, followed by the left femur. The patella was damaged slightly due to rodent activity (gnawing). The right femur was revealed next; however, it was then apparent that this bone extended into the south baulk of the grave, meaning that the right lateral side of the body would not be fully exposed without extending the soil removal to the south. The entire grave, including the revealed sections of the skeleton were covered with geotextile and then the grave’s fill was extended by 5-7 cm. By this extension, it was confirmed that very little barrier exists between the two graves (L-258/L-257), further investigation will be necessary to determine if a narrow wall existed between these graves or not.

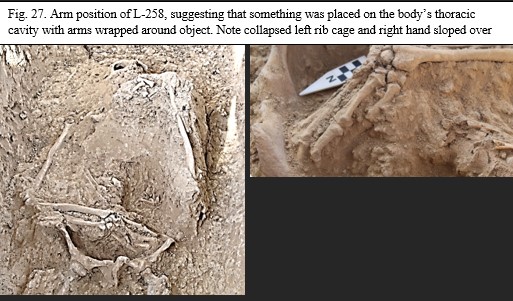

As excavations continued, the body’s left arm, specifically the ulna and radius extended upward along a slope at approximately a 20-degree angle with the left hand resting on soil that extended 20 cm above the skeleton. Soil was cleared around this area just above the suspected thoracic cavity with no success in determining the presence of an object under the hand, even though the intermediate and proximal bones of the third and fourth finger appeared to follow the curvature of the soil, as if something was grasped by the interred person. The left wrist was also flat, thus, whatever the interred was holding was large enough to rest the entire wrist and hand on the object. No organic material or soil color change was noticeable with the remains or extended under the soil onto the thoracic cavity. The right radius and ulna were revealed as placed at a 90-degree angle across the lower abdomen, some 12 cm from the right ilium. This right hand was at a lower elevation than the left hand, yet the right and left hand were parallel as though something large lay across the left thoracic cavity with the hands placed on an object as if grasping it. This hypothesis is further confirmed by observing the right hand as above the pelvis by 7 cm (596.614 m. asl.) and not resting or intermingled with the thoracic vertebrae. This right hand also seemed to have been laid over something as if grasping it, as the right metacarpals and phalanges lay as over a rounded object. Thus, the right hand also was on top of the object included within the grave. Eventually, excavations revealed that the entire left thoracic cavity had at some time following burial collapsed under the weight of the object placed in the person’s arms at interment. Since no material was detected, it is best to assume that the object was organic, leaving no visible traces as to the object’s identity. No grave goods were discovered within the tomb, nor were they detected in the sift.

Another mudbrick fragment was discovered along the south side of the grave and aligned with the body’s left hand, yet, at a lower elevation. Mudbrick or mudbrick detrital melt lined the base of the mandible. Photographs were again taken which concentrated on the arms as placed on top of the suspected object. An extremely hard, dark brown elastic soil continued along the north side of the grave. This was apparently the packed earth, known in Central Asian contexts, as paksa.

As excavations continued to reveal the skeletal remains, the cranial bones were inadvertently damaged further due to lack of impacted soil in the skull. The skull’s left orbit and frontal bone completely collapsed. The arms were left in place with the soil under the hands for photographs, after which the left radius and ulna were removed along with the soil under the left hand which was bagged for analysis to hopefully determine what was placed on the torso with the hands lain on top of the object.

The mudbrick fragment to the north of the skull was removed and a second piece attached to it was revealed. This brick appeared to continue westward under the soil which lay beneath the left hand. This mudbrick or mudbrick melt that continued around the base of the mandible and was detected inside right humerus, underneath the right ribs, around and beneath the right hand. This may have been put in place to help support whatever the deceased was holding. While the left ribs and thoracic cavity was completely collapsed with significant taphonomy, the right ribs were in good condition except for the lower posterior ribs near the vertebrae, which were badly preserved. This is perhaps, also, a result of the weight of the potential objected.

Excavations continued with the exposure of the tibias and the right and left extremities. Further soil removal was completed, with the remains photographed and 3D photographs taken. Skeletal elevations were taken with the total station: Head: 596.693; Pelvis: 596.504

Feet: 596.542 m. asl. Teeth samples were taken for future aDNA and C-14 analysis. The skeletal remains were then removed, measured, labeled, and packed according to procedure and following a final clearing and sifting of the soil, final grave levels were taken: W: 596.563; C: 596.484; E: 596.540 m. asl. To date, this grave chamber is at the fifth lowest elevation of all those discovered at Ilibalyk.

Locus 333

Level

After removing the backfill using shovels and wheelbarrows and peeling away the geotextile from all of Unit 12, the entire unit, incorporating the chapel and its environs, was cleaned using hand brushes, dustpans, and a leaf blower as mentioned previously, the geotextile remarkably preserved the remains of the mudbrick chapel exactly as left in previous seasons since its discovery it in 2020.

Using the total station, an area to examine within Unit 12, designated Locus 333, was delineated. This rectangular locus measured 12 x 6 m and lay immediately north of the chapel and due south of L-185. The purpose was to investigate this space between the chapel and the cemetery since it was thought the medieval occupational surface had yet to be revealed and clarity was still needed in determining the boundary between the chapel and the cemetery. It is important to note that this locus included three small trees which lay between L-333 and L-185, which excavators worked around. The two trees were clustered together and within the locus designated as L-185 (see description above). These two loci were designated as Block 1 during the 2020 excavations. The plan involved lowering this section between the north chapel wall up to boundary of L-185 marked by the physical boundary of the aforementioned trees. Initially, the plan involved lowering this level by an additional 20-25 cm below the cleared surface. L-333 was measured out according to cardinal points and measured as 19(E/W) x 6 (N/S). It was then decided that the locus would be sub-divided in segmented 2 x 2 m or 2 x 3 m test trenches to provide a more controlled environment and reach the medieval period occupational surface, which incorporated loci L-336, L-337, L-341, L-342, L-344, L-347, L-359, and L-364 (Appendix “Drawings”. Fig. 6-15). No baulk was maintained between any of these trenches due to the shallow depth of 20-30 cmbs was all that was necessary. The entirety of L-333’s boundaries were incorporated a newly identified possible retaining wall (L-365) on the east, ending at an arbitrary location due south of the eastern edge of L-185. The southern boundary for L-333 was marked approximately 1 meter north of the chapel’s northern wall (L-239). L-333’s northern boundary extended to the line of trees (described above) and adjacent to L-185 on the eastern side of this locus, and on the western side to the graves (L-257, L-258) which appears to be part of a possible martyrium, although the southern wall for this architectural feature is yet to be discerned or may be connected to the chapel. Time limitations prohibited digging in the section immediately next to the chapel’s north wall which would be necessary to make that final determination.

The opening levels for this 19 x 6 m trench measured: SW: 597.432; NW: 597.295; NE: 597.489; SE: 597.539; C: 597.503 m. asl. Various other features, such as ash pits or gray soil, and an archaeological whole vessel will be described in the context of the sub-divisions.

Locus 334

Level

This locus designated the level on the far eastern side of U-12, beyond the funerary chapel (L-238, L-239) first identified during the 2020 excavations. This was based on the discovery of another, new wall (later labeled L-361) that appeared to run parallel with the far eastern wall of the chapel (L-239).

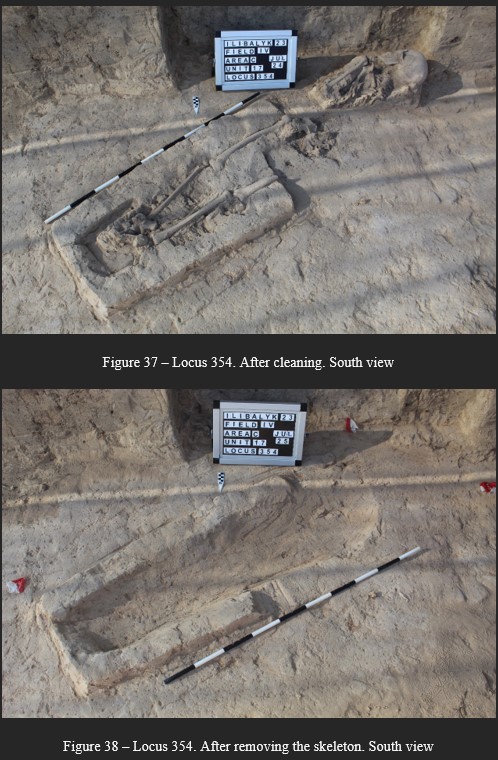

Following initial demarcation of the 5 x 16.5 m site which closely followed the previous excavation boundaries and following drone and ground photography, the section was cleared for new growth, the soil was scraped with shovels and then mechanically blown. During this process, several pottery sherds were uncovered including one sherd of blue glaze along with a few animal bones. During a visual inspection of the excavation area, eight features were identified, consisting of a layer of loose gray and dense brown loam from the upper excavated layer. Two dark, gray loamy sections were noted within the soil (L-343); a dense light brown loam in the eastern part of this locus was also noted, labeled L-363.