| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | Publications |

Starting point

The place of Urgut lies about 30 km to the south of Samarkand in former Sogdiana. Today it belongs to Uzbekistan. Near Urgut there is a rock face covered with around one hundred ca. 1000 years' old Syriac inscriptions and crosses. One of them is dated to the year “1206 of Alexander” which corresponds to AD 895.3 They may be linked to the Church of the East, also known as Nestorian Church.4 The Church of the East, whose see was located in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, as off 780 in Baghdad, Iraq, numbered during its heydays in the 12 th /13 th century 27 metropolitan sees, more than 200 bishoprics and ten to fifteen million followers. Its dioceses stretched from Egypt and Syria in the West to Mesopotamia, Iran and Central Asia till China, Mongolia and India in the East. Nestorian, respectively Eastern Syriac Christianity reached Sogdiana in the 5 th century; the bishopric of Samarkand was elevated to the rank of a metropolitan see by the 9 th century at the latest, probably earlier. Christianity vanished from Sogdiana towards the end of the 14 th century.

In 1916 a small bronze censer was found in Urgut dating from the 8 th /9 th century. It features scenes from the New Testament and is now kept at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. (Nr. CA 12 758).5 Towards the end of the 19 th century, two Nestorian tombstones featuring an engraved cross were found at or near Urgut, they are now at the Museum of Ashkhabad, Turkmenistan.6 Also from Urgut is a wearable cross made out of local coal shale. Additional finds from this part of Sogdiana dating from the 7 th to the 9 th century indicate a Christian community of that time. Among them there are coins dating from the 6 th to 8 th century found in Tashkent, Samarkand and Penjikent which feature on the reverse side a Maltese cross.

These latter finds are important, since only rulers or city governments would strike coins. An ostracon, a fragment of a vessel featuring several lines of the Psalms taken from the Peshitta Bible and written in the Syriac Estranghela script as well as a bronze cross also stem from Penjikent. In Samarkand, another cross and a small flask featuring a saint and two crosses were found. 7

A source from literature adds information: The Muslim geographer and historian Abu-'l-Qasim Muhammad ibn Hawqal from the 10 th century describes in his geographical treaty The Representation of the Earth a Christian monastery which he visited around the year 970 as follows: “Al-Sawadar is a mountain to the south of Samarkand. On al-Sawadar there is a monastery of the Christians where they gather and have their cells. I found many Iraqi Christians there who migrated to the place because of its suitability, solitary location and healthy climate. Many Christians retreat to it, it towers over Sogdiana. It's called Wazkard“. 8

The Russian archaeologist Alexei Savchenko believes that “Wzkrd”, which is named “Wrkwd” in another manuscript, is nothing else than Urgut. His excavations from 1997 till 1999 brought an architectural complex with several rooms to light which may belong to a monastery. The radiocarbon dating of construction material suggests the 9 th century as the time of founding.9 Unfortunately, some road construction destroyed in 1995 the western and eastern edges of the complex. After 1999, financial constraints brought this promising project to a temporary standstill.

Relevance

Since most architectural relics of the Church of the East located to the east of Iran have been destroyed by wars and persecutions, the discovery of a Nestorian (or Syrian-Orthodox) monastery would be of high cultural importance. If one abstracts from the relatively numerous Christian gravestones found in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, China and Inner Mongolia, a few Chinese stelae as well as the few architectural remains in Kerala, South India, the only architectural relics from the Church of the East left are the foundations of a larger church complex, another church and a chapel in Ak-Beshim, Kyrgyzstan, of a presumed church in Termez, Uzbekistan,10 of a church in Kocho, Xinjiang, of a presumed Da Qin monastery near Wuchun, Shaanxi as well as of a hardly recognisable church in Olon Sume, Inner Mongolia – the three latter ones are in China. In the light of this rarity, the discovery of a Nestorian (or Syrian-Orthodox) monastery at Urgut would be of highest relevance.

Goals

The planned excavation campaign will try to locate the presumed church in order to prove the monastic nature of the complex. Also the nearby zone of burials is a target for prospecting.

| Project leader Dr. Alexei Savchenko Arabist and archaeologist Bekhterevsky per. 13, kv.9 04053 Kiev, Ukraine www.apple.kiev.ua/esarex |

On the name and location of the Christian settlement of Urgut by Dr. Alexei Savchenko ( |

In cooperation with:

The Archaeological Institute, Samarkand, Uzbekistan

_______________________________

3 Just based on these inscriptions it cannot yet be decided if they were written by members of the Church of the East or of the Syrian-Orthodox Church. The same comment applies to the ruins of the presumed monastery. However, based on the much larger spread of the Nestorian than the Jacobite Church in Sogdiana, the hypothesis of an Eastern Syriac monastery is more likely.

4 Tardieu Michel: Un site chrétien dans la Sogdiane des Sâmânides. In: Le Monde de la Bible,

No. 119. may - june 1999. p. 42.

5 Savchenko Alexei: Urgut Revisited. In: ARAM, Journal of the Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies, vol. 8: 1&2. Oxford-Harvard 1996. p. 334f. The Monastery of Urgut investigated by The East Sogdian Archaeological Expedition. ESAREX, 1999. p. 1. www.apple.kiev.ua/esarex

6 Klein Wassilios: Das nestorianische Christentum an den Handelswegen durch Kyrgyzstan bis zum 14. Jh. p. 226f.

Brepols, Turnhout 2000.

7 Paykova Aza Vladimirovna: The Syrian Ostracon from Panjikant. In: Le Muséon, Éditions Peeters, Leuven 92/1-2, 1979. p. 159-169. Savchenko Alexei: Urgut Revisited. In: ARAM, p. 339.

8 Ibn Hawqal: La Configuration de la Terre. Ca. 988. Introduction et traduction par J.H. Kramerd, G. Wiet. Maisonneuve & Larose, 2 vols. Paris 2001. p. 477f.

9 Savchenko Alexei: The Monastery of Urgut investigated. p. 5.

10Albaum, L.I.: Xristianskij xram v starom Termeze. In: Iz istorii drevnix kultovsrednej Azii. Xristianstvo. Glavnaja Redakciha Enciklopedii, Taskent 1994. p. 34-41.

Excavations 2004: Brief Report

This year, the East Sogdian Archaeological Expedition resumed excavations of the site of Sulayman-tepe, known to the older generation of the local inhabitants as Urus-Machit (“The Russian Mosque”). The works started on August, 16, and ended on September, 25 (six working weeks in total). The agricultural activities had previously resulted in some damage to the archaeology, the site having been partly bulldozed and holes and trenches dug for tree planting and irrigation, but despite this, the buildings and features have survived well enough.

The excavations of 2004 focussed on the area where the trench in 1999 had demonstrated the extensive preservation of walls and paved floors below the surface. The efforts were concentrated on the main site, in order to clarify the nature of the buildings, to retrieve dating material, and establish the plan of the settlement. In addition, it was also decided to excavate two wells on a plateau to the east of the main site. The excavations uncovered a sizeable section of a large and sophisticated architectural complex which may well have been monastic in nature. We date it provisionally to around AD IX to AD XIII on the basis of the pottery recovered. The architectural remains revealed at the main site provided a clear plan of several rooms and corridors. All premises were cleared down to their fine paved floors or rough dirt floors , appearing to be devoid of evidence for their function . The walls, which could have stood to a maximum of approximately 3 m, were in many places truncated or destroyed. They do not appear to have fallen in one piece; rather they fell in blocks over a perhaps lengthy period of time.

Several periods of occupation were identified, the earliest associated with the initial foundation of the complex, the later suggesting a re-occupation when the original structures suffered damage and were abandoned or destroyed. This ‘squatter' phase was represented by a small temporary hearth found embedded into the paved floor. The building materials used on the site are fired brick of several shapes ( 30 x 15 x 5 cm, 23 x 23 x 5 cm, 30 x 30 x 5 cm and 27 x 8 x 5 cm ), ceramic tiles 30 x 20 x 2,5 cm, used for flooring, and mud brick. Among rubble which appeared to have fallen from a wall, fragments of decorative plaster and remains of emerald-green, carmine, ochre, white and cobalt stucco were found.

One long-awaited result was the discovery of conclusive evidence of the Christian presence at the site. This evidence came in the form of a [wearable?] metal cross found in same context with a well-preserved oil lantern dating to XIII AD. This discovery supports our initial set of assumptions as regards the Christian presence in Urgut, which is now appearing in the archaeological record after remaining hidden for so long, complementing and expanding on the information provided by the historical texts.

The material found, also numismatic ones, are in the process of being analyzed. In the meantime, a guard has been appointed to ensure that the site remains undisturbed by outsiders.

Excavations in Urgut: August–October 2005

Progress Report

|

|

GIS by Dr E. Potapov, Univ. of Pennsylvania, eye alt. 8.51 km |

This year the research team continued excavations of the site of Sulayman-tepa, believed to have been the seat of the Christian monastery of Warkūda (present-day Urgut) in IX–XIII AD.1 The site with precise geographical coordinates: 39º22'46'' N, 67º14'28'' E, elevation 1134 m is situated at the southernmost edge of the habitable territory of the town of Urgut, Samarkand province, Republic of Uzbekistan.

The goal set for this season was to extend the excavations in the three available directions (north, east

and south) in order to uncover the perimeter walls and to excavate the previously pin-pointed room behind

the main northern wall.

|

Works in the S–E sector were obstructed by the huge planetree overhanging the dig and having its roots deep in the earth mass. The tree had to be removed as it was a danger to the people working around and could destroy some fine architectural elements had it suddenly fallen. Upon cutting down the tree, a dendrochronological examination of its trunk was done. The tree appeared to be 700-800 years old, which means that it grew here (or was intentionally planted) no great length of time after the decline of the settlement in XIII AD. This additional chronological evidence accords well with the terminus post quem so far established for the site on the basis of the ceramics, coins and radiocarbon analysis. |

1The background to the excavations is described in my papers: “Urgut Revisited”, ARAM Periodical (The Journal of the Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies, Oxford–Harvard) № 8 (1996); “По следам арабских географов” (In the Footsteps of Arabic Geographers), Археологические исследования в Украине (Archaeological Researches in Ukraine) № 7 (2003–2004), Kiev 2005; “По поводу христианского селения Ургут” (On the Christian Settlement of Urgut), Записки Восточного отделения Российского географического общества (Transactions of the Oriental Department of the Russian Archaeological Society) № 2 (XXVII), St. Petersburg 2006.

A group of plane-trees of the same age or older mark the mazar (holy grave) of Khoja Abu Talib Sarmast, one of the four missionaries who came to Urgut from Bukhara to propagate Islam in X AD. This mazar, known locally as Chor-Chinor ("Four Plane-Trees"), is situated near Sulayman-tepa, and a possible link might be established by further research. |

The tree shown here was 1050 years old at the time of the dating (1990s), as attested by the plate in the top left corner of the photo. Before 1920 there was a Muslim grammar school (maktab) inside the trunk.

After the loess sediments were removed, we were pleased to observe that the main eastern wall survived the destruction of 1996, being intact. This fact allows to analyse the space syntax of the complex in its entirety, greatly increasing the value of the results and the plausibility of the reconstruction. The main eastern wall was made of mud brick, a narrow stripe of outside premises paved with fired brick situated behind it. At least two building horizons are present. Some boulder stones that still remain in the vertical plane of the hill at various heights, as well as memories of the old inhabitants2 suggest that initially this slope had been converted into a sequence of terraces gradually lowering towards the east.

| Space behind the main eastern wall, looking north | Same space, looking south |

2 Of the informants I should pick out as the most knowledgeable and co-operative Warr. Off. Ret. Khursan-

Murad Ghaffarov, the present Guardian of Sulayman-tepa, and Timurlang Khalikov, 80-year-old healer, storyteller and keeper of the local lore.

In order to interpret the form and function of the excavated part of the building we shall now treat it together with the previously excavated sectors. There is an element of standardization which suggests a system at work that fits well with the order implicit in a monastic settlement, where uniformity of building would be a characteristic of the community. The overall layout of the complex can be conveniently described as two aisles separated by a raised platform in the centre. The walls of the platform were made of fired brick, forming a rectangular structure up to 25 rows of brick high in the better preserved wertern part. This perimeter was filled with clayey loess well rammed to the surface of the ground (a vertical stratigraphic shaft has been laid to check the uniformity of the filling). The fact that the purpose of the walls was to serve as a contour only is confirmed by the fact that no care has been taken to arrange bricks regularly inside, by contrast to the smooth line of brickwork on the outside.3

The top of the platform could be reached through the aperture in its western wall which must have been followed by a mud brick or loess stairway, not preserved. I believe that the most plausible interpretation of this platform is as of a bēma which played an important role in the liturgical setting of the Eastern Syrian churches and was situated in the centre of the nave (although the exact position varies). If this assumption is correct, then we have a quite rare example of an Eastern Syrian church with a well-preserved bema, since little archaeological material independently confirms its importance.4

3 “Inside” and “outside” relate here to the walls of the platform, which still is part of the interior of the building.

This means that the outside of the platform was seen by the visitors as the walls of the northern and southern

aisles and of the western corridor between them.

4 Of the recent studies v. Marica Cassis, ‘The Bema in the East Syriac Church In Light of New Archaeological

Evidence’, Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, Vol. 5, № 2 (July 2002), and the bibliography therein.

Northern aisle and chancel

The northern aisle starts with the main entrance in the western wall excavated in 1999 and continues eastwards, elevating by three steps before reaching the culmination point. The fine investigation revealed there a cross-shaped room recognisable as chancel, with the altar adjoining the eastern wall and constructed of fired brick. The seat of the priest who, in the tradition the Church of the East, was serving the liturgy facing the altar, is marked by ceramic tiles inserted into the flooring edgewise. The floor of this room is made of ceramic tiles plastered with a fine gypsum which is still intact over most of the church interior. Small fragments of stucco were found on the walls, adding colour carmine to the range already established: white, emerald-green, ochre and ultramarine. These traces of colouring are so slight that it is impossible to determine whether they are the remains of a single overall colouring or some more complex decoration.

Southern aisle and beyond

Another aisle, also extended along the axe W–E, is situated between the southern side of the platform and the main southern wall. The wall ca. 1,5 m thick was made of mud brick faced with several rows of fired brick on the inside. It has two doorways leading outside, one of which was intentionally filled with rubble and brick breakage. |

|

In the east the wall ends with a curving suggesting an apse; however, its clear delineation or just any fine investigation of this corner was complicated by the ubiquitous roots of the plane-tree which have greatly deformed all surrounding substance. The floor of the aisle is paved with fine quality ceramic tiles with traces of plaster finish in several places. In the east the floor elevates to form several footsteps leading outside the main eastern wall. At least one footstep was made using the common dandona technique, when the bricks are laid edgewise in order to increase wear resistance. It is on these footsteps that the iron cross was found during the last year’s field campaign.

Outside the main eastern wall were the remains of another premise, also under the roof judging from the gypsum plastering of the paved floor. In the centre of this room, exactly on the axis W–E stands a rectangular base made of fired brick. The location of this room and a decorative context in the form of a rounded niche filled with a ceramic plaque suggest its use as an oratorium external to the main nave. In the cross piece of the eastern wall between the central and the south-eastern sectors, in a niche, was found a glazed lantern full of substances which are likely to be oil. This is an excellent and rare case of obtaining sufficient amount of material for C14 sampling. The contents was passed to the Radiocarbon Dating Lab of St. Petersburg Institute of Archaeology where it will be examined by Dr Sergei Vartanian. |

|

| Decorated niche in the rear side of the main eastern wall. |

Northern yard

This space with an earthen floor, external to the main building, is linked to the northern aisle by two doorways in the main northern wall and one more narrow passage connecting it to the chancel. In the eastern end there is another rectangular stand made of fired brick. The room was not excavated at full length due to the lack of time; this is the direction in which the excavations will continue in the next season.

Finds

| Glasswork found in the bottom of the water reservoir connected by an underground tunnel to the mountain water stream. | Fragment of a stone lantern from the chancel. |

As there is a good reference collection of stratified ceramics for the area, there are no difficulties for the interpretation of our finds. The study of the pottery and glasswork from the excavated site suggests an early Samanide date for the founding and an early Mongol date for the end of the main occupational period (followed by the another with a squatter re-occupation after damage to the original structures).

While these preliminary observations may require amendment in the light of future excavation, there is enough evidence available at present to propose that the Sulayman-tepa assemblage indicates occupation between IX AD and XIII AD, and not extending far into the Mongol period. This accords well with the previously obtained C14 dates (one more process is pending).

The first evidence of a Christian element at the site came to light in 2004 when an iron cross was found on the steps in the eastern part of the southern aisle. More Christian artefacts, found in this season, should be included into this report:

| Fragment of a decorative tile from the nave. | Fragment of a plate with an offprint of a seal with a "Nestorian" cross. |

| Fragment of a ceramic plate kept in a niche. |

Parallels

While the full rationalisation will only be possible when all adjacent rooms are excavated, the most exact parallel to the site is provided by the church complex recently excavated in Aq-Beshim, Qirghizstan, and brought to scholarly notice by G. Semionov, Суяб. Ак-Бешим (Suyab. Ak-Beshim), St. Petersburg 2002, pp. 44-114.

Addenda

A moulded ceramic pot featuring a cross and an ornamental scribble resembling Syriac characters suddenly came to light this year, some 40 years after it had been unearthed in Urgut. It was kept at a private collection in Samarkand, where Mr Firdaws Naberayev of the Regional Inspectorate of the Antiquities noticed it and brought it to my attention. By an almost holmesiane inquiry I managed to establish that it was found in the late 60-ies by the now retired schoolteacher Juma Daniyorov, who with the help of his pupils once undertook amateur excavations of a tepa in his home village of Gus-Say, the western suburb of Urgut. Great is my indebtness and gratitude to the owners, Ms Kutbiya Rafiyeva and Ms Aziza Haydarova, who kindly agreed to give it as a free gift to the Samarkand Historical Museum when they realised its importance.5

| Pot for hallowed water of oil, VII-XI AD. | Quq-tepa in Gus-Say where it was found. |

In this season a vague semantic link has been tentatively established between the monastery and the inscriptions on the rock above it. While doing theodolite survey, we observed that the walls of the building, despite being very neatly erected, deviate from the magnetic axis by 15º. This is explained by the simple fact that, in the absence of a compass, the builders’ only reference points were those of sunrise and sunset. The rocks of the two mountain ranges – Qutirbuloq to the east and Gulbogh to the west – prevent the viewer from seeing the sun at horizon level (which would have more or less coincided with the geographical East of West). This fact means that the reference point shifts a number of degrees, as it takes the sun some time to move from the horizon to the point where it becomes visible above the hills.

It can now be stated with confidence that in the summer period (that is, when the building works should have been conducted), the sun rises at dawn exactly from behind the rock of Qizil-Qiya (“The Red Rock”), as opposed to any of the other rock in the Qutirbuloq gorge that are clearly visible from the site. Since I am unable to comment on this fact any further at this stage, I will leave it as is.

It would be appropriate to add here that two more inscriptions from this epigraphic site have been read and interpreted recently by Prof. N. Sims-Williams of SOAS, London, throwing light upon the monastery’s geographical connections. One of them (also showing a cross) consists in the word bxt “[good] fortune” in the Sogdian adaptation of the Syriac script (while the form is Persian); the other may be Turkish Alp (“hero”, personal name) in Uighur script.

5 The two refined ladies run a small private hotel in the historical centre of Samarkand which I would recommend to any short- or long-term visitor. 58 Iskandarov St. (just off the Gur-Emir Mausoleum), tel. 2352092, muhandis2004@rambler.ru May an increased flow of visitors be a reward for their co-operation.

Acknowledgements

This year, Dr Gennadiy Ivanov volunteered to take charge of the cameral work and to assist with the excavations. I have long known this archaeologist, formerly based in the Ferghana valley, as one of the country’s leading specialists in the field; however, we had met only briefly. Having spent two months together in the hills, I realised in full measure the scope of this scholar’s erudition, experience and insight. I can only regret that our acquaintance did not take place in the former years; I am comforting myself with the idea that the real investigation of the lost monastery is just starting.

Excavations in Urgut: June – July 2006

Progress Report

Timurlan Khalikov holding a 10 th century jar discovered at Urgut.

He helped identifying the location of the monastery.

A new field campaign at Sulayman-tepa in Urgut was conducted during May and June, 2006. This year, the excavations were concerned with the area to the north and south of the church building unearthed in the previous seasons. The aim was to complete the excavations of the northern nave, to uncover the outside edge of the main walls, and to improve the general plan. The northern nave was excavated down to the level of the beaten clay floor. The entrance from the western side appeared to had been filled with rubble, which probably indicates a squatter occupational period of the complex. Summarising the result, it can be safely argued that beyond the southern nave there lies an open yard with no architectural structures whatsoever; beyond the northern nave a habitational context was discovered consisting of a number of ovens ( tandoors ) and a cesspit ( badrab ), leaving us with the interpretation of this sector as a kitchen.

It is this context which provided us with the earliest dated find so far: a bronze coin of the Sogdian ruler ( ikhshid ) Turghar, 1 st quarter VIII AD (type “B” according to the accepted classification)1 . |

|

| Space in front of the entrance to the northern nave, facing north-east. |

| The new chronological evidence provided by this singular find is amplified by another artefact dating to the same period or earlier: fragment of a ceramic beaker being an imitation of a wooden prototype. While a fuller substantiation will only be possible after this sector is studied in its entirety, these finds throw new light upon the chronology of the complex, shifting its possible terminus ante quem back by a century. | |

The earliest firm evidence for the monastery was so far provided by the date in an inscription on the rock of Qizil-qiya, “August of the year 1206 [of Alexander]” = August 895 2. However, it would be natural to expect that the monastery was founded before the Arab conquests (around AD 712 for the district of Samarkand), since the Islamic restrictions on new church building are well-known.3

Still there were some exceptions from the general rule, e.g. legal church construction in Muslim Spain 4 or the foundation of the Monophysite Church of Mary Magdalene at Jerusalem, endowed by a notable of Alexandria in 820 5.

1 O. I. Smirnova, Svodniy katalog sogdiyskikh monet, Moskow: Nauka 1981, q. v.

2) M. Tardieu, ‘Un site chrétien dans la Sogdiane des Samanides’, Le monde de la Bible 119 (mai-juin 1999), p.

42.

3) See, e.g.: Abū Zakaryā Yahyā b. Sharaf al-Nawawī (AD 1233-1278), Al-minhaj bi-sharh Sahīh Muslim, English

translation in Bat Ye‘or, Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide, Fairleigh Dickinson University

Press 2002.

4) Sally Garen, ‘Santa María de Melque and Church Construction under Muslim Rule’, The Journal of the Society

of Architectural Historians, vol. 51 № 3 (September 1992), pp. 288-305.

5) Severus ibn al-Mukaffa‘, ‘History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria’, Patrologia Orientalis

Vol. 10.5, col. 460.

|

|

|

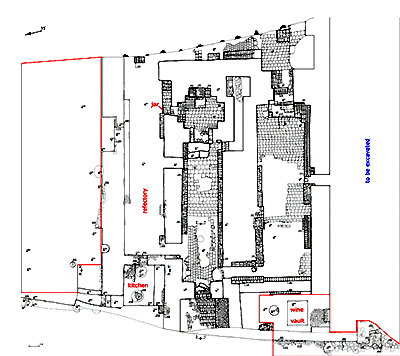

| The red line indicates the area excavated in 2006. |

The main problem presented by the ground plan is that of the prototypes. The cross-shaped chancel

terminating the nave finds its parallels in the following known examples:

Of the three ecclesiastical buildings known in Central Asia6 the same feature is present at the more recently excavated church in Aq-Beshim7.

6) see the detailed discussion in: A. Naymark, Sogdiana, Its Christians and Byzantium: A Study of Artistic and Cultural Connections in Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages , unpublished PhD thesis, Univ. of Indiana 2001.

7) G. Semenov, Suyab. Ak-Beshim , St. Petersburg 2002, figs. 2, 4, and 27.

In the light of the above-listed parallels I would cautiously highlight the fact that Mt Allahyarhan , “the mount of the zealots”, at the foothills of which the monastery was situated, shares its semantic core with Tur ‘Abdin , “the mount of the servants [of God]”.

8) J.-M. Fiey, ‘Proto-histoire chrétienne du Hakkari turc', L'Orient Syrien 9 (1969), pp. 443-72.

Faith Carved on the Rocks

In this season, a number of previously unknown Syriac inscriptions were found, sought after since our first surveys of Urgut in 1995.

This story began in 1955 when a group of schoolchildren led by geography teacher and a scout came across a cave cemetery in the gorge of Gulbogh which also appeared to be an epigraphic site.

|

|

|

| The hill of Bobo-Qurboni (“Granddad’s Belly”), view from the site of Sulayman-tepa. On the left and behind is the mountain of Allahyaran, on the right – the gorge of Gulbogh. |

|

|

|

| View looking out from a one-time hermit’s cell | ‘Abdisho (“servant of Jesus”, personal name) |

An account was published in a regional youth newspaper,.9 to become the starting point of our longlasting investigations which yielded their result only now.

Inside the caves was noticed the presence of Shilajit (Mumiyo), blackish-brown exudation used in popular medicine,10 and plants of the genus Eremurus.11 Both substances have healing properties, which suggests a link with strong medicinal traditions at Syrian monasteries which often comprised a hospital.

More than 60 varieties are known

across Eurasia, from Afghanistan

to the Caucasus: Eremurus sogdianus,

bucharicus, hissaricus,

nuratavicus, tianschanicus, turkestanicus,

tadshikorum , etc. The leaves are taken as a fresh salad, while the roots are used for the preparation of glue applied in bookbinding and shoemaking. The same glue was also added to the grout for extra stickiness. In the popular medicine the pounded roots were used for treatment of abscess and tumour. Craftsmen were also using this plant to dye wool and silk into colours pink, yellow and olive. |

|

|

|

| Drawing of what can be interpreted as a church tower on the wall of cave 2. |

|

9) The text is available in my translation from Uzbek in: Alexei Savchenko, ‘Urgut Revisited', ARAM Periodical

8 (1996), pp. 341-32.

10) A Syriac etymology of Mumiyo is proposed by Dr Rainer Nabielek of Freie Universität Berlin in his Heilen

mit Mumia (Mumia naturalis) . Herkunft und Geschichte eines jahrtausendealten Allheilmittels , forthcoming.

11) T. Konovalova, Eremurusy , Moscow: Armada-press 2001.

Beyond Urgut

A survey of the site of Quq-tepa in Gus, west of Urgut, was conducted. In the light of the archaeological evidence the preliminary identification of this settlement is that of a hamlet or a secluded par-ish.12 An acquisition was made to the benefit of the Historical Museum in Samarkand. This wearable cross was purchased from a private owner and given as a gift to the Museum where it is now exhibited together with the rest of Christian finds from the Samarkand region. |

|

12) v. Alexei Savchenko, ‘Urgut', Encyclopaedia Iranica (www.iranica.com), forthcoming.

We owe our thanks to the following persons and institutions directly involved in the described Sergei Rovensky, communications technician, Samarkand Airport; Michael Jouravlev, lab assistant, ESAREX; Sattar Ghaffarov, field assistant, ESAREX and resident, mahalla (community) of Chor-Chinor, Upper Urgut – for discovering the cave hermitage; Samarkand Regional Inspectorate of the Antiquities – for taking every effort to safeguard the results of our work; Timurlan Khalikov (Timur-bobo, v. photo on the title page) – for the efficiency of his prophecies.

The East Sogdian Archaeological Expedition, from left to right: Samariddin Mustafakulov, archaeologist and anthropologist; Olga Jouravleva, architect; Gennadiy Ivanov, archaeologist and topograph-er; Alexei Savchenko, archaeologist and Orientalist. |

|

***

Excavations in Urgut

June – July 2007

Progress Report

Sign board at the archaeological site

In June, 2007 the team continued excavations of Sulayman-tepa, the seat of the monastery of Urgut (Warkudah).

Initially the works concentrated beyond the main northern wall of the northern aisle. That is the sector where an habitational context was found during the previous campaign, in the form of a cooking place provided with several ovens (tandoors) and a cesspit (badrab). That was the long-awaited evidence of household activity of the monastery’s inhabitants.

In the course of the first two weeks the area of ca. 100 m2 was excavated, to reveal no presence of architectural structures or significant artefacts. It became clear that the northern aisle was the last room belonging to the church complex, and the area to the north of it was void of material remains except insignificant.

|

|

|

| North-western sector of the dig beyond the last northern wall, facing N-E. |

In the light of this fact the nature of the northern aisle became more clear. On one hand, it has all the features of other two naves: same proportions and the altar-like structure in the eastern end. On the other hand, it lacks the rest of the architectural details – the steps and the narrowing (skakona) separating the chancel from the naos, the paved floor, or the decorations. Moreover, it is contiguous to a kitchen situated where the main nave has narthex – immediately before the entrance to the hall from outside.

Upon consideration we decided to identify it as a refectory which was considered to be a sacred place in some Eastern monasteries, and even in some cases was constructed as a full church with altar, where some services were specifically performed. All food served in the refectory should be blessed, and for that purpose, holy water was kept in the large pot found in one corner.

At this point the works were relocated to the southern sector where we continued to investigate the space beyond the main southern wall and to the west from it.

In the S-W sector, at floor level was found rectangular brickwork, at first glance resembling a funeral decoration. Upon removing, the surface structure gave way to a sealing made of large pieces of shale which once were solid slabs. Further down, at depth. 1,5 m were found remains of a large ceramic vessel dug into the ground. The bottom and the inside walls of the jar were covered with whitewash, with clear traces of claret-coloured depositions on it.

|

|

|

|

| Phases of the excavation of the wine cellar in the south-western sector of the site. | |

|

|

Given the peculiar colour, it is most likely that the depositions were produced by must or wine. Putting Calcium hydroxide into wine is a centuries-old technique used to prevent the product from going sour by neutralising extra acid. The purpose to which the vessel had been put is thus clear: it is a wine jar, and the context in question is a wine cellar.1

Christian wine-making is attested at three other sites in Central Asia:

– winery in the monastery of Aq-Beshim (Suyab) in Qirghizstan;2

– jar with a Sogdian inscription containing a Syriacism (malpna – teacher or doctor) found at the site of Krasnaya Rechka in Qirghizstan;3

– bottom of a tub laid with bricks with carved crosses, found at a winepress in Aq-Tobe (Southern Kazakhstan).4

It should be said at this point that impressions of a stamp on several pottery items from Urgut are identical to those found in Aq-Beshim, Novopokrovka (Qirghizstan), and Krasna-ya Rechka (this last accompanied by the name of “craftsman Pastun”).5

On the top of the roof of the cellar was found a sealed pottery assemblage consisting of unbroken items and items that can be put together from fragments. Such assemblages usually belong to the time of destruction of an archaeological complex and testify to a sud-den and abrupt death of a monument.6

|

|

1 Close semantic link between Christianity and wine-making is illustrated by the following passage by the Arab lexicographer al-Firuzabadi (AD XIV): “Mushammas is a name for wine. It is derived from shamms, the name given to the deacon of a Christian church and it means: a wine grown and nursed by a shamms” . – v. D. S. Rice, ‘Deacon or Drink: Some Paintings from Samarra Re-Examined’, Arabica 5 (1958), p. 22.

2 G. L. Semënov, Raskopki 1996-1998 gg., ‘Suyab. Ak-Beshim’, SPb. 2002, pp. 44-114. V. also: G. L. Semënov, ‘Mona-styrskoye vino Semirechya’, B. B. Piotrovsky Memorial Readings at the Hermitage, SPb. 1999, pp. 70-74.

3 A. N. Bernshtam, ‘Uygurskaya epigrafika Semirechya’, Epigrafika Vostoka 1 (1 947), pp. 34-37.

4 K. M. Baypakov, Srednevekovaya gorodskaya kul’tura Yuzhnogo Kazakhstsna i Semirechya, Alma-Ata 1986, p. 184.

5 V. A. Livshits, ‘Sogdiytsy v Semirechye: lingvisticheskiye I epigraficheskiye svidetel’stva’, Pis’menniye pamiat-niki I problemy istorii kul’tury narodov Vostoka. XV yearly conference at Leningrad Dept., The Institute for Oriental Stu-dies, December 1979, part I (2), Moscow 1981, p. 80.

6 V., e. g. V. I. Raspopova, Zhilishcha Pendzhikenta, Leningrad 1990, p. 17.

Since there is a good collection of stratified ceramics from the area, the complex found can be safely dated to the early XIII century, thus providing the terimus post quem for the mona-stery which probably corresponds to the Mongol taking of Samarkand in 1220.

A number of fine cleanings was undertaken in order to establish and mark on the ground plan the main western wall destroyed by a seasonal mountain torrent between 1999 and 2004, yet before we were able to study the corresponding sector.

|

|

|

| Western slope of Sulayman-tepa in 1997 with the brickwork of the western wall clearly visible. | |

Apart from the excavations of the main site, we continued to map other local spots where Christian presence was attested in some way or another. The following sites were surveyed:

– Durmon-tepa in ca. 20 km to the west of Samarkand, where a mediaeval Christian burial was found in 1986, containing a cross of sheet gold. The cross had been sewn onto the dress of the dead, which probably indicated his priestly rank;7

– Arbinjan-tepa in ca. 80 km to the west of Samarkand, on the road Samarkand-Bukhara which once was a major trade route. Ceramic cast for moulding crosses was occasionally found there several years ago;8

– Kosh-tepa 2 in ca. 10 km from Urgut, where a rim of a jar featuring a scratched scene of baptism was found in 1973;9

– the area where a bronze cross was found in 2006 appeared to be flooded by the Chimkur gan water reservoir (ca. 70 km south of Samarkand).

– an area near Chinaz, Tashkent province was surveyed in order to pin-point the site of the other of the two Christian settlements in Mawarannahr described by Arab geographers (described separately, v. Addenda).

7 G. V. Shishkina, ‘Netorianskoye pogrebeniye v Sogde Samarkandskom’, Iz istorii drevnikh kul’tov Sredney Azii. Khristianstvo, Tashkent 1994, pp. 56-63. The item is kept at the Museum of the Peoples of the Orient in Moscow.

8 kept at the Institute of Archaeology in Samarkand.

9 M. M. Iskhakov, Sh. S. Tashkhodzhaev, T. K. Khodzhayov, ‘Raskopki Koshtepa’, Istoriya material'noy kul’tury Uzbekistana 13 (1977), pp. 88-97. Current location unknown.

| Main part of Durmon-tepa, facing north. | Arbinjan-tepa watered by the river Narpay, facing south-east. lt was the main centre of the resistance to the Arab conquest, and the last ruler of Sogd Divashtich was executed here |

|

|

| Kosh-tepa 2, now Iargely destroyed, looking south-east. | |

|

|

| The cast from Arbinjan-tepa. | Gravestone accidentally discovered in Panjikant, Tajikistan, most probably of Semirechye origin. |

Permanent stainless steel big board was mounted at Sulayman-tepa explaining the significance of it and warning visitors against misconduct.

Twelve previously unknown archaeological sites dating to the early Middle Ages were dis-covered and mapped in the course of our surveys of the Urgut area.

Alexei Savchenko

Director of Research,

The East Sogdian Archaeological Expedition.

Conclusion of the excavation project at Urgut

After careful considerations it has been decided by the project leader Dr. Alexei Savchenko and the Society for the Exploration of EurAsia to conclude the fieldwork at Urgut since the project's objective set in early 2004 has been fully achieved with the discovery and excavation of the Christian church and monastery belonging to the Church of the East mentioned by the 10 th century geographer and historian Ibn Hawqal.

The results from this project will be published in scientific and popular media in due course which will be mentioned and possibly also published on the Society's homepage.-

Alexei Savchenko, Mark Dickens: Prester John’s Realm: New Light

on Christianity between Merv and Turfan. In: Erica Hunter

(ed.): The Christian Heritage of Iraq, Gorgias Press, 2009 (.pdf).

- Alexei

Savchenko: Östliche Urkirche in Usbekistan. In: Antike Welt, Philipp

von Zabern, Mainz, 2/2010

(.pdf).

| copyright by The Society for the Exploration

of EurAsia| E-mail

| Home

| ![]()

_klein.jpg)